Congressional Testimony: What Information Do Data Brokers Have on Consumers?

This testimony was given to the Senate Commerce Committee on December 18, 2013 at a hearing dedicated to shedding light on data broker industry practices and how that affects consumers. The full testimony contains numerous examples of data broker activities, consumer scoring, and discusses the solutions that are needed, including a requirement for data broker opt out.

Author: Pam Dixon

-

Read Full Testimony (PDF, 40 pages)

-

See the live CSPAN video of the testimony before the Committee — Pam Dixon, Executive Director (Video: Vimeo or You Tube)

———–

Written testimony is also available below:

Testimony of Pam Dixon

Executive Director, World Privacy Forum

Before the Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation

What Information Do Data Brokers Have on Consumers, and How Do They Use It?

December 18, 2013

Chairman Rockefeller and Members of the Committee, thank you for the opportunity to testify today about data brokers, an industry that is often hidden from public view, and the impact of data brokers on consumers’ lives. My name is Pam Dixon, and I am the founder and Executive Director of the World Privacy Forum. [1] The World Privacy Forum is a 501(c)(3) non-partisan public interest research group based in California. We focus on conducting in-depth research on emerging and contemporary privacy issues as well as on consumer education.

I have been conducting privacy-related research since 1998, first as a Research Fellow at the Denver University School of Law’s Privacy Foundation where I researched privacy in the workplace and employment environment, as well as technology-related privacy issues such as online privacy. While a Fellow, I wrote the first longitudinal research study benchmarking data flows in employment online and offline, and how those flows impacted consumers.

After founding the World Privacy Forum, I wrote numerous privacy studies and commented on numerous regulatory proposals impacting privacy as well as creating useful, practical education materials for consumers on a variety of privacy topics. A few months ago, we published a report on data brokers and the Federal government, Data Brokers and the Government, which examined current law and practices in regards to the eligibility use of data brokers in particular. I have published many additional studies. Previously, in 2005 I discovered previously undocumented consumer harms related to identity theft in the medical sector. I coined a termed for this activity: medical identity theft. In 2006 I published a groundbreaking report introducing and documenting the topic of medical identity theft, and the report remains the definitive work in the area. [1] In 2010 I also published the first report on digital and retail privacy, The One Way Mirror Society: Privacy Implications of Digital Signage Networks. I have also written several well-known reports on self-regulation, and in 2012-2013, was a lead drafter in the NTIA MultiStakeholder Process for Mobile App Short Form Notices.

Beyond my research work, I have published widely, including a reference book on privacy, Online Privacy, and seven books on technology issues with Random House, Peterson’s and other large publishers, as well as more than one hundred articles in newspapers, journals, and magazines.

I appreciate the dedication and work of Senator Rockefeller in bringing much-needed attention to the issue of data brokers, which prior to his attention, was languishing on legislative backburners.

Introduction & Summary

What do a retired librarian in Wisconsin in the early stages of Alzheimer’s, a police officer, and a mother in Texas have in common? The answer is that all were victims of consumer data brokers. Data brokers collect, compile, buy and sell personally identifiable information about who we are, what we do, and much of our “digital exhaust.”

We are their business models. The police officer was “uncovered” by a data broker who revealed his family information online, jeopardizing his safety. The mother was a victim of domestic violence who was deeply concerned about people finder web sites that published and sold her home address online. The librarian lost her life savings and retirement because a data broker put her on an eager elderly buyer and frequent donor list. She was deluged with predatory offers.

These people — and 320 million others in the United States — are not able to escape from the activities of data brokers. Our research shows that only a small percentage of known consumer data brokers offer a voluntary opt out. These opt outs can be incomplete, extremely difficult, and must typically be done one-by-one, site-by-site. Often, third parties are not allowed to opt individual consumers out of data brokers.

This state of affairs exists because no legal framework requires data broker to offer opt out or suppression of consumer data. Few people know that data brokers exist, and beyond that, few know what they do. There are about 4000 data brokers. Despite the large and growing size of the industry, until this Committee started its work, this entire industry largely escaped public scrutiny.

Privacy laws apply to credit bureaus and health care providers, but data broker activity generally falls outside these laws. Even a knowledgeable consumer lacks the tools to exercise any control over his or her data held by a data broker. It doesn’t matter that the data is about the consumer. The data broker has all the rights, and the consumer has none.

Consumers have no effective rights because there is no legal framework that requires data brokers to offer consumers an opt out or any other rights. Privacy laws apply to credit bureaus and health care providers, but data broker activity generally falls outside these laws. Even a knowledgeable consumer lacks the tools to exercise any control over his or her data held by a data broker. It doesn’t matter that the data is about the consumer. The data broker has all the rights, and the consumer has none.

In my testimony, I will discuss consumer data brokers, businesses that traffic in consumer data. The data broker industry is complex, and I can only focus on a few aspects of it.

There are consumer list brokers that sell lists of individually identifiable consumers grouped by characteristics. To our knowledge, it is not practically possible for an individual to find out if he or she is on these lists. If a consumer learns that he or she is on a list, there is usually no way to get off the list. Some exceptions exist, but the rule is that the lists are circulated far from consumers’ eyes.

Lists reveal information that would surprise most people. Data brokers sell lists of people suffering from mental health diseases, cancer, HIV/AIDS, and hundreds of other illnesses. Data brokers sell lists of people who live in or near trailer parks so that these undesirable consumers can be targeted for suppression. Data brokers sell lists of people who are late on payments, often to those who make predatory offers to those in financial trouble. Data brokers sell lists of people who are impulse buyers or “eager senior buyers.” All in all, there are millions of lists.

In addition to list brokers, there are people finder services that sell consumer demographic information online. The hundreds of “people finder” web sites online are also part of the data broker industry. Statistically, few of these sites give individuals a meaningful opportunity to have their information removed from their databases. A handful do offer a partial or complete opt out or suppression, but to exercise the opt out, consumers have to first find the site, then go through what can be an incredibly frustrating series of hoops. Scanning drivers’ licenses, sending the opt-out through postal mail, and sometimes paying as much as $1,000.00 to opt out. A consumer who successfully negotiates an opt-out at one data broker faces the challenge of doing the same thing at dozens or hundreds of other data brokers. There is always the risk that a name removed today will be added back tomorrow.

I will also discuss consumer scores, a growing area of data broker activity. Consumer scores are not well-known yet, but their influence on consumers is profound. One important example is the modeled consumer credit score. The modeled consumer credit score consists entirely of non-credit elements. Why? Because this allows the consumer data broker industry to avoid giving consumers the rights that the Fair Credit Reporting Act provides.

I will offer some solutions focused on addressing the problems identified in my testimony. The solutions I propose are practical and possible. The solutions are designed to bring fairness and rights to consumers. The data broker industry has not shown restraint. Nothing is out of bounds. No list is too obnoxious to sell. Data brokers sell lists that allow for the use of racial, ethnic and other factors that would be illegal or unacceptable in other circumstances. These lists and scores are used everyday to make decisions about how consumers can participate in the economic marketplace. Their information determines who gets in and who gets shut out. All of this must change. I urge you to take action.

The Structure of the Data Broker Industry and Why it Matters

The data broker industry is complex, layered and multi-faceted, and it is evolving rapidly. The industry cannot readily be described as just consumer information being sold on flat lists. There is much, much more than that.

A way to start approaching an understanding is to look at some key aspects of the industry.

Size: The data broker industry, by its own estimation, numbers in the neighborhood of 3,500 to 4,000 companies. Most data brokers engage in multiple activities and have a range of core expertise.

Scope: Data brokers range in scope from multi-national corporations with revenues in the billions to small sole proprietors operating locally. Some data brokers operate offshore.

Shape of the long tail: This industry has a relatively small number of very large name brand companies, and many more small to mid-size companies. The tail of this industry is very long, and the end of the tail works its way down from large companies to small affiliates selling data online.

