Testimony: The Modern Permanent Record and Consumer Impacts from the Offline and Online Collection of Consumer Information

Background:

Written testimony of Pam Dixon about data brokers and privacy before the Subcommittee on Communications, Technology, and the Internet, and the Subcommittee on Commerce, Trade, and Consumer Protection of the House Committee on Energy and Commerce.

-

Download the testimony (PDF)

-

or Read the testimony below

—–

Testimony of Pam Dixon Executive Director, World Privacy Forum

Before the Subcommittee on Communications, Technology, and the Internet, and the Subcommittee on Commerce, Trade, and Consumer Protection of the House Committee on Energy and Commerce

The Modern Permanent Record and Consumer Impacts from the Offline and Online Collection of Consumer Information

November 19, 2009

Chairman Boucher, Chairman Rush, and Members of the Committees, thank you for the opportunity to testify today about the online and offline collection of consumer information and what that means to consumers’ everyday lives. My name is Pam Dixon, and I am the Executive Director of the World Privacy Forum. The World Privacy Forum is a 501(c)(3) non-partisan public interest research group based in California. Our funding is from foundation grants and individual donations. We focus on conducting in-depth research on emerging and contemporary privacy issues as well as on consumer education.

I have been conducting privacy-related research for more than ten years, first as a Research Fellow at the Denver University School of Law’s Privacy Foundation where I researched privacy in the workplace and employment environment, as well as technology-related privacy issues such as online privacy. While a Fellow, I wrote the first longitudinal research study benchmarking data flows in employment online and offline, and how those flows impacted consumers.

After founding the World Privacy Forum, I wrote numerous privacy studies and commented on numerous regulatory proposals impacting privacy as well as creating useful, practical education materials for consumers on a variety of privacy topics. In 2005 I discovered previously undocumented consumer harms related to identity theft in the medical sector. I coined a termed for this activity: medical identity theft. In 2006 I published a groundbreaking report introducing and documenting the topic of medical identity theft, and the report remains the definitive work in the area. I will publish a new report on this issue in January 2010, as well research and consumer education pieces about other online and offline privacy issues. [1]

Beyond my research work, I have published widely, including seven books on technology issues with Random House, Peterson’s and other large publishers, as well as more than one hundred articles in newspapers, journals, and magazines.

I am particularly interested in developments related to online and offline data flows of consumer information. Given the advances in technology that have significantly broadened and deepened the scope of consumer data collection practices, and given the new ways that these technologies and practices can shape and impact an individual’s experiences and opportunities, I believe the decisions that this Committee arrives at will be of lasting importance. Given the transition our society is undergoing from analog to digital, it is crucial to question what changes the new environment brings, what new controls it includes, and its meaning for our day-to-day lives. It is especially crucial to carefully examine and to discuss the effects these developments will have for the consumer. We must look for a fair balance between benefit, risk, and harm.

The merging of offline and online data is creating highly personalized, granular profiles of consumers that affect consumers’ opportunities in the marketplace and in their lives. Consumers are largely unaware of these profiles and their consequences, and they have insufficient legal rights to change things even if they did know.

Uncontrolled collection and accretion of information about our lives gathered from multiple sources online and offline over a course of time brings forward many complex issues, particularly those relating to privacy. I will turn to discuss these issues now.

I. The Modern Permanent Record: What Consumers Don’t Know Can in Fact Hurt Them

Consumers don’t have the ability to see or understand the information that is being collected about them, [2] and they don’t have the tools to see how that information is impacting the opportunities that are being offered – or denied – to them. This is largely due to the little-known commercial structures and methods that have evolved to collect consumer data. These activities are extremely sophisticated and complex. They often defy consumer expectations of privacy, particularly when used to compile records and facts that become a defacto “modern permanent record” that follows consumers around and influences the quality of their lives, often without their knowledge.

A. The Evolution of New Consumer Information Collection Structures and Why It Matters

In the past, detailed consumer information was largely the provenance of credit bureaus. Now the emphasis has shifted from the credit reporting system to other areas, in particular unregulated consumer reporting and data collection both online and off. These newly evolved data collection and use models merge online data collections and offline data collections to form an informational picture of the modern consumer that is profoundly detailed, comprehensive, and may be used to determine a great deal about a consumer’s experience and opportunities.

