Public Comments: December 2010 Personal Health Records and online advertising

-

Download the comments (PDF)

-

or Read comments below

—–

Comments of the World Privacy Forum

To the Department of Health and Human Services, PHR Roundtable: Personal Health Records, Understanding the Evolving Landscape

December 10, 2010

Via the web at http://healthit.hhs.gov/portal/server.pt/community/healthit_hhs_gov__personal_health_records_–_phr_roundtable/3169

1. Privacy and Security and Emerging Technologies

1. What privacy and security risks, concerns, and benefits arise from the current state and emerging business models of PHRs and related emerging technologies built around the collection and use of consumer health information, including mobile technologies and social networking?

The biggest threat to privacy comes from commercial, advertising-supported PHR vendors. This category includes any PHR provider or other provider of health information or health information services to individuals. A commercial, advertising-supported PHR vendor serves advertising that directly or indirectly discloses any specific health information about the user. It does not matter if a user’s information is 1) transferred directly to an advertiser through criteria established by the advertiser for ad placement (e.g., show this ad only to diabetics with good health plans, household income over $75,000 per year, and children at home); 2) obtained through search requests shared when search engine links are clicked; or 3) in any other manner. The result is the same for any transfer of information from or about the user to a third party. At the end of the activity, information about a user comes under the control of a third party who typically has no formal relationship with the user and who probably has no legal obligation to provide privacy protection. Any information that is transferred can be retained indefinitely by the third party and used without limitation. Even if the third party has a privacy policy that provides some degree of protection, the actual level of protection is unpredictable since nearly all privacy policies are subject to change without notice or consent.

Commercial, advertising-supported PHRs succeed by selling advertising, and advertisers want access to individual with known medical diagnoses, treatments, and interests. A commercial, advertising supported PHR is a service that profits by finding ways to transfer a user’s health information to an advertiser. The fundamental business model is one of the intent to convey information to advertisers; that the specific data in the case of a PHR is related to medical conditions does not change the fundamental structure of facilitating advertising. The most likely purchasers of consumer health information are pharmaceutical manufacturers who sell high- priced, patent-protected drugs. [1] These manufacturers do not know who their customers are, and they are willing to spend significant amounts of money to identify or contact the users of their products, including using social media. [2] The pharmaceutical/healthcare sector was expected to spend $1 billion in online advertising in 2010. [3] The information the manufacturers collect and maintain is not subject to HIPAA or any other known privacy law. The information can be retained indefinitely, used without limit, combined with other commercially available data, and sold or transferred to anyone without consumer notice or consent. By definition, none of HIPAA’s ban on use or disclosure of patient information for marketing applies to PHRs and others who are not HIPAA-covered entities. There is more information on these activities in the World Privacy Forum report on Personal Health Records: Why Many PHRs Threaten Privacy, available at https://www.worldprivacyforum.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/04/WPF_PHR_02_20_2008fs.pdf. We reproduce here from that report significant consequences of PHRs that are not subject to HIPAA:

• Health records in a PHR may lose their privileged status.

• PHR records can be more easily subpoenaed by a third party than health records covered under HIPAA.

• Identifiable health information may leak out of a PHR into the marketing system or to commercial data brokers.

• In some cases, the information in a non-HIPAA covered PHR may be sold, rented, or otherwise shared.

• It may be easier for consumers to accidentally or casually authorize the sharing of records in a PHR.

• Consumers may think they have more control over the disclosure of PHR records than they actually do.

• The linkage of PHR records from different sources may be embarrassing, cause family problems, or have other unexpected consequences.

• Privacy protections offered by PHR vendors may be weaker than consumers expect and may be subject to change without notice or consumer consent.

Any emerging technology that involves the sharing of information about individual consumers (or their families) may present the same privacy threats as non-HIPAA PHRs. Much depends on the nature of the technology, what information it collects, its privacy policy and terms of service, whether it is subject to any other privacy law, and other factors. It is possible for a service that collects and maintains a consumer’s health information to do so with a reasonable degree of protection for privacy, but there is no guarantee outside the law.