Activities: These include list brokering, data analytics, predictive analytics and modeling, scoring, CRM, online, offline, APIs, cross channel, mailing preparation, campaigns, and database cleansing.

Data flows: Some data brokers host their own data and are significant purchasers of original data. Acxiom is an example of this kind of company. Some primarily analyze data and come up with scoring and Return on Investments proofs. Datalogix is an example of this kind of company. Some sell or resell consumer information online. Intelius is an example of this kind of company. There are many other models in addition. Some data moves from online to offline and back; some through social media and back. The point is that the business models and data flows are complex, use many sources, and differ between types of data brokers.

Affiliate Storms: One common model results in the flow of information from the largest name-brand companies to the smaller companies, who then turn around and resell the data to a third tier of “affiliates” who then market the information themselves, or to another downstream affiliate. The term I use for this is “affiliate storm.” A consumer at the end of all of the data reselling has difficulty finding the original compiler and seller of the data.

Regulation: The 2013 GAO report on data resellers outlined the lack of regulatory oversight regarding data brokers. [2] There are additional concerns that some existing regulations are being circumvented in some cases.

My comments today address the consumer-focused aspects of data brokers. Some activities of data brokers do not affect consumers in a negative or unfair way. Some list cleansing or compliance activities to bring the data broker in line with the Do Not Call list are unobjectionable. My testimony is about the other consequences of the data broker business today.

Sources for Data Broker Data

The sources for data broker data have become more complex as the industry has grown, and as the information systems have become more digitized. Consumers sometimes have a choice about whether they give data; other times, they do not. Even if a consumer paid mainly cash and lived very quietly, using shredders for their mail and records and keeping their SSN to themselves, the likelihood that the consumer could totally avoid landing on a data broker list is quite small. Most people in the US are in many data bases and on many lists.

Some of the most common sources of consumer data include: (marketing, not credit data)

• Retailers and merchants via Cooperative Databases and Transactional data sales & customer lists

• Financial sector non-credit information (PayDay loan, etc.)

• MultiChannel direct response

• Survey data, especially online

• Catalog/phone order/Online order

• Warranty card registrations

• Internet sweepstakes

• Kiosks

• Social media interactions (dependent on data broker interactions/agreements)

• Loyalty card data (retailers)

• Public record information

• Web site interactions, including specialty or knowledge-based web sites

• Lifestyle information: Fitness, health, wellness centers, etc.

• Non-profit organizations’ member or donor lists

• Subscriptions (online or offline content)

Following are some source examples from data broker cards, these examples are not surprising or out of the ordinary.

On a Baby Boomers data card, Adrea Rubin gave this source data:

Source: Multichannel Direct Response, Survey Data, and Public Record Information [3]

On a data card for a Transaction Database, the company listed the source as:

Source: 79% catalog/phone order/Online, 21 % retail. [4]

On a data card describing extreme mail order buyers, the source for gender, age, income, number of purchases, and number of credit cards was cited as

Source: Multi-source, consolidated from a variety of sources, overlaid with co- op/transactional data[1]

A data card listing seniors listed the source as warrantee cards. Source: Warrantee card registrations [5]

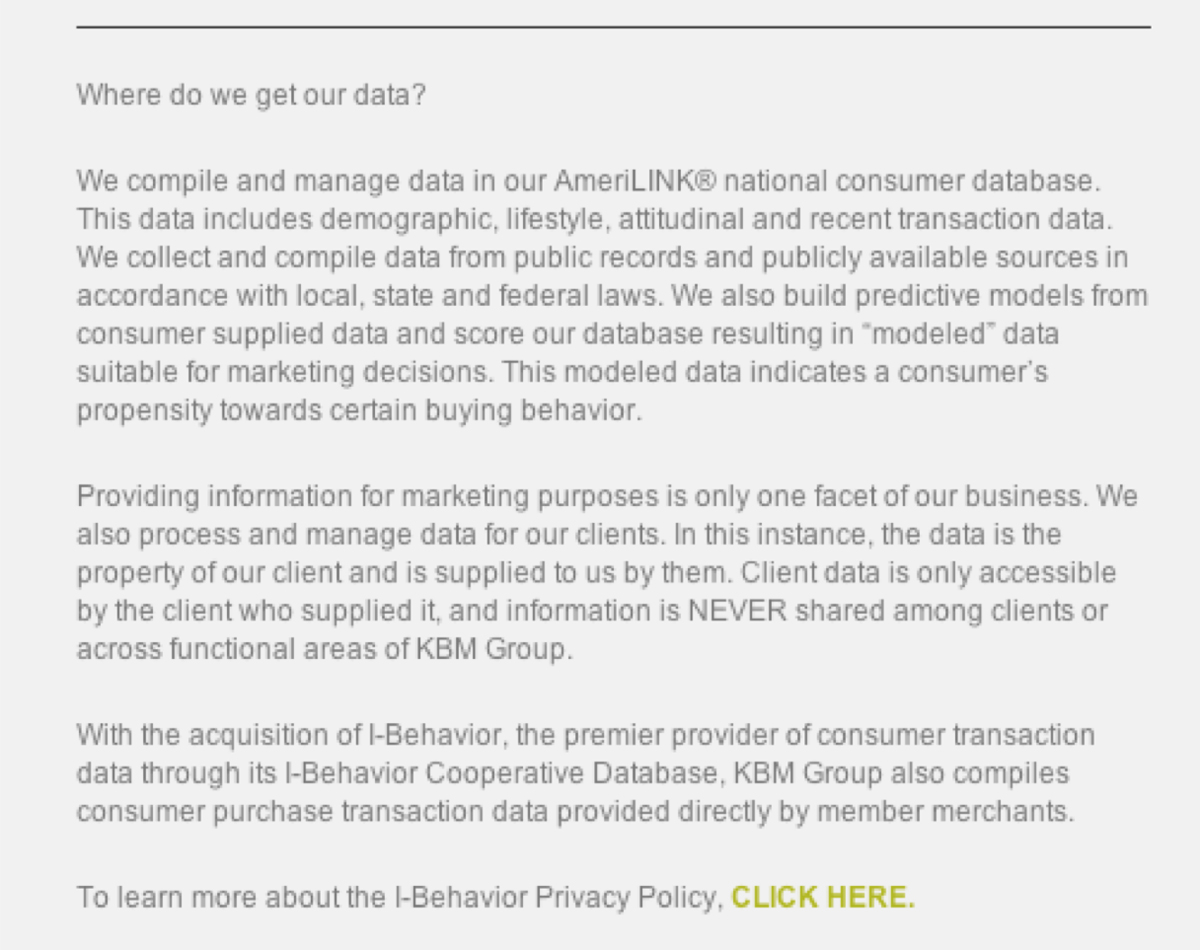

Of the sources, a disturbing source is retail purchases both online and off. Cooperative databases allow retailers to append copious data about consumers to retail transaction files. This is the basis of the Pineda vs. Williams Sonoma case in California which Williams Sonoma took a consumer’s email and added home address information. Below is an example of the use of retail transactional/cooperative databases, this one from KBM Group. [6]

Later in this testimony, I include this company as an exemplar of good opt out practices.

Sensitive Information and Lists That Should Not Exist

One of the key characteristics of modern data brokers is a lack of restraint. The degree to which no piece of data is sacred is evident in the reams of sensitive consumer data compiled, scored, circulated, and sold.

I do not oppose the selling of lists entirely. There is a reasonable center to be found. I agree that some lists are probably always going to exist that one or another person deems sensitive. Selling lists of doctors, nurses, teachers, and so forth are not among my favorite business models. But I understand the need for these lists and how they can be used in an unobjectionable way. I think of these lists as the center of the bell curve. These lists are of professional people.

However, some lists should not exist at all. This is where I urge Congress to take action. Highly sensitive data are the frayed and ugly ends of the bell curve of lists, far from the center. This is where lawmakers can work to remove unsafe, unfair, and overall just deplorable lists from circulation. There is no good policy reason why unsafe or unfair lists should exist.