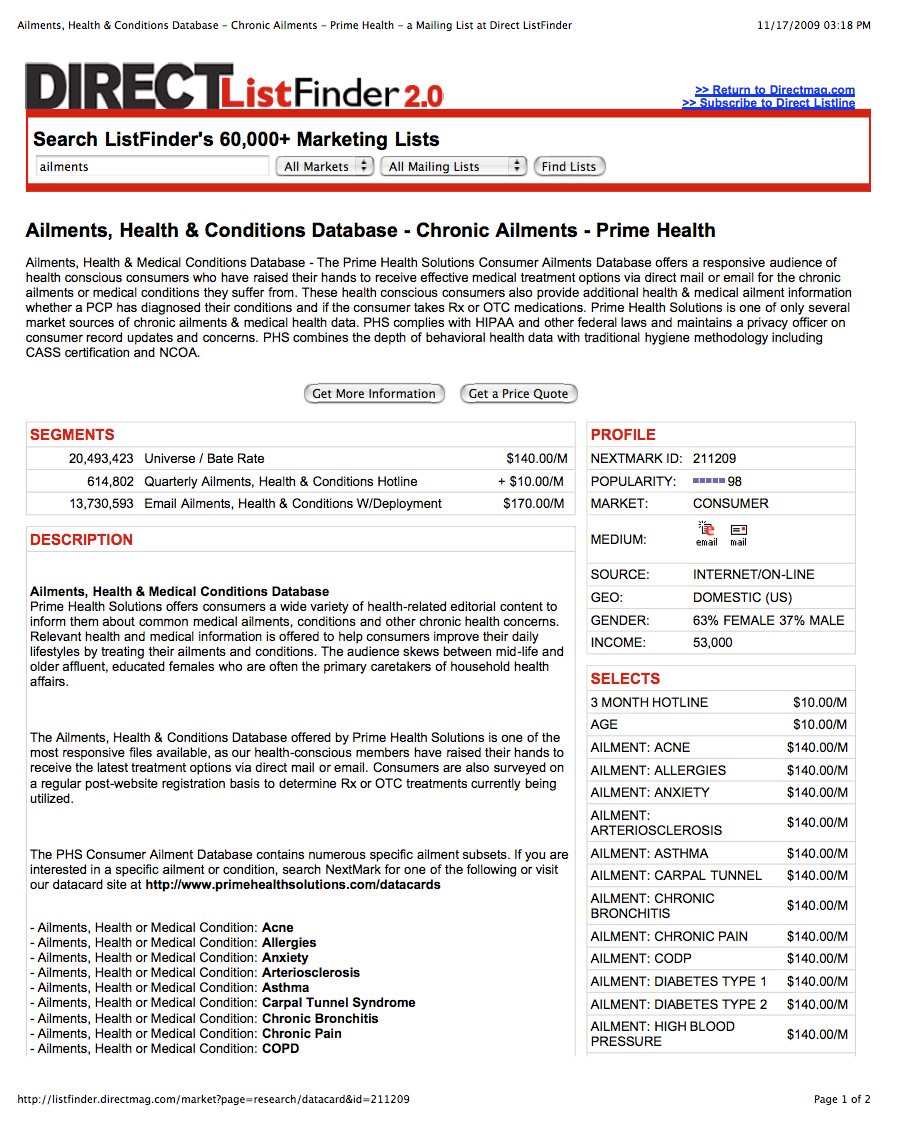

The consumer data and the merged data infrastructure may offer benefits, but the same information may also be instrumental in creating consumer harms. [3] Note a current marketing list of 20 million consumers and their medical ailments (Figure 1). These consumers landed on this Ailments, Health & Conditions list because they supposedly wanted to receive via email or direct mail “effective treatment options” for the conditions they suffer from. These are identifiable consumers who can be targeted by their asthma or their heart disease, and also by their gender, education, and other characteristics.

Figure 1

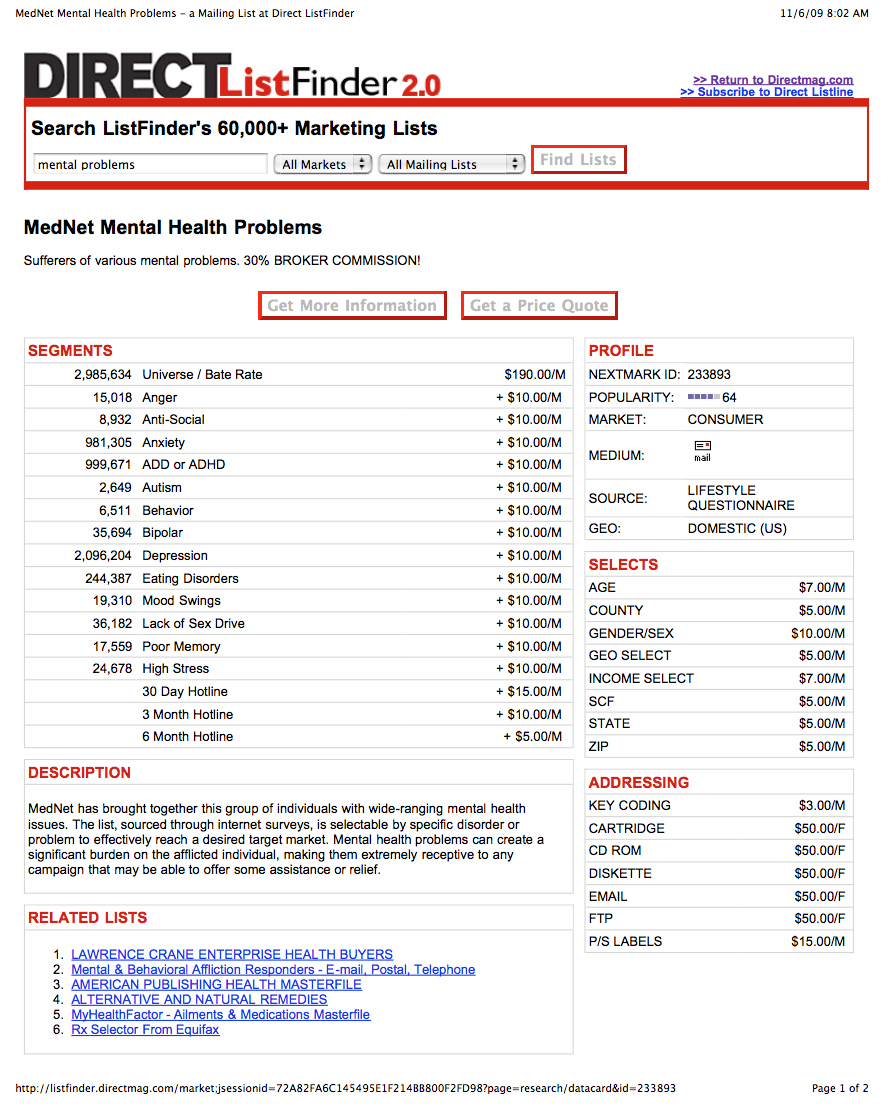

Another example of this kind of consumer data collection activity, a current marketing list of consumers who are believed to have mental illness, can be seen in Figure 2. In this list, the MedNet Mental Health Problems List, you will see that individual consumers have been

Pam Dixon testimony, p. 4

segmented or identified by age, income, gender, and more. These are not pseudonymous numbers on a computer somewhere that must be linked with other information in order to identify a consumer.

This is already identifiable consumer data that is potentially harmful to those nearly 3 million consumers listed as having anxiety, eating disorders, poor memory, autism or other conditions. This list is sourced through Internet surveys, an online modality, but the list can potentially impact consumers’ offline lives.