Those who track consumers online and who build dossiers of individuals can maintain enormous amounts of personal information and can keep that information for a lifetime. [4] Indeed, a consumer dossier can include information on an individual’s relatives so that information on a consumer may continue to be used to track individuals through multiple generations. Health information obtained by a consumer dossier company about a consumer may become immortal, retaining a value to the dossier company as along as a descendant or relative of that consumer is alive. The long-term value of health information through many generations may justify a larger investment to collect the information in the first place because of the likely stream of income that may result from the perpetual sale and resale of the information. The increasing availability of genetic information will only make these trends worse from a privacy perspective.

There is no guarantee that widespread commercial use of consumer health information for commercial purposes will produce better health outcomes or lower costs. Direct to consumer pharmaceutical advertising will continue as long as revenues increase. Health outcomes are not relevant to decisions about drug advertising. And because only high-priced, patent-protected drugs will be advertised, it is virtually assured that health care costs will increase whether or not outcomes improve. [5] As long as advertising produces net positive revenues, the motivation for the advertising will remain. Even those who are indifferent to privacy should worry because of the burden placed on health expenditures.

2. Consumer Expectations about Collection and Use of Health Information

Are there commonly understood or recognized consumer expectations and attitudes about the collection and use of their health information when they participate in PHRs and related technologies? Is there empirical data that allows us reliably to measure any such consumer expectations? What, if any, legal protections do consumers expect apply to their personal health information when they conduct online searches, respond to surveys or quizzes, seek medical advice online, participate in chat groups or health networks, or otherwise? How determinative should consumer expectations be in developing policies about privacy and security?

Consumers think that their health information is confidential and protected by law. They do not understand the limits on confidentiality imposed by HIPAA’s expansive authority to disclose patient records without consent. They do not distinguish between health records maintained by HIPAA-covered entities on the one hand, and the same information held by entities not subject to HIPAA on the other hand. Even smart people who are familiar with HIPAA have little idea about its scope. Most people do not know that if they allow their records to be held by a non- covered entity PHR, that record has no legal protections for privacy in the hands of the PHR vendor. When the World Privacy Forum released its report on PHRs and privacy in 2008, the most common reaction was surprise that HIPAA did not cover all PHRs. Reporters who cover health privacy issues and who are knowledgeable about HIPAA were not aware of the lack of privacy protections for most PHRs.

Consumers also have no basic understanding of the extent of privacy protections on the Internet. Most consumers think that if a website has a privacy policy, it means that their personal information cannot be shared with anyone. [6] Consumers reach that conclusion from the existence of a privacy policy. The actual consent of the policy – even if it says that consumer information can be shared – makes little difference to consumer beliefs. Consumers have no understanding of the extent to which their web surfing activities are monitored, tracked, recorded, and tied to them in a directly or indirectly identifiable way.

In short, consumers generally think that their health information has the same legal protection wherever it is maintained and regardless of who maintains it. With respect to online searches, quizzes, and the like, consumers have no idea that the health information they disclose is likely to be kept, tied to their identities, maintained indefinitely, unprotected by any privacy law, added to their personal or household profiles, and used to target advertising. Consumers are largely unaware of the privacy consequences of any online advertising.

Should consumer expectations determine policy here? There is no simple answer. Consumers are often poorly informed about law, policies, and practices that affect them directly. Many companies exploit consumer ignorance to make a profit. Recent changes to credit card and banking practices provide numerous examples. Consumers who did not understand overdraft charges for checking accounts paid billions of dollars in fees to banks. The new legislation makes it much harder for banks to exploit their customers through overdraft fees and in other ways.

When does a lack of consumer understanding provide a justification for a rule that bans an exploitive activity that consumers find it hard to avoid? When is consumer education a better approach? In the health privacy arena, we have had nearly a decade of experience with HIPAA, and consumer understanding is still at a low level. Frankly, understanding by health care providers is still at too low a level. Education may be a necessary response, but it will not solve the problem and is not sufficient to protect consumers against themselves and against those who will exploit loopholes and consumer ignorance to make a profit.