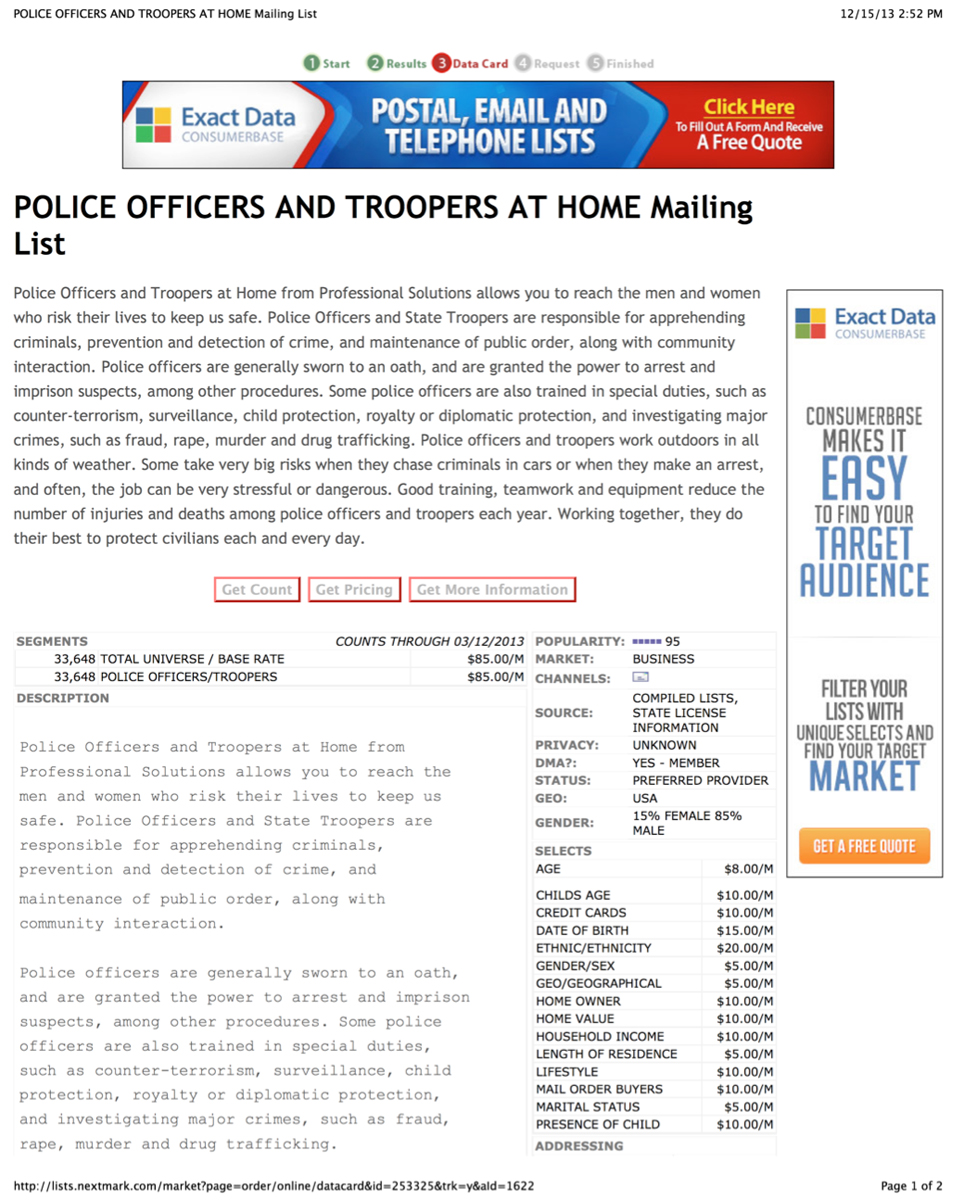

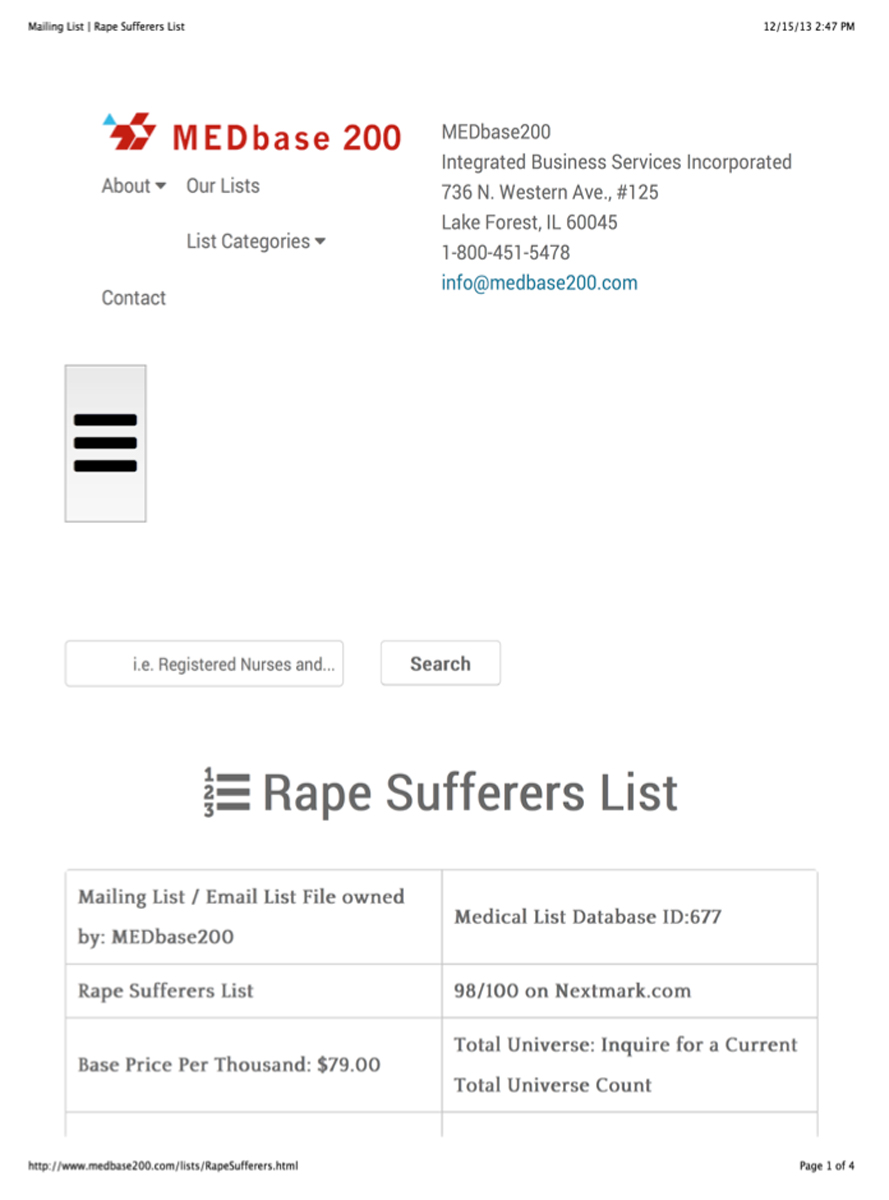

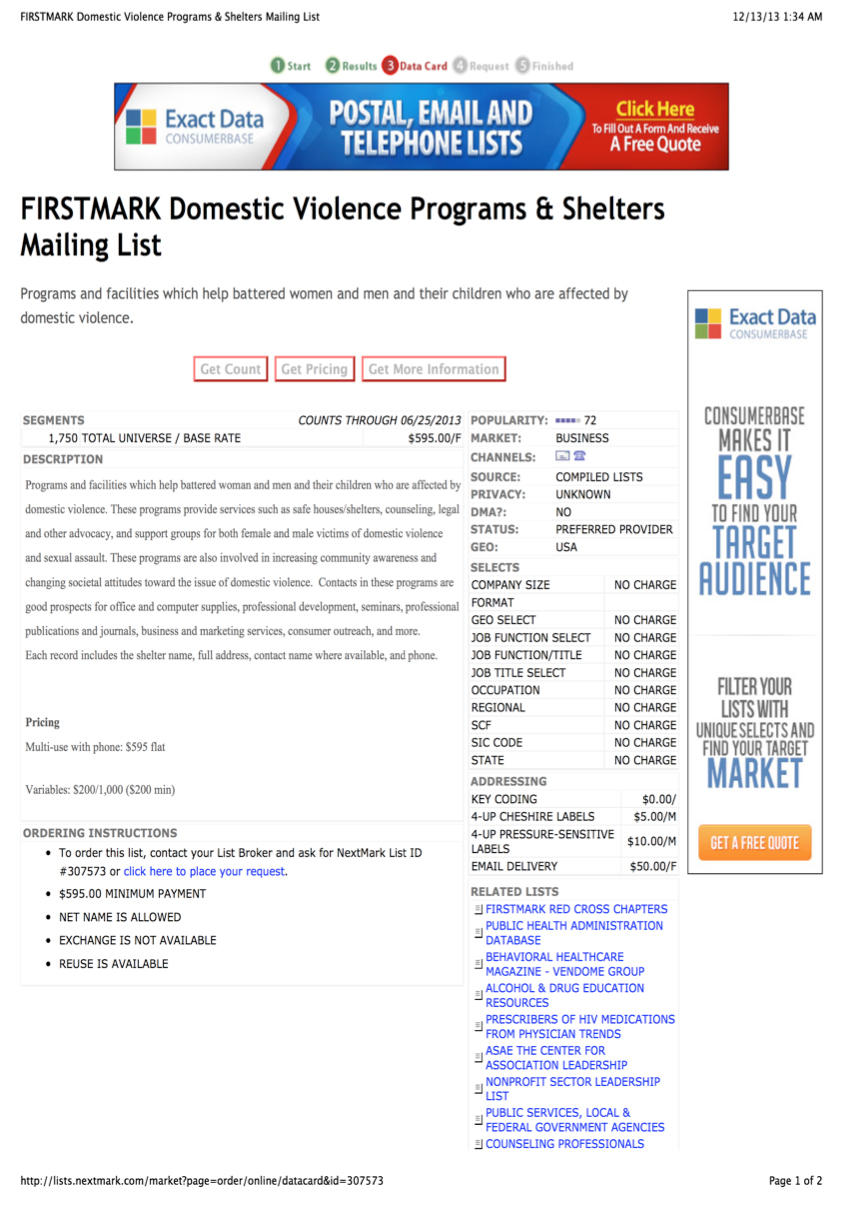

I give you some examples: police officers home addresses, rape sufferers, domestic violence shelters, genetic disease sufferers, among others, below:

– A list of police officers at home addresses. This list can threaten the safety of police officers and their families.

– A list of rape sufferers. This is an unjustifiable outrage that sacrifices a rape victim’s privacy for 7.9 cents per name.