Figure 2

How did we arrive at a place where consumers can find themselves identified, and their information bought, sold, traded, and compiled on such lists … without their knowledge? These lists are the most visible portions of the large market that exists for consumer data, a market that is typically and intentionally obscured from our view. I would, for example, challenge any list broker or commercial data broker to allow consumers to become aware of which of these lists they are on, to what companies their names have been sold, or how many times a list has been used for marketing data to them based on the information contained in the list. I would also challenge any commercial data broker to fully reveal consumers’ complete modern permanent record for view in its totality.

The lists in Figures 1 and 2 are two small examples of a visible piece of the consumer data collection infrastructure. To understand the broader problem it is important to look at all of the consumer data collection pieces and how they fit together. To do that, I would like to walk you briefly through other pieces of this modern puzzle and how they work together to create highly individualized records of consumers.

B. Non-credit (Non FCRA) consumer databases

Non-credit, unregulated consumer reporting is a well-established business model, and has been for many years now. [4] Most consumers only find out about these databases accidentally, if at all. These are databases that contain robust and sensitive consumer information, for example, financial information or employment information. But this information is not used for purposes that fall under the Fair Credit Reporting Act, so the databases are completely unregulated. None of this is new.

What is new and has changed within the past decade is the ease of implementing this consumer data collection model. Collecting, accessing, and manipulating these types of data stores has gotten cheaper and faster. In the past, consumer information that was based on non-credit, unregulated reporting was controlled to some degree by expense of obtaining the data and the challenge of managing the databases. But now, technological advances have lowered many of the barriers.

Now there are more non-credit consumer databases in use, the databases are being used in new ways, and they are generally more accessible to more of the population. One can see this phenomenon on web sites such as Zabasearch.com. [5] There and at other similar web sites, anyone can purchase a robust file with detailed personal information about almost any individual over the Internet at minimal cost. The barriers to purchasing this information can be quite low. Often based on public record information, these files or dossiers provide basic identity, location, and history information about individuals. Again, this is not anonymous information whatsoever. It is a permanent record, with varying degrees of granularity or personalization.

These databases are one large piece of the consumer data collection picture.

C. Consumer behavior and transactional data collection, online and off

Another important piece of the consumer data collection machine is the bevy of databases containing detailed consumer behavior patterns and consumer transactions. These rich databases fill in the gaps of plain demographic information with a more three-dimensional picture of an individual. Activities that seemed so banal in the analog world – grocery shopping in a brick and mortar store, browsing books at a bookstore, looking up information about a medical condition in a paper Merck Manual and chatting about it with a close friend – these activities are now occurring increasingly digitally.

This makes it easy for these activities to be captured, stored, classified, and cataloged into behavioral profiles, which then become part and parcel of a a. If you buy a certain book and if you visit certain web sites all of the time and if you travel frequently and if you visit certain stores – all of that goes into the modern-day version of the “permanent record” school teachers used to warn students about. [6]

This highly analyzed and massaged data that has been taken from multiple sources and possibly even collected over long periods of time can be used in various ways in consumers’ lives. It is important to stress that due to the complex data merging between completely identifiable consumer information on marketing lists and previously non-identifiable information from, for example, online sources, that companies can have or find many ways of acquiring quite detailed information about people.

For example:

• An elderly veteran was bilked of his savings after he entered a sweepstakes and his name appeared on a marketing list. The list was sold by commercial data broker InfoUSA to a group of thieves, who then used the information to greatly harm him and other individuals. The story, which appeared in the New York Times, details the data trail of the veteran’s information as it was sold to criminals and then used to defraud him. [7]

“InfoUSA advertised lists of “Elderly Opportunity Seekers,” 3.3 million older people “looking for ways to make money,” and “Suffering Seniors,” 4.7 million people with cancer or Alzheimer’s disease. “Oldies but Goodies” contained 500,000 gamblers over 55 years old, for 8.5 cents apiece. One list said: “These people are gullible. They want to believe that their luck can change.”

As Mr. Guthrie sat home alone — surrounded by his Purple Heart medal, photos of eight children and mementos of a wife who was buried nine years earlier — the telephone rang day and night.”

What began as a sweepstakes response ended with a real individual on a list, which allowed him to be categorized and then sold to the highest bidder to be exploited.

- Amazon.com famously remotely deleted George Orwell’s book 1984 from its customers’ Kindle readers without users’ consent. [8] Digital tracking and use of consumers’ reading materials and records is an issue that will have to be tackled. Protecting the sanctity of book and reading material privacy is a current point of contention and discussion connected with e-books and e-readers such as Kindle, the Google Book settlement, and in other venues. [9]

- Teenaged girls who were active on Facebook were denied insurance for anorexia. When the parents sued the insurer, the insurer went to court and demanded the teens’ Facebook pages, among other things. The lawsuit was eventually settled in the plaintiffs favor. [10]

- How many Cox digital phone subscribers know that Cox is analyzing and datamining subscriber phone calls made through the Cox system and assigning a “churn” (turnover of customers) prediction to them based on the characteristics of the people or phone numbers they call? Few if any consumers expect their actual calling patterns to be analyzed in this way. [11] A datamining vendor that Cox uses, KXEN, stated in a white paper: “Cox Communications started using KXEN in September 2002 in its marketing department to analyze its customer data base. It now produces hundreds of models for marketing campaigns in 26 regional markets from a data base of 10 million customers and 800 variables. [12] Most people understand that when they sign up with a company, the company does have access to increased amount of data about them. But analyzing customer phone call patterns for further marketing purposes and behavior prediction is something I would argue that most people are not expecting.

- Consumers who walk into a store may not realize that their reactions and interactions with certain products in the store may have been recorded for marketing and profiling use. Two examples of this are gaze tracking and pathway tracking. When retail stores track consumer movements through the store, this is called pathway tracking. When digital signage displays track numbers of consumers who have passed the sign, who looked at the screen, and for how long, that is called gaze tracking. A retail expert discussed her concerns with the uses of these two shopper profiling technologies:

“During the course of 2009, we have seen more retailers utilizing shopper path tracking and gaze tracking to better understand how shoppers are responding to in-store promotions (both traditional and digitally-based). As these technology tools become more prevalent, we have seen some retailers use them responsibly and others use them to track age, race and gender with the intent to eventually serve up ‘targeted’ messages to shoppers. This raises potential privacy concern and, until we get in front of them, retailers are looking for new methods to stimulate shopper ‘opt-in’ to their targeted in-store promotions. [13] (Emphasis mine).