The problem goes well beyond consumer expectations any way. A good example is the doctor- patient evidentiary privilege. Consumers (and providers!) have some minimal knowledge about the existence of a privilege, but few who are not lawyers understand its scope. Virtually no consumer is likely to understand that the privilege may vanish if the consumer agrees to the transfer of a health record to a third party (e.g., a PHR vendor). It is not practical or possible to teach consumers the nuances of the law of privilege. If society wants to allow and encourage PHRs, then there will need to be legal protection for the records. Otherwise, the establishment of PHRs for consumers risks the end of the privilege. So this example shows that legal changes are needed when consumer expectations do not reflect reality.

3. Privacy and Security Requirements for Non-Covered Entities

What are the pros and cons of applying different privacy and security requirements to non- covered entities, including PHRs, mobile technologies, and social networking?

It is a necessity that different rules apply to covered entities and non-covered entities. The HIPAA privacy rule was specifically designed to cover health care providers and health plans. The rule recognized the needs and the contexts for providers and plans and allowed them considerable flexibility in the use and disclosure of health information. Whether HIPAA struck the right balances or not, the same needs and the same contexts do not exist elsewhere. Different circumstances call for different results.

The HIPAA privacy rules also made quite a few mistakes. For example, including health care clearinghouses (an institution that few consumers or even health care providers ever heard about) within the HIPAA privacy rule was a mistake. Clearinghouses do not need the same authority and flexibility that providers and plans require. To pick another example, the HIPAA privacy rule allows for disclosures to law enforcement and to national security agencies with either non- existent or inadequate procedural protections for individuals. This is not the place to argue that the HIPAA privacy rule’s disclosure provisions need to be narrowed. But it is the place to argue forcefully that some policies in the current rule should not automatically be extended to other institutions for which the rules were not designed.

A commercial PHR vendor seeking to make a profit or a social networking site that offers health services primarily to support advertising does not require any of the flexibility afforded providers and plans. There is simply no reason why a PHR vendor should be allowed to report identifiable information about communicable diseases to a public health agency. The obligation falls properly on providers. There is no reason for PHRs to disclose information for health oversight. Records needed for those purposes must and should come from providers and plans. There is no reason for PHRs to share information about military personnel. There is no reason for PHRs to share information with employers undertaking workplace surveillance in the workplace.

There are other disclosures that PHRs cannot avoid. Like any other record keeper, PHRs may receive a subpoena requiring disclosure of an individual’s record. Here, the HIPAA rule’s innovative requirement that the subject of a record covered by a subpoena must receive notice and an opportunity to contest the subpoena should apply to PHRs. A statute is needed to impose a patient notice obligation on those who use subpoenas to obtain records from PHR vendors. Researchers may also have reason to seek records from PHR vendors. There is more to debate here (e.g., whether patients should have a greater right to decide if their PHR records should be available for research), but when researchers obtain records from PHRs, the HIPAA standard for research disclosures (e.g., approval by an IRB) should be mandated.

Some HIPAA disclosure models will not work for PHRs. Law enforcement may have justification for obtaining records from PHR vendors. There is no reason to allow law enforcement to obtain PHR records using the same easy, warrantless, and paperless methods that HIPAA allows. A much tighter set of procedures is needs for law enforcement access.

Disclosures for victims of abuse, neglect, or domestic violence need to be reconsidered in a PHR context. Whether these disclosure obligations fall on PHRs under state reporting laws is likely to be a complicated question. When health records are maintained electronically and without any review by providers or other individuals, reporting obligations may not exist or may not be meaningful. However, if PHRs have reporting obligations, then most of the HIPAA requirements will make sense with some adjustments.

Each allowable disclosure under the HIPAA privacy rule must be considered in the PHR context. Many disclosures should not be allowed at all or should be allowed only with express patient consent granted in writing with full notice within the 30 days prior to the disclosure. Other disclosures should be allowed only if the standards and procedures required under HIPAA are narrowed. Some disclosures should not be allowed at all. The HIPAA disclosure modules are a starting point for regulation of PHR disclosures.

Other provisions of HIPAA may not make sense in a PHR context. Patient access to records should be unlimited. There will be no one in the PHR process who has an interest in reviewing patient records for information that is currently not accessible by the patient under HIPAA. Indeed, with electronic records generally – and particularly with records that will flow automatically to PHRs – the exemptions from patient access currently in the HIPAA rule will no longer work. Without a provider to serve as a gatekeeper and to make determinations whether patient access can be denied, all electronic records should be accessible to patients without limit. For the most part, this is an appropriate result. Indeed, as records become increasingly electronic and flow to PHRs, to other providers and plans, and to other third parties, limits on patient access to their own records will be unenforceable even in a HIPAA context.