— A list of domestic violence shelters. Existing laws allow domestic violence shelters to keep their location secret so that abusers cannot find their victims. The commercial sale of lists of these shelters is unjustifiable.

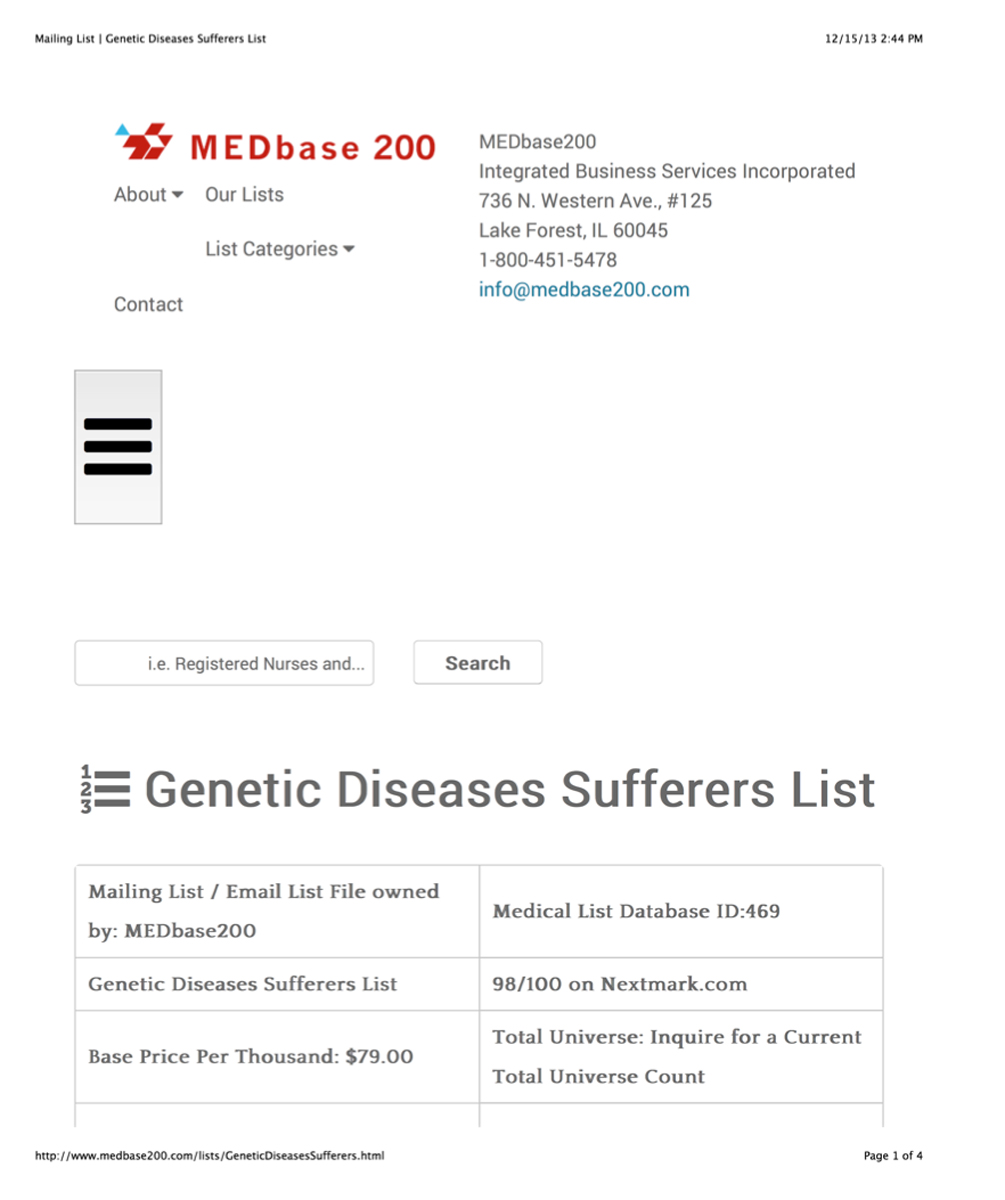

– A list of genetic disease sufferers. This list identifies people suffering from genetic diseases. This information will apply to these people — and their progeny — for their lifetime. Congress and the States have passed laws to protect the privacy of genetic information, but these laws do not stop data brokers from selling genetic information to anyone for any purpose.