The industry is debating this profiling issue, with some saying that it is sufficient to notify consumers of the profiling with a sign stating that the store is using video surveillance. Others are arguing for more privacy protections. [14]

- In the realm of online consumer data collection, consumer behavior is tracked via well- established techniques such as long-term tracking cookies, Flash cookies, web browser cache cookies, web bugs or “pixel gifs” and other techniques. I discussed these techniques in a detailed analysis of the effectiveness of the Network Advertising Initiative self-regulatory program in terms of consumer protection, and incorporate that material by reference here. [15] It is tempting to place online behavioral targeting in a separate category and look at it as a separate activity. But that approach excludes the importance of the other robust data sources. A more balanced way of approaching online behavioral advertising is to understand it as one aspect of the consumer data collection picture. It is closing the circle on consumer monitoring, but it has come at the end of a long chain of other consumer data collection activities, and often operates in conjunction with those activities.

A significant segment of our modern data infrastructure began in earnest with credit reporting, which managed to overcome the costs of data collection in a pre-computerized world because of the economic incentives. The development of later styles of consumer non-credit profiling activities, with lower value, was possible only because the costs of data collection were reduced by advances in technology.

The final step, also supported by low-cost technologies, is the near-pervasive consumer data collection and monitoring that is made possible by the merging, linking and analysis of a variety of offline and online data. This will lead to a completely new kind of detailed, modern permanent record kept on individual consumers. Even the most information-conscious, privacy- sensitive consumer cannot escape being profiled.

The result of this sort of pervasive tracking and modern permanent record creation, if it is allowed to occur, will be the creation of the most detailed profiles yet on individuals, with great impact on peoples’ opportunities. Individuals who land on lists or databases with pejorative categorizations may find themselves excluded from opportunities. Those on the mental health marketing list – what opportunities have they lost? What has happened to them because of their inclusion on the list? We know what happened to at least one elderly veteran when he was included on a marketing list that identified him as an elderly opportunity seeker.

Other types of offline consumer monitoring, such as RFID, video surveillance, face recognition, cell phone tracking, and traffic monitoring are also dropping in cost. In the service of better, more efficient advertising, future consumer profiles and databases will use multiple sources of information in addition to “online” information. The additional data can include geo-location information, products that a consumer touched in a supermarket or retail store, retail items purchased in-person, and various business transactions such as activating a credit card. Commercial companies have no incentive to discard data. The costs of storage may be less than the costs of deletion.

Databases of consumer identities, demographics, transactions, and behaviors attract secondary users, and this is especially the case as the database compilers seek to find new sources of revenue. Secondary users will include government law enforcement at all levels, employers, insurance companies, schools, public health authorities, litigants, landlords, parents, stalkers, and others. The information – like credit reports – will be used to make basic decisions about the ability of individual to travel, participate in the economy, find opportunities, find places to live, purchase goods and services, and make judgments about the importance, worthiness, and interests of individuals. The information will also be used to predict consumer behavior. Under current law, this can happen without the knowledge or participation of consumers. Secondary use of unregulated, non-credit consumer information is already commonplace without any consumer awareness, with the government being perhaps a disturbingly large customer for the data.

Consumers are already being denied goods and services due to database profiles stored about them. [16] But politicians and government workers may be particularly vulnerable to the reputational aspects of increased consumer profiling. Imagine what a confirmation hearing for a Supreme Court Justice might be like in a few years, when the record of the nominee’s “lifetime Web activities” or complete Web search history or Experian Consumer Database File is demanded by the Senate. Will there be a day when a casual or accidental click may prevent anyone from fulfilling his or her personal ambitions? Will there be a day when a consumer database or combination of consumer transactional databases are used to create a compilation of facts for an opposition ad on someone running for office?

The modern permanent record will be compiled from multiple sources both online and offline, and will impact any individual who is living a modern life. It will be largely unavoidable under current law.

II. Consumer Expectations of Privacy and the Cold Reality of Data Broker Activities

Consumers go about their daily lives with certain expectations of how information about them will be collected, stored, used and disseminated. Consumers’ expectations of privacy in regards to their information and transactions are legitimate, but what consumers think is happening to their information is far removed from the reality of current business practices.

Over the years, I have watched as databases filled with consumer information gleaned from offline and online sources have been compiled, exchanged, sold, and stitched together. Marketing has changed with the times, and has become extraordinarily sophisticated. There is a good deal of focus at the Federal Trade Commission and in Congress on the use of consumer information in online behaviorally targeted advertising. There are legitimate reasons for concern in this area. However, it must be said that online behavioral advertising is just one aspect of an entire complex of consumer data collection, exchange, use, and reuse. The universe of this challenging consumer privacy issue is large indeed, and is relatively untouched by any meaningful regulation of any sort.

At the 2009 Direct Marketing Association annual meeting this October, vendors and practitioners discussed the latest advances in real-time consumer tracking, micro-targeting to the individual, and data appending, with plentiful examples. Of note was the persistent emphasis of merging online and offline information sources. [17] Also of note was a strong emphasis on predicting consumer behavior based on past behavior, or even on known relationships with other businesses or other consumers. The discussions at this event generally typify the industry trends.

In the past, marketers focused on acquiring certain discrete pieces of information about the customer. For example, acquiring the age, gender, ethnicity, etc. of a customer was a prime goal. But now, as discussed earlier, demographic information is just the beginning. Transactional information tied to individual consumers, sliced and diced into scores and predictions, that is the newer model. I would like to discuss some of these new approaches in more detail.