Amendments to health records are troublesome under HIPAA. Many records are inappropriately exempt from patient requests for amendment. These limits will be unworkable in a PHR context. Whether patient amendment are allowed or not allowed, there will be conflicts with reasonable goals. If patients can change their PHR records as they see fit, the records may become useless to some or all users. For example, a physician may find it difficult to use a record that may have been altered by a patient. However, if patients cannot change records supposedly in their control in a PHR, then the rights of patients are undermined and the purpose of patient control of his or her own records becomes meaningless. The conflicts here are difficult and will not be easily resolved. Whatever choice is made will undermine, in some way, the value of PHRs.

The maintenance of duplicate health records by health care providers and by patients will present a series of issues and conflicts. Secondary users of health records that find HIPAA rules limiting and covered entities uncooperative may flock to PHRs, where vendors will be willing to disclose records for a price and patients can be more easily convinced to agree to disclosures that are not in the patients’ best interest. Legislative limits on PHR records and on other comparable records outside the HIPAA framework will be needed. There will be conflicts among disparate goals, and the tradeoffs will not be easy to resolve.

4. Any Other Comments on PHRs and Non-Covered Entities

Do you have other comments or concerns regarding PHRs and other non-covered entities?

a. Commercial activities, and in particular advertising and marketing activities, will undermine any privacy protections desired for health records. It will be too easy for a PHR vendor or another website to provide a link that a user can click on that will transfer an entire health record to a third party without meaningful consumer education on the potential consequences or the shift in legal protections from HIPAA-covered to non-HIPAA covered (when applicable.) Alternately, users may be asked to share medical information via web forms.

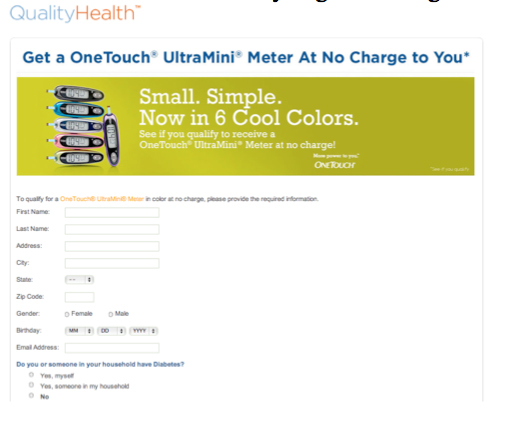

A great deal of this sort of activity already exists online, for example, health device manufacturers have already begun offering free devices online in exchange for information. [7]

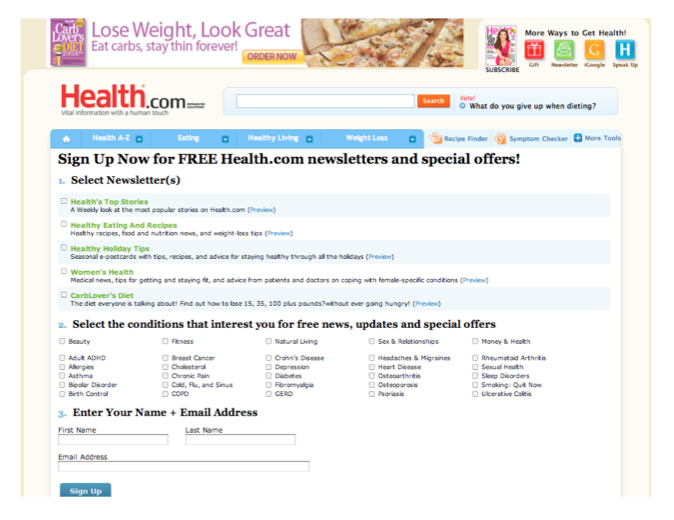

Other web sites request sign ups for more information, see the Health.com pitch below, meanwhile, privacy policies may state that this information can be shared for marketing purposes. [8] The Health.com privacy policy states, for example, “We may combine information we receive with outside records and share such information with third parties to enhance our ability to market to you those products or services that may be of interest to you.” We believe that few consumers who have indicated their health interests and given their name and email address have read the full privacy policy. [9]