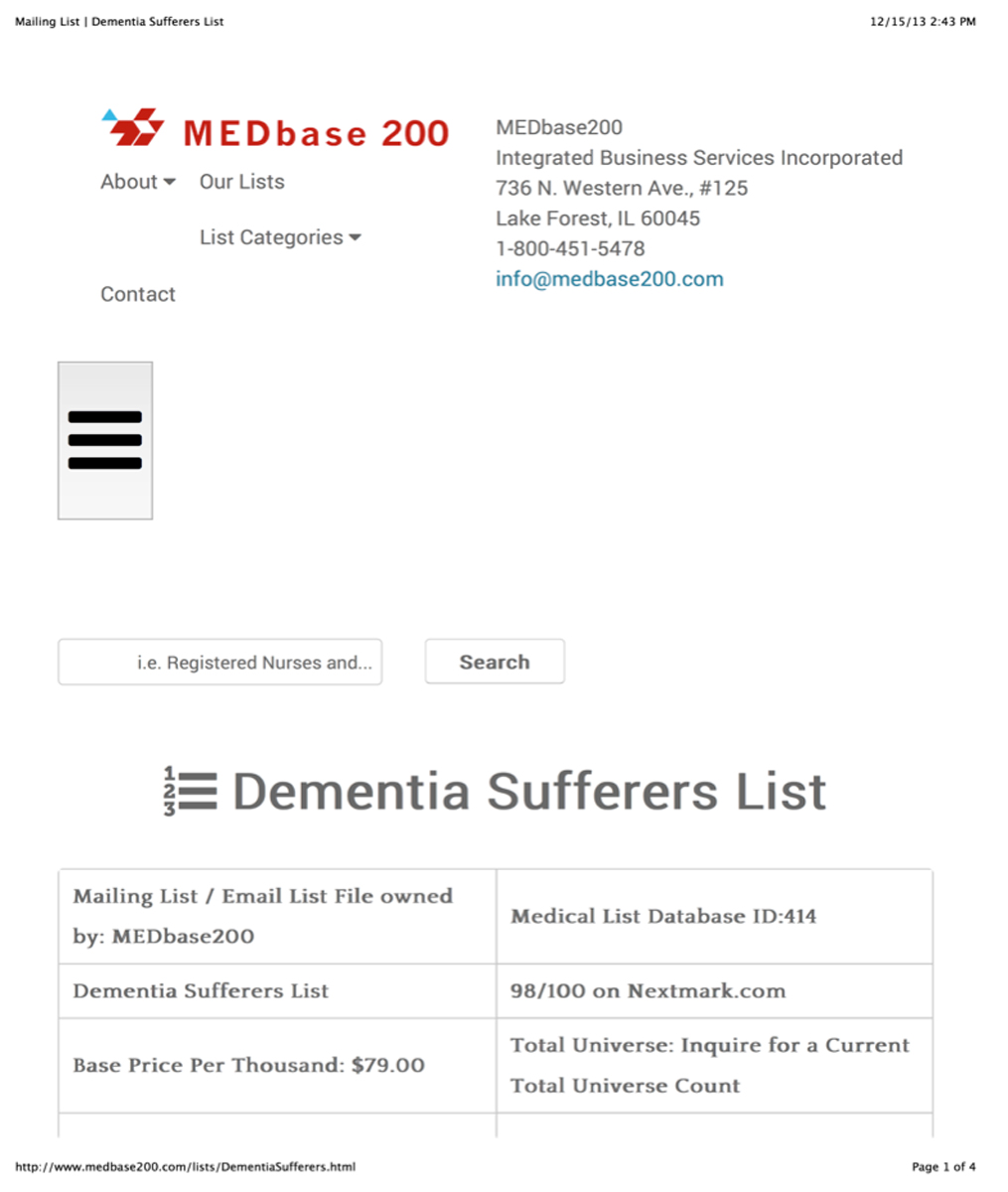

– A list of seniors who are currently suffering from dementia. These unfortunate people are often targeted for highly predatory offers. A list of caregivers would not have the same potential for deleterious consequences.

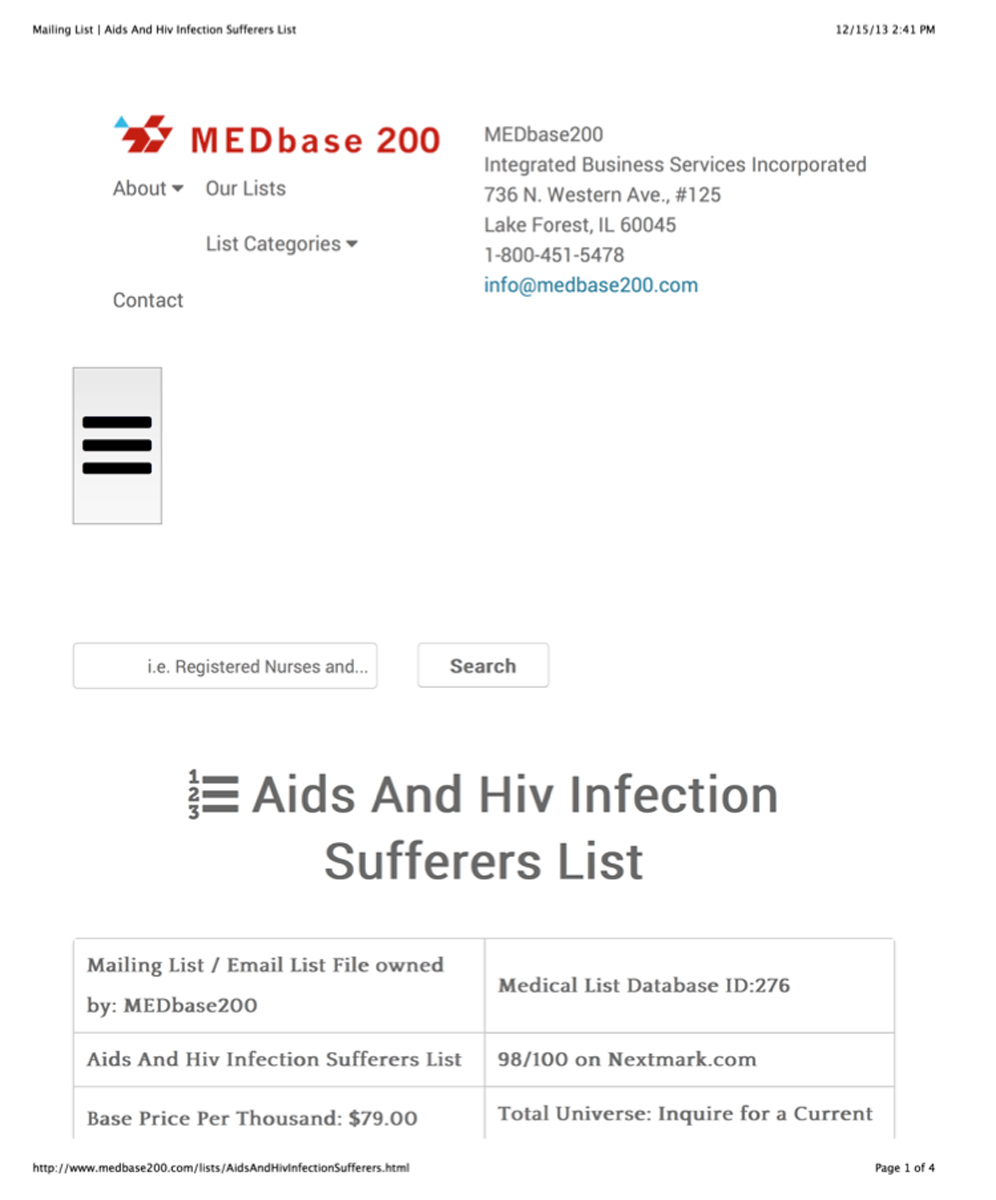

– A list of HIV/AIDs sufferers.