A marketing list called Consumer TransactionBase had this to say about why a list of 77 million- plus consumers was so valuable:

Transactional data can be leveraged by direct marketers to gain powerful insight into a household’s needs and wants. Through the examination of past spending patterns, marketers are able to analyze and predict future purchasing behaviors.

Consumer TransactionBase compiles SKU-level transactional data from a variety of online and offline retailers to offer a complete view of economically active purchasing households. Additional uses for this detailed data set include modeling and analytics as well as data enhancement.

Major applications include:

Book and Magazine Subscriptions

Club Memberships

Donation Requests

Financial Products and Services

Lifestyle and Interest-Specific Offers

Personal Services

Store Announcements Travel Offers

The Consumer TransactionBase file is updated quarterly. Compilation comes from a leading nationwide cooperative database of consumer purchasing activity. Company and industry usage restrictions may apply. [18] (Emphasis ours)

What does all of this mean to consumers? If consumers simply go about their daily lives, are cautious with their information, careful with who sees their Social Security Number, shred their bills and pre-approved credit card offers, use safe computing practices, and so forth, they will still have detailed information about their private and in some cases professional lives collected, bundled, bought, trade, sold, compiled, layered, appended, and in general, used in various ways to target or to deny goods, services, and opportunities.

Right now, consumers do not generally know what is happening to them, and if they did, they do not have sufficient rights to manage the information marketplace they find themselves in. Regardless of how cautious and informationally careful a consumer is, he does not have the ability to live a modern life and avoid being systemically profiled. Consumer profiling is currently unavoidable by the majority of consumers. I believe this truly defies consumer expectations of privacy.

The sheer volume of profiling data already being exchanged about consumers can be seen in the Experian Consumer Database. This database contains approximately 215 million consumers in 110 million living units nationwide.

The data card (or sales card) for the list states:

Target people by exact age, gender, estimated income, marital status, dwelling type, families with children, telephone numbers and a variety of other selections. The vast quantity of names on this database and its varied selection capabilities make this one of the largest and most flexible lists on the market today.

The data card additionally states in regards to predictive targeting:

Experian’s Quick PredictSM modeling process is designed for marketers with small to medium-size customer databases that are looking for a cost-effective modeling solution. Quick Predict gives you fast results for acquisition, retention and cross-sell campaigns and to enhance your market research efforts. of current customers. We run acquisition models against Experian’s extensive consumer data resources, providing you with a steady stream of potential new customers.

Quick Predict segmentation uses either customer surveys, market research or observed behaviors of your existing customers to create specific propensities (or scores) based on your own objectives. The Quick Predict process matches your file to the INSOURCE[SM] Database to determine households that behave like your target customers. [19]

This is not the staid marketing list in use in years past – this is a list that is flexible, is used to create scores that predict consumer behavior, and is used to characterize consumers and put them in boxes of how they are predicted to behave. Opportunities and services are then offered to the consumers to match their modern permanent record. At what point does the contents of a modern permanent record accumulated through web links clicked, Facebook surveys, Twitter streams, sweepstakes, loyalty card programs, and the like become a person’s destiny?

To take a different concrete example of a data collection that most everyone can identify with, customers at retail stores who are asked for their zip code do not understand that the zip code they are offering leads to a universe of additional new information about them. This practice of “data appending” in the retail environment is a significant point of data collection. While the zip code may be acquired at the retail cash register, that zip code can be and in some cases is merged with substantial amounts of other information, including information from other databases, which may include offline and online information. A recent court case has exposed the facts about how the inner workings of this occurs. [20]

This sort of data activity – prediction, analysis, data appending — is often trivialized by those using the data. One frequently encountered argument is that this data activity is fine, because consumers want better ads, products, and services. But there is no good empirical proof that consumers want an entire modern permanent record created in order to get a better ad. Beyond that, it is crucial to understand that this profiling is not just being used to offer services and goods; it is also used to deny consumers opportunities, products and services. This is especially problematic when predictive analysis based on transactional data is used to categorize consumers in a negative way.

Note for example, the database of consumers who have disputed charges on their bills; certain of these customers are put into a database that is marketed as “Badcustomer.” This is modern permanent recordkeeping at its worst. The badcustomer.com web site states: “Are your purchasing transactions being denied? Find out if you’ve been blacklisted before it’s too late.” [21] Consider the consequences of this database for identity theft victims — these are individuals who have to dispute charges. Are they in this database? What services, goods, and opportunities will victims of identity theft be denied because they are in this database? How many lists like this exist that consumers don’t know anything about?

I also note that to get off the Badcustomer list, consumers must supply detailed information online. How are consumers supposed to learn about databases like this? How is Badcustomers.com using the consumers’ information after receiving it? Is this company doing more than just taking people off of the bad customer list?

I suggest that consumer data collection is out of control, with no balancing consumer rights or requirements for transparency to counterweight the collection and usage activity. As I will discuss in this testimony, I believe the institution of a rights-based approach that combines Fair Credit Reporting Act-like rights with additional Fair Information Practices rights will address this lack of balance.

Most consumers would be appalled to discover the ways their modern permanent record contains categories that describe them and circumscribe and determine their opportunities. For example, on a recent search I found 18,684 marketing lists containing the keyword “bad credit.” I found 414 marketing lists containing the keyword “impulse.” I found 1,282 marketing lists containing the key word “mental problems.”

As seen earlier, these marketing lists contain names of millions upon millions of consumers, along with typically their name, age, gender, income, state, and a great deal of other detailed demographic information. Some lists also contain transactional information and merged information. These lists exist outside of most regulatory structures. Many consumers often have a vague idea that HIPAA will protect their health information no matter where that information exists. These consumers would be horrified to learn that it is not unusual whatsoever to find highly sensitive health information offered up for sale in these lists.