The HIPAA rule prevents covered entities from engaging in this type of tactic. Without legislation, nothing will prevent non-covered entities, like PHR vendors and others, from engaging in the same tactics. Notices can be even less revealing that the example above. Any website can bury its disclosure practices in the website’s terms of service, knowing that few consumers will read or understand it. [10]

b. There is already abuse of the HIPAA by some websites that claim to be HIPAA Compliant. [11] Anyone other than a covered entity that claims HIPAA Compliance is engaging in a practice that is both unfair and misleading. Legislation may be needed to prevent misuse of claims or implications about HIPAA compliance. No one other than a HIPAA covered entity should be able to say that it is HIPAA compliant or is HIPAA covered.

c. Some aspects of PHRs will require new procedures and rules. For example, if we assume a robust marketplace for PHRs in the future, then patients may be presented with regular opportunities to select a PHR vendor in the same way that they are solicited to move their bank accounts to a new bank. Over the course of a decade, a consumer may change doctors, health plans, residences, and jobs. Each of these changes may result in a decision to use a different PHR vendor. Without clearly defined rules about maintenance of records by PHR vendors, an individual may find that his or her records are stored – incompletely – by multiple PHR vendors, some of whom no longer have a relationship with the individual. This foreseeable proliferation of health records needs attention and rules.

d. PHRs are an example of a cloud computing service. While the health privacy consequences of PHRs have been partially discussed in these comment, there are a host of other privacy concerns that arise with any cloud computing service, regardless of the nature of the records that the cloud provider maintains. The World Privacy Forum issued a report on the subject in 2009. Privacy in the Clouds: Risks to Privacy and Confidentiality from Cloud Computing is available at https://www.worldprivacyforum.org/2009/02/report-privacy-in-the-clouds/. We recommend the report for review by ONC. The report addresses the privacy consequence of third party storage of personal information; jurisdictional and legal issues that result from the storage of information in multiple jurisdiction; ownership issues; effects of bankruptcy of cloud providers; security and audit issues; and more.

_________________________________________

Endnotes

[1] For insight into state-of-the-art pharmaceutical marketing, see the agenda for the 4th Annual Digital Pharma East conference, October 2010, which includes sessions on such topics as “Six Steps to Becoming a Social Brand,” “Understanding the Power of Fan Culture in Healthcare Marketing,” “How Smart Is Your Phone: Leveraging Smartphones To Help With Patient Adherence,” and “Engaging Physicians Through Online Social Media to Ensure Use and Interaction.” 4th Annual Digital Pharma East Agenda, http://www.exlpharma.com/event-agenda/409. The e-Patient Connections 2010 conference, scheduled for late September 2010, offers a similar overview of contemporary health marketing, where companies can learn how:

- Novartis created a fictitious character and tapped the power of story-telling to reach those with cystic fibrosis

- Auxilium leverages the power of patient ambassadors

- Johnson & Johnson manages pharma’s largest YouTube channel and moderates comments

- Lundbeck uses social media to support rare disease communities

- Gilead use “Levels of Evidence” to measure and optimize their video marketing

- iGuard crafted a unique partner model to get over 2 million members in their program

LIVESTRONG manages their 900,000 Facebook page members.

e-Patient Connections 2010, Pharma Marketing News, 22 July 2010, http://campaign.constantcontact.com/render?v=001hgLWFIFcpZ0BENJNkIu1Movp- B3humakFfiYsZJqrzpiXkfEJRKyTGDCjmwkUHlY4xSv919ke8o3pYrDBNmuqkFQhiWEhEqnzkOmA7irKH0Hg H9Lt8aeXJ1WvKUQOXrZYvHt_HtdtjO0pA_NDpz9q0BkPYiVBfok4hMn2rd8Iviqzm0z8KajHH5ROGNMI7kQV Gh2Scbk6M0gMpLWvlvY5e2__W7PmIm1Lsba3s8wN8YrBAAdcO2zwWtDigIsWf3qAd7mtsWMKz_ybI3V8Eft gA%3D%3D#_jmp0_ (both viewed 9 Sept. 2010).