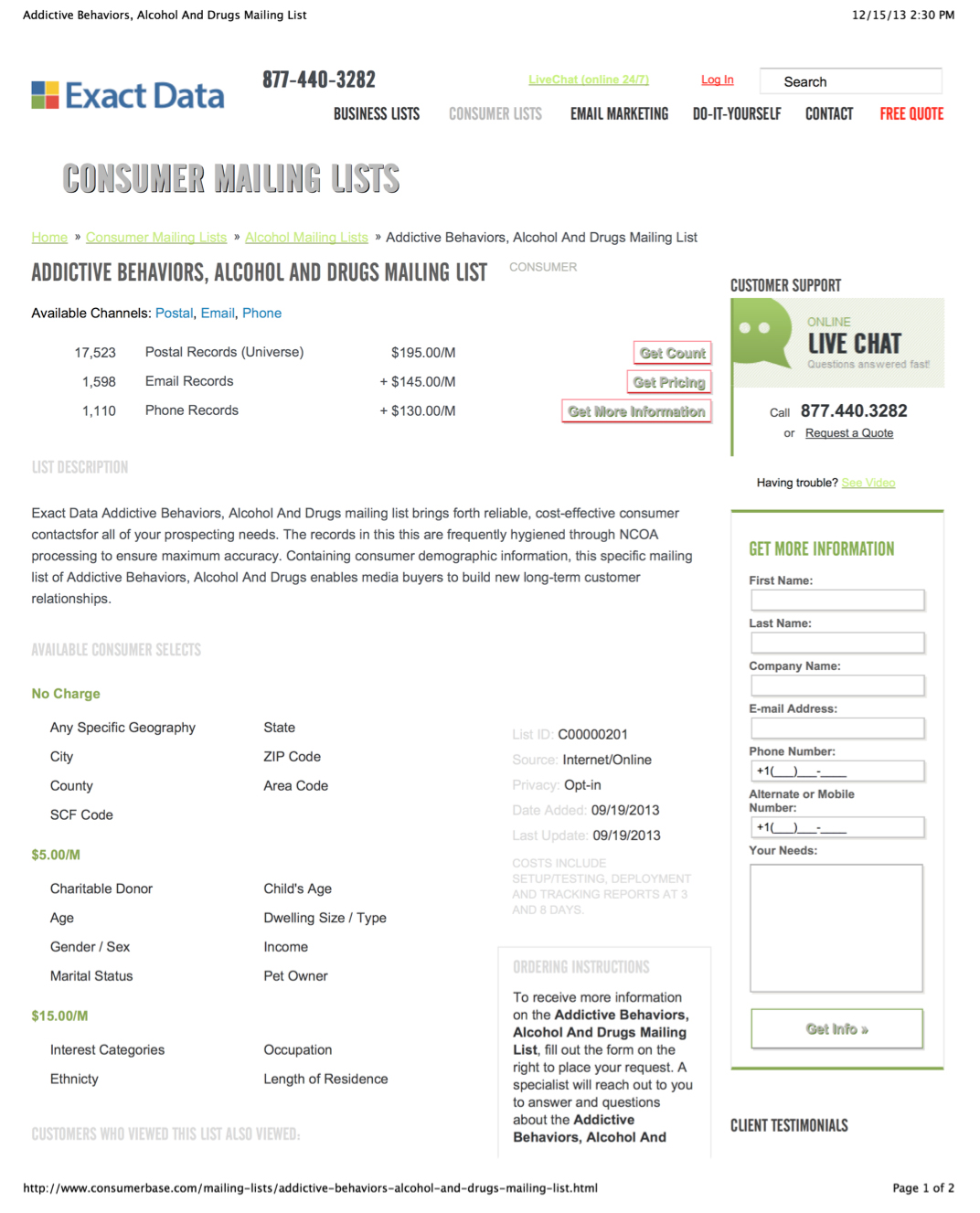

— A list of people with addictive behavior, alcohol and drugs. Alcohol and drug treatment information about patients is the subject of extra protections under existing law, but no law stops data brokers from profiting by selling the information.

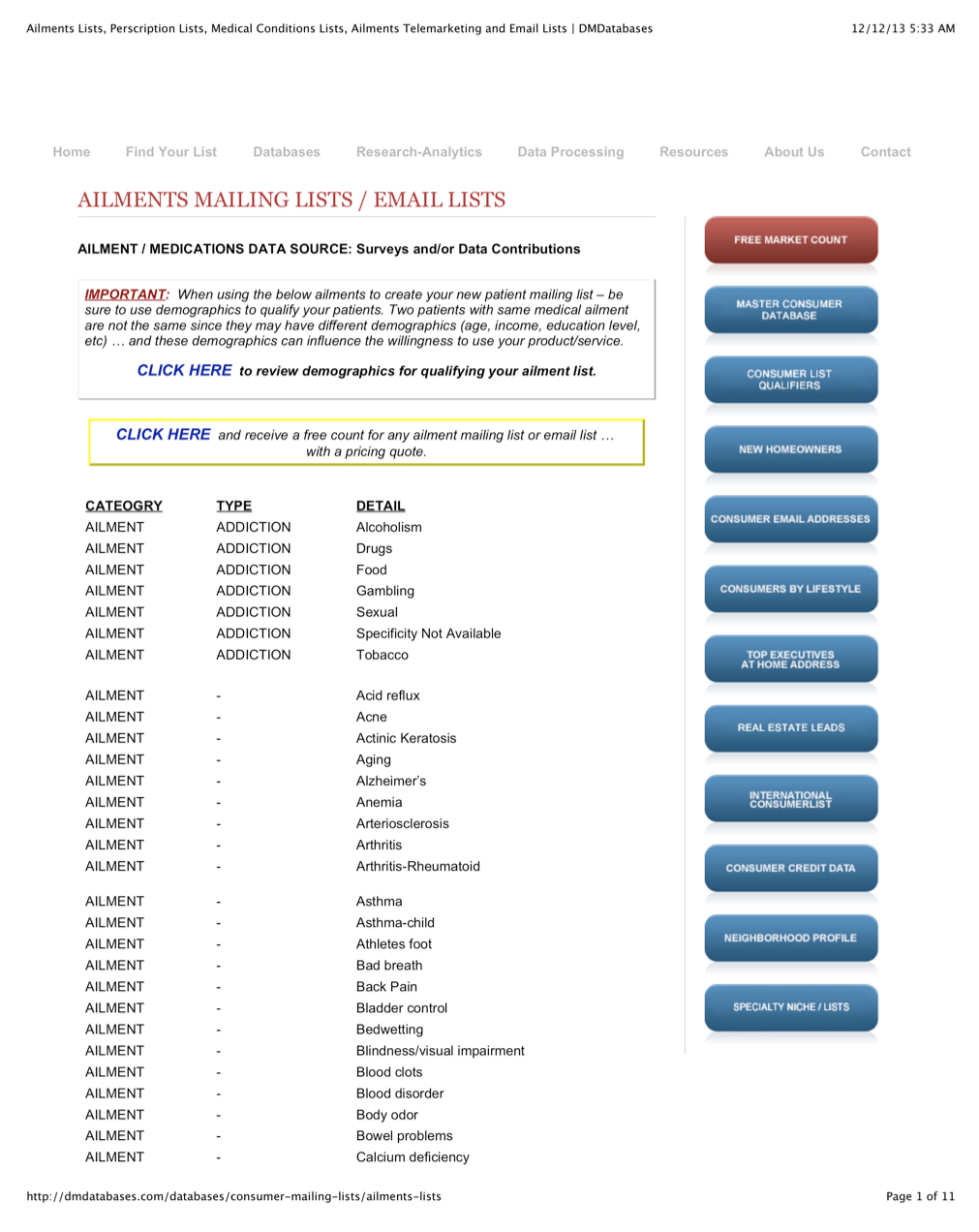

— A massive list of people identified by disease and prescription taken. Diseases include everything from A to Z, from cancer to mental illness, to bedwetting to gambling and much more.

These lists speak for themselves. Can we agree that some lists should not be circulated? Can we agree that the people named and pinpointed and targeted by these lists should be protected from the harm that can come from simply the inclusion on the list? I hope this is the case.