I have already shown you the MedNet Mental Health Problems list. Many of the consumers named on this list are not likely to know they are on the list. I also think that many of the consumers named on this list would welcome the option to delete their names and identifying information from this list, which is marketed with this pitch:

In this list, the data card (a form of “sales pitch” for the list) states:

“Mental health problems can create a significant burden on the afflicted individual, making them extremely receptive to any campaign that may be able to offer some assistance or relief.” [22]

Returning to the issue of targeted marketing and how consumers purportedly like it, it is unlikely that the caretaker of an autistic adult would be happy to know that she is being targeted because she will be “extremely receptive” to certain types of campaigns.

I also think that some of the 6 million people on the Credit Card Declines marketing list would like to know they are on a list of people who have been declined for major bank cards, and would like the opportunity to delete their age, the age of their children, the gender of their child, dwelling type, ethnicity, and other information from the list and databases associated with it. [23] How does being on this list impact their modern permanent record?

There is an industry argument that consumers land on these lists and in these databases because they have given up their information freely. This may have been true at one time, but it no longer holds universally true. Consumers can get on these lists from freely giving up their information. But they can also get on these lists just from making a wrong stray click on a web site, opening a phishing email by mistake, or even by just conducting their lives. Even the most informationally careful consumer can land on these lists. This completely defies consumers’ expectations of privacy and of fair play.

One example of this is the Passport to Credit – Newly Activated Credit Cards list. This list of 18 million consumers is sourced from a credit card transaction processor.

This dynamic database is sourced from a credit card transaction processor, not from the source who issues the cards. You can select change of address, number of transactions, number of credit cards, type of credit card and more! [24]

To stay off of this list, a consumer would have to not activate their credit card. How is that a reasonable choice?

Some lists and databases are an assault on the dignity of the people named in the list. One list, Fat Burner II, targets obese and morbidly obese consumers. The data card states: “These weight watching consumers will try anything in hopes of being healthy.” [25] Another list, Free to Me – Impulse Buyers, is targeted to people who made recent online purchases because they received something free with their purchase. The data card states: “Free To Me – Impulse Buyers are very quick to respond to offers that come in the form of contests, sweepstakes, or other free products and services.” [26]

Loyalty cards, warrantee cards, sweepstakes, and many more items in this realm create a raft of information that flows into the modern permanent record. [27] Online information also flows into the modern permanent record. [28] As modern permanent records become an important influence on consumers’ opportunities, much like the credit score did, consumers will need new rights to manage the situation they find themselves in.

III. The FCRA Model and Offline/Online Privacy

Perhaps the most successful — but not perfect — privacy law of longstanding is the Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA). Congress passed the FCRA after years of persistence by a Senator who understood (1) the essential importance of credit reports in the lives of consumers and in the operation of the economy, and (2) the lack of any rights or due process for consumers in the credit reporting system.

The activities regulated under the FCRA are absent from my discussion of consumer harms, because the regulations have been largely effective. Commercial data brokers do not want to fall under the FCRA compliance regime, and many avoid FCRA activities as a result. They avoid knowing how their information is used in the real world.

What is needed is a fresh look at the ideas contained in the FCRA and how its principles could be used to create variegated rules for the modern online/offline information environment. When information – whether demographic, online, behavioral, pictorial, or etc. might affect a consumer’s rights, benefits, privileges, or opportunities in government, commercial space, or on the Internet, there should be some rules of the road that prevent consumer harms and give consumers rights. Modern permanent records should be subject to rules.

Some ideas:

- Some harmful collection and data storage activities should be banned altogether. For example, forms of redlining that would be impermissible in the analog world should also be impermissible in the digital world.

- Other consumer data compilation and use activities should have disposal requirements, much stricter than the seven years allowed under the FCRA.

- The compilation of some categories of sensitive information should be allowed only with the affirmative, time-limited consent of the data subject. Examples include medical and financial information, for example.

- Individuals should have the right to stop harmful dossier activity and to force the permanent and immediate expungement of all data that is factually incorrect, data that arrives at an incorrect conclusion about them, or data that influences decisions about a consumer in a negative way.

- Modern permanent records associated with an individual should be banned for anyone under the age of 16, and all pre-existing dossiers on individuals should be expunged when they reach the age of majority.

- Consumers should have a right to see and change their modern permanent records at no cost

The legislation needed to implement these ideas will be quite complex, will require long-term discussions from all stakeholders. None of this will be easy. However, what is most important is that we recognize the stakes in the current limited public debate about online behavioral ad targeting. Discussions that focus solely on consumer opt in and opt out in the online environment miss the point of the modern information environment: a consumer could opt out of everything online, but that would not have a substantive impact, because the digitization of our lives is profoundly more complete than that already. And the uses of that information are already in place, and will only increase in scope.

The issue that a democratic society must debate is whether the prize here – completely unregulated use of consumer data for slightly more efficient advertising or marketing – is worth the full cost and the consequences. Mild-mannered limitations on behavioral targeting that some are considering at present will not be enough to head off the deeper problems that loom. Consumers need substantive control over their data. Consumers need to know about their own modern permanent records and to be able to mitigate its impacts on their lives. We need to look further down the road and build appropriate protections.

The stakes here are far greater than Internet advertising or the current model for Internet services. We need to remember what was happening with credit reports before the FCRA. In a similar manner, online and other forms of digital tracking will record the tiniest details, and these details will be used to control, shape, and affect consumer activities in subtle and not-so-subtle ways. This is what happened with credit reports, which have found other uses in spite of regulation. [29]

The importance of non-credit related consumer profiles in our lives will exceed the importance of credit reports if the non-credit profiles remain completely unrestricted. We need to develop regulatory protections that will place limits on these activities before these practices become cheaper and even more entrenched in business practices.

IV. Privacy Standards

We have a good set of information privacy standards that were created originally in the United States, that have been blessed in U.S. and foreign legislation, and that are perfectly adaptable for present purposes. Those standards are Fair Information Practices (FIPs). For a short history of FIPs, see Robert Gellman, Fair Information Practices: A Basic History. [30]

The version of FIPs from the Organisation for Economic Cooperative and Development represents the gold standard of information privacy principles. [31] The eight principles set out by the OECD are:

Collection Limitation Principle

There should be limits to the collection of personal data and any such data should be obtained by lawful and fair means and, where appropriate, with the knowledge or consent of the data subject.