[2] For lists of pharmaceutical and healthcare social media efforts (covering brand-sponsored patient communities, non-brand-controlled patient communities, Healthcare Professional communities, Facebook pages and apps, YouTube pages and videos, Twitter pages, blogs, MySpace pages, Wikis, and miscellaneous Web 2.0 tools and sources), see Dose of Digital Pharma and Healthcare Social Media Wiki, http://www.doseofdigital.com/healthcare- pharma-social-media-wiki/ (viewed 30 Sept. 2010).

[3] eMarketer, “Pharma Industry Ups Digital Ad Spending,” 26 Aug. 2010, http://www.marketwire.com/press- release/Pharma-Industry-Ups-Digital-Ad-Spending-1310194.htm. According to OMMA data, the top 50 digital advertisers include Pfizer (#22), Johnson & Johnson (#24), AstraZeneca (#29), and Shire Pharmaceuticals Group (#38). “Top 50 Digital Advertisers,” OMMA Magazine, 1 July 2010, http://www.mediapost.com/publications/?fa=Articles.showArticle&art_aid=131889. OMMA Awards finalists for 2010 in the “Health, Wellness” category include Claritin, Botox Severe Sweating, and Practice Fusion’s Free, Web- based Electronic Health Records. OMMA Awards, http://www.mediapost.com/events/?/showID/OMMAAwards.10.NYC/fa/e.awardVoting/itemID/1416/voting.html (all viewed 30 Sept. 2010).

[4] See the testimony of Pam Dixon, World Privacy Forum, The Modern Permanent Record and Consumer Impacts from the Offline and Online Collection of Consumer Information before the Subcommittee on Communications, Technology, and the Internet and the Subcommittee on Commerce, Trade and Consumer Protection of the House Committee on Energy and Commerce November 19, 2009. < https://www.worldprivacyforum.org/pdf/TestimonyofPamDixonfs.pdf>.

[5] “DTCA has the demonstrated potential to drive medically inappropriate use. This may be particularly true of ‘reminder ads,’ which mention a product, but not an indication.” Comments of The Prescription Project, Community Catalyst and Prescription Access Litigation, Community Catalyst, Concerning Limitations and Risks of Direct-to- Consumer Advertising, Docket No. FDA-2008-N-0226, September 26, 2008,” http://www.prescriptionproject.org/tools/initiatives_resources/files/0011-1.pdf (viewed 30 Sept. 2010).

[6] See, for example, a Carnegie-Mellon study on behaviorally targeted online ads. This study found that “many participants have a poor understanding of how Internet advertising works, do not understand the use of first-party cookies, let alone third-party cookies, did not realize that behavioral advertising already takes place, believe that their actions online are completely anonymous unless they are logged into a website, and believe that there are legal protections that prohibit companies from sharing information they collect online.” Aleecia M. McDonald and Lorrie Faith Cranor, Carneigie Mellon University, An Empirical Study of How People Perceive Online Behavioral Advertising, Nov. 10, 2009.

[7] QualityHealth, “Diabetes Meter at No Charge,” https://www.qualityhealth.com/registration?path=42898&ct=44546; QualityHealth, “Get Your Healthy Samples!” https://www.qualityhealth.com/registration?path=45008; QualityHealth, “FREE Diabetes Meal Planner,” https://www.qualityhealth.com/registration?path=45773&ct=47073 (all viewed 18 Oct. 2010).

[8] See also Health.com, “Health.com Media Kit: Advertiser Opportunities,” http://www.health.com/health/static/advertise-digital/online_advertisers.html; Health.com, “Sign Up Now for FREE Health.com Newsletters and Special Offers! http://www.health.com/health/service/newsletter-signup (both viewed 25 Oct. 2010).

[9] Health.com privacy policy, < http://cgi.health.com/cgi- bin/mail/dnp/privacy_centralized.cgi/health?dnp_source=E>. Last viewed December 10, 2010.

[10] Id.

[11] See for example, MedFlash < http://www.selectsafetysales.com/c-186-personal-health-record.aspx >. “MedFlash is not just your basic flash drive. It is a revolutionary personal health record (PHR) safety device that can be carried in your pocket, purse or on your keychain.” MedFlash states it is HIPAA-compliant.