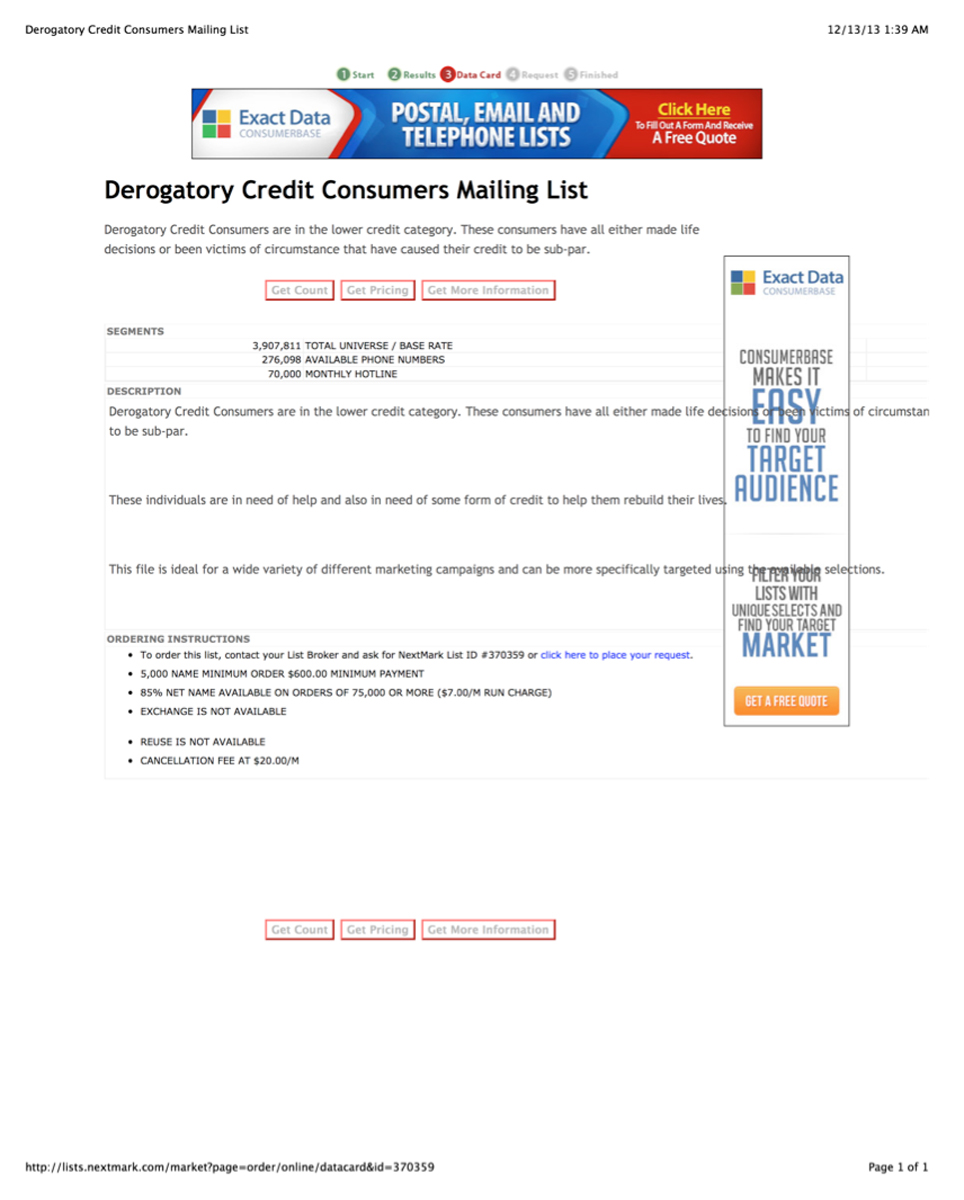

I also would put derogatory credit lists on the firing line for if not removal, then special treatment. These lists abound,

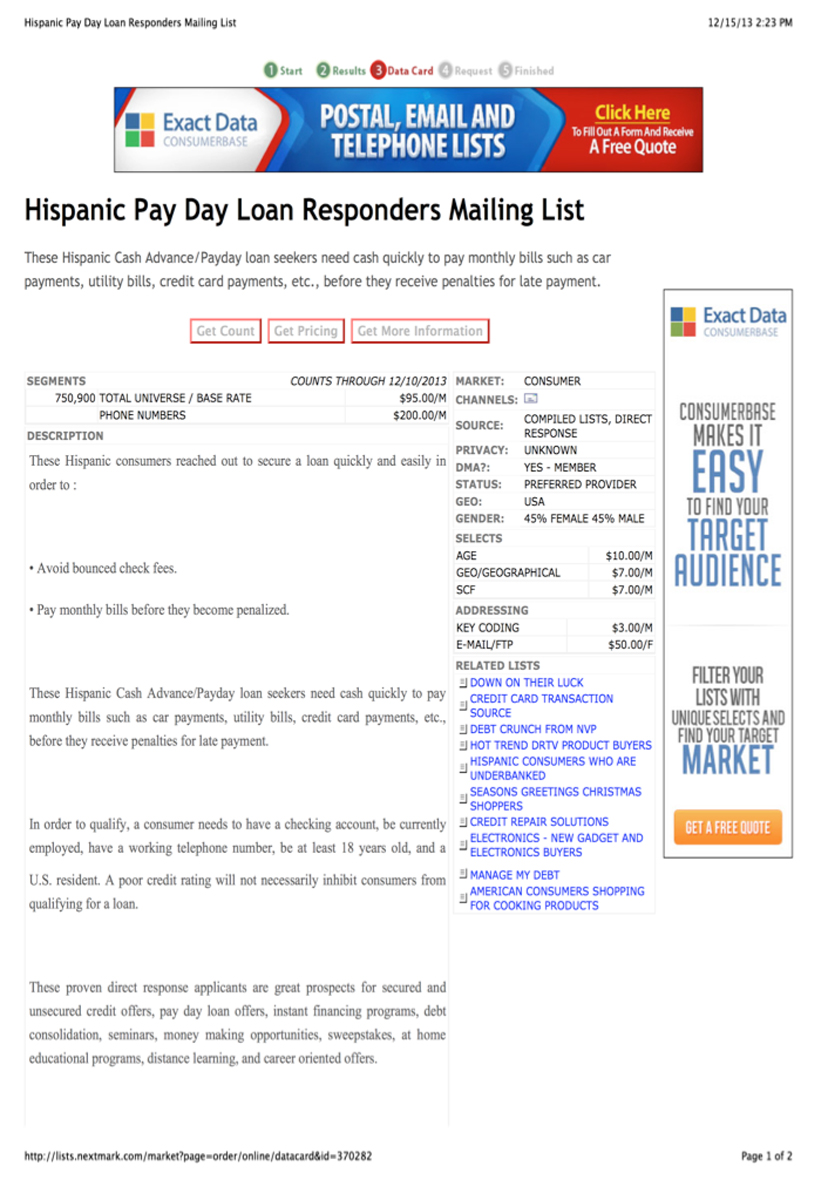

–Hispanic payday loan responders

– Derogatory credit consumers. These millions of consumers fall into a low credit category.

In the Solutions section of this testimony I discussion ways that this negative list situation can be improved. It is important to note that the lists are just the obvious outgrowth of other data broker activity, such as scoring.

Geography is Destiny: Trailer Parks and Zip+4

Where a person lives counts. A lot. Unfortunately, or fortunately, depending on where you live, geography is marketing destiny. And marketing destiny can now affect what opportunities come your way by virtue of savings, discounts, or receiving financial offers.

For example, people who either live in a trailer park or within a certain radius, usually a couple of miles of a trailer park, are often candidates for list suppression. They will not receive opportunities that their neighbors do solely because of their type of shelter. Or conversely, people who are in a trailer park may be specifically targeted for ads for low- income products or services. Is this trailer park redlining?

DMDatabases offers, for example, a suppression list that includes trailer parks as an option, among others:

OTHER SUPPRESSION OPTIONS

NURSING HOMES

TRAILER PARKS

MILITARY BASES

COLLEGE DORMORTORIES BANKRUPTCIES, TAX LIENS, JUDGEMENTS [7]

It can be reasonable and fair or a local business to use Zip + 4 to target a geographical area nearby. This makes a lot of sense. But I am not persuaded that it is fair to use detailed census tract data and Zip+4 to unfairly exclude people who may be living in or near the edge of poverty.