Data Quality Principle

Personal data should be relevant to the purposes for which they are to be used and, to the extent necessary for those purposes, should be accurate, complete, and kept up-to-date.

Purpose Specification Principle

The purposes for which personal data are collected should be specified not later than at the time of data collection and the subsequent use limited to the fulfillment of those purposes or such others as are not incompatible with those purposes and as are specified on each occasion of change of purpose.

Use Limitation Principle

Personal data should not be disclosed, made available or otherwise used for purposes other than those specified in accordance with [the Purpose Specification Principle] except: a) with the consent of the data subject; or b) by the authority of law.

Security Safeguards Principle

Personal data should be protected by reasonable security safeguards against such risks as loss or unauthorized access, destruction, use, modification or disclosure of data.

Openness Principle

There should be a general policy of openness about developments, practices and policies with respect to personal data. Means should be readily available of establishing the existence and nature of personal data, and the main purposes of their use, as well as the identity and usual residence of the data controller.

Individual Participation Principle

An individual should have the right: a) to obtain from a data controller, or otherwise, confirmation of whether or not the data controller has data relating to him; b) to have communicated to him, data relating to him within a reasonable time; at a charge, if any, that is not excessive; in a reasonable manner; and in a form that is readily intelligible to him; c) to be given reasons if a request made under subparagraphs (a) and (b) is denied, and to be able to challenge such denial; and d) to challenge data relating to him and, if the challenge is successful to have the data erased, rectified, completed or amended.

Accountability Principle

A data controller should be accountable for complying with measures, which give effect to the principles stated above.

In 2000, the Federal Trade Commission issued its own incomplete version of FIPs. [32] That statement of FIPs appears to have been abandoned, and it should not be revived. We see no reason to deviate from the FIPs principles in general use around the world.

To be sure, the OECD version of FIPs principles may not be perfect. There may be a need to consider, for example, whether there should be a principle addressing anonymity or pseudonymity. Nevertheless, the principles as they exist today are broad enough and general enough for the purpose.

V. Conclusion

In this testimony, I have discussed the modern permanent record, business practices in the online and offline world, and how online and offline data is being merged and linked. I have given concrete examples of current practices already in place. Why does any of this matter? The online and offline data collection of consumer data matters because it impacts all of our lives profoundly whether we know it or not.

Yes, there are benefits. But there are harms. But the most important idea I would like to convey to you is that information collection and use today is already robust enough and rich enough to influence what a person’s world looks like to them. Two people going to one web site or one retail store could already be offered entirely different opportunities, services, or benefits based on their modern permanent record comprised of the previous demographic, behavioral, transactional, and associational information accrued about them. These same two people can also be subject to a denial of opportunities, services or benefits based on analysis of the same information.

It is still possible to avoid an environment where our demographic characteristics analyzed in combination with our online and offline activities (links clicked, people emailed, friends or businesses associated with) will be judged by a merchant, credit grantor, employer, insurance company, landlord, etc. to make a decision or a prediction about us. Do we want to live in a world where every small choice we make — from who to call, what store to window shop, what street to drive down, who to friend, what to order for lunch — will be weighed and assessed and possibly used in our lives? Do we want to arrive at a point where people hesitate to buy things, go places, or even use the Internet lest it all be recorded in their modern permanent record maintained by some unknown company and over which they have no rights?

Thank you for your attention to these matters. I welcome your questions, and will be happy to provide further research or input.

______________________________________

Endnotes:

[1] Much of my privacy-related research work and writings are available at the World Privacy Forum web site, <https://www.worldprivacyforum.org>.

[2] See, for example, a new Carnegie-Mellon study on one aspect of consumer data collection, behaviorally targeted online ads. This study found that “many participants have a poor understanding of how Internet advertising works, do not understand the use of first-party cookies, let alone third-party cookies, did not realize that behavioral advertising already takes place, believe that their actions online are completely anonymous unless they are logged into a website, and believe that there are legal protections that prohibit companies from sharing information they collect online.” Aleecia M. McDonald and Lorrie Faith Cranor, Carneigie Mellon University, An Empirical Study of How People Perceive Online Behavioral Advertising, Nov. 10, 2009.

[3] See for example Karen Blumenthal, How Banks, Marketers Aid Scams, Wall Street Journal, July 1, 2009, available at <http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052970204556804574260062522686326.html>.

[4] Non-FCRA consumer databases may contain nearly identical information as a database that would be regulated under the FCRA, however, they are not used for FCRA purposes, therefore do not fall under the statute. These databases take on a wide variety of characteristics, ranging from anti-fraud to marketing to identity verification. Some examples include: Fair Isaacs FICO Falcon Fraud Manager < http://www.fico.com/en/Products/DMApps/Pages/FICO-Falcon-Fraud-Manager.aspx> This database analyzes detailed financial information of more than 1.8 billion accounts for fraudulent activity. Other kinds of non-credit databases contain large amounts of detailed information about consumers. See Acxiom’s Consumer Insight Products databases, <http://www.acxiom.com/products_and_services/Consumer%20Insight%20Products/Pages/Consumer%20Insight% 20Products.aspx> which offers “Deep consumer insights — in the form of Acxiom’s data enhancements, lists, demographics, segmentation and buying behavior…”. The Work Number, < http://www.theworknumber.com/> is a consumer database designed to verify income and employment, among other things.

[5] <www.zabasearch.com>.

[6] Daniel Solove’s book, The Digital Person, offers an important and extended discussion of how people now leave “digital breadcrumbs” as they live normal contemporary lives. The book offers an excellent legal analysis of the implications of what this means now and in the future. Solove, Daniel J. The Digital Person: Technology and Privacy in the Information Age. NYU Press, 2004.

[7] Charles Duhigg, Bilking the Elderly with a Corporate Assist, New York Times, May 20, 2007. <http://www.nytimes.com/2007/05/20/business/20tele.html?_r=1>.

[8] Brad Stone, Amazon erases Orwell books from Kindle devices, New York Times, July 17, 2009. <http://www.nytimes.com/2009/07/18/technology/companies/18amazon.html?_r=1>.

[9] See for example EPIC, Google Books Settlement and Privacy. <http://epic.org/privacy/googlebooks/default.html>,

[10] Mark Stein, Facebook page or Exhibit A in Court? Portfolio.com, Feb. 5, 2008. <http://www.portfolio.com/views/blogs/daily-brief/2008/02/05/facebook-page-or-exhibit-a-in-court/>. See also Mary Pat Gallagher, MySpace, Facebook Pages Called Key to Dispute Over Insurance Coverage for Eating Disorders, New Jersey Law Journal <http://www.insuranceheadlines.com/pdf/4479.html>.

[11] Direct Marketing Association 09 Conference and Exhibition Presentation, Automated Predictive Modeling: Cox Communications Shows It’s Possible, October 20, 2009, San Diego, California. Presentation abstract: “Can you imagine being able to refresh, validate and deploy your cross-sell and retention models every month? For 20 separate regions of the country, and 19 different products? Cox Communications will explain how they do this with KXEN. Now they can focus on the business, not the models.” < http://mydma09.bdmetrics.com/SOW- 2820200/Automated-Predictive-Modeling-Cox-Communications-Shows-It-s-Possible/Overview.aspx>. See also DMA 2009 Program, <http://www.dma09.org/>.

[12] KXEN, Making More Decisions Intentionally and Competing on Analytics in the Real World, KXEN White Paper < www.wgsystems.com.br/kxen/pdf/KXEN_extreme_data_mining.pdf> last accessed Nov. 17, 2009. KXEN is a data mining automation company.

[13] Laura Davis-Taylor, 2-D Barcodes present path to get shoppers to “opt-in” to in-store, Retail Touch Points, August 6, 2009. < http://www.retailtouchpoints.com/in-store-insights/295-retail-technology-trends-2-d-barcodes- for-shopper-opt-in-.html>.

[14] Laura Davis-Taylor, The in-store shopper profiling debate, May 20, 2008, POPAI Digital Signage Blog. < http://www.popaidigitalblog.com/blog/articles/The_in_store_shopper_profiling_debate-439.html>.

[15] Dixon, Pam. World Privacy Forum, The Network Advertising Initiative: Failing at Consumer Protection and at Self-Regulation, Nov. 2, 2007. < https://www.worldprivacyforum.org/pdf/WPF_NAI_report_Nov2_2007fs.pdf>.

[16] See <http://www.badcustomer.com>.

[17] See for example the online optimization track <http://www.dma09.org/attendees/conference/Online.php?PHPSESSID=a3a74c1e2658569a8b6ea3333679edd3> and trigger marketing <http://www.dma09.org/attendees/conference/Trigger.php?PHPSESSID=a3a74c1e2658569a8b6ea3333679edd3> in the program.

[18] Consumer TransactionBase, <http://listfinder.directmag.com/market;jsessionid=D111DD2A12B5CAE409CBCBE160539072?page=research/dat acard&id=267942> last accessed November 6, 2009.

[19] Experian Consumer Database, Nextmark ID 84312, Last accessed Nov. 6, 2009. <http://listfinder.directmag.com/market;jsessionid=749F1DAB78232862B6E4A48F4C9A7120?page=research/data card&id=84312>.

[20] See Pineda v. Williams-Sonoma Stores, Inc., Cal. Ct. App., 4th Dist., No. D054355, certified for publication 10/23/09.

[21] <https://www.badcustomer.com/blacklist.htm>. Last accessed November 6, 2009.

[22] MedNet Mental Health Problems, Nextmark ID 233893. <http://listfinder.directmag.com/market?page=research/datacard&id=233893>.

[23] Credit Card Declines, Nextmark ID 138236, last accessed November 6, 2009.

[24] Passport to Credit – Newly Activated Credit Cards, Nextmark ID 257747, last accessed Nov. 6, 2009.

[25] Fat Burner II, Nextmark ID 206453, last accessed November 6, 2009.

[26] Free To Me – Impulse Buyers, Nextmark ID 271702, last accessed November 6, 2009.

[27] See Givens, Beth, Privacy Rights Clearinghouse, The Information Marketplace: Merging and Exchanging Consumer Data , April 30, 2001 for further discussion of these issues. < http://www.privacyrights.org/ar/ftc- info_mktpl.htm>.

[28] See for example Rapleaf <http://www.rapleaf.com>. Rapleaf is promising to use consumer data gleaned from Twitter and other social networks to predict credit risk. This activity is broadly termed “Social Media Monitoring” or SMM. See Conley, Lucas, How Rapleaf is Data Mining Your Friend Lists to Predict Your Credit Risk, FastCompany, Nov. 16, 2009. < http://www.fastcompany.com/blog/lucas-conley/advertising-branding-and- marketing/company-we-keep>.

[29] For example, the credit scoring phenomenon. See Hendricks, Evan. Credit Scores and Credit Reports, How the System Really Works, What you Can Do, 3rd edition. Atlas Books.

[30] Robert Gellman, Fair Information Practices: A Basic History <http://bobgellman.com/rg-docs/rg- FIPshistory.pdf>.

[31] < http://www.oecd.org/document/18/0,2340,en_2649_34255_1815186_1_1_1_1,00.html>. There are equivalent statements from the Council of Europe and from the Canadian Standards Association, but the differences are minor. The Privacy Office at the Department of Homeland Security in 2008 issued its own Fair Information Practice Principles that that match closely the OECD version. Privacy Policy Guidance Memorandum (2008) (Memorandum Number 2008-1), <http://www.dhs.gov/xlibrary/assets/privacy/privacy_policyguide_2008-01.pdf>. The DHS issuance is noteworthy since it implements the first statutory reference to fair information practices in U.S. law.

[32] Federal Trade Commission, Privacy Online: Fair Information Practices in the Electronic Marketplace, (May 2000), http://www.ftc.gov/reports/privacy2000/privacy2000.pdf.