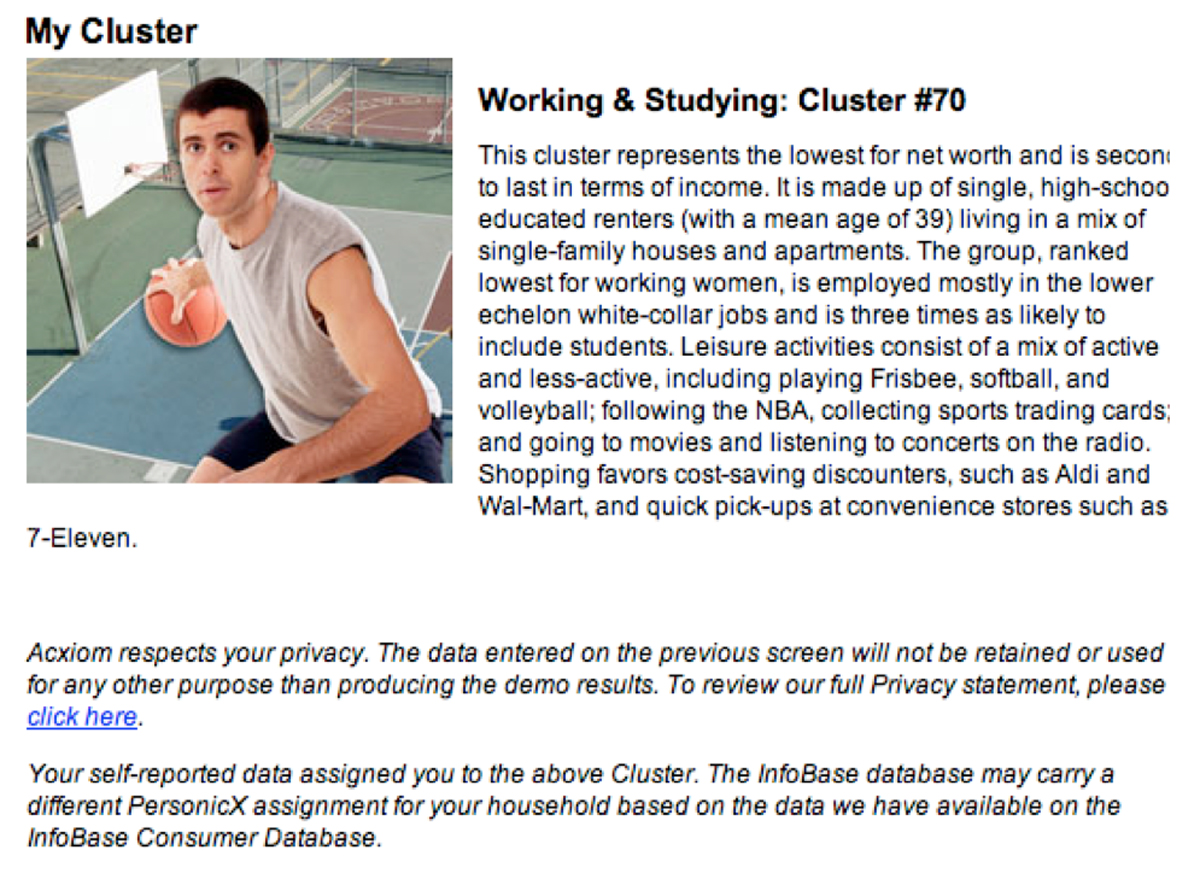

Inferences and Categorization

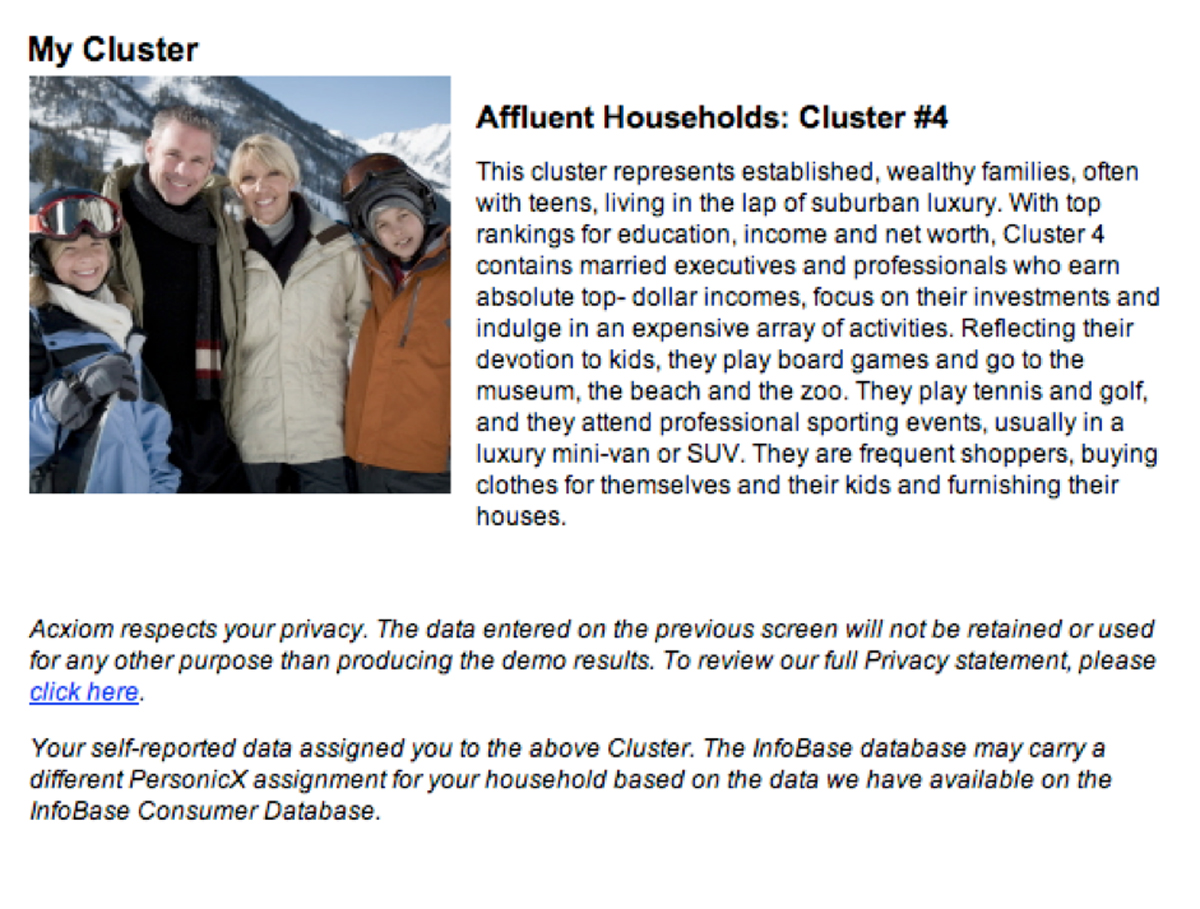

Data brokers categorize consumers into tightly defined boxes sourced by retail transactions, number of credit cards, ethnicity, marital status, gender, education, and many other factors, including neighborhood. There are a number of products sold by data brokers that accomplish this. One product in this category is Personix, sold by Acxiom. There are 70 Personix Clusters, each one identifying a type of consumer. Another product is Prizm, sold by Claritas. [8] “P$ycle” by Dataman Group [9] is another product. However, I do not know of a single company that allows consumers to view the clusters they are put in. I do not know of a single data broker that will allow consumers to permanently opt out of the cluster definitions attached to them.

At Acxiom’s It’s About The Data Portal, entering various zipcodes, salaries, and characteristics such as presence of child, marriage, and so forth allows one to explore the clusters.

Here are two sample Acxiom clusters:

These clusters come attached to average ages and proximal information to guide marketers. The clusters are purchased by other data brokers and are used to overlay other data they already have. In many ways, the clusters shape the ads we see online, the deals we get in the mail, and in some cases, unwanted targeting both at the high and low end of the clusters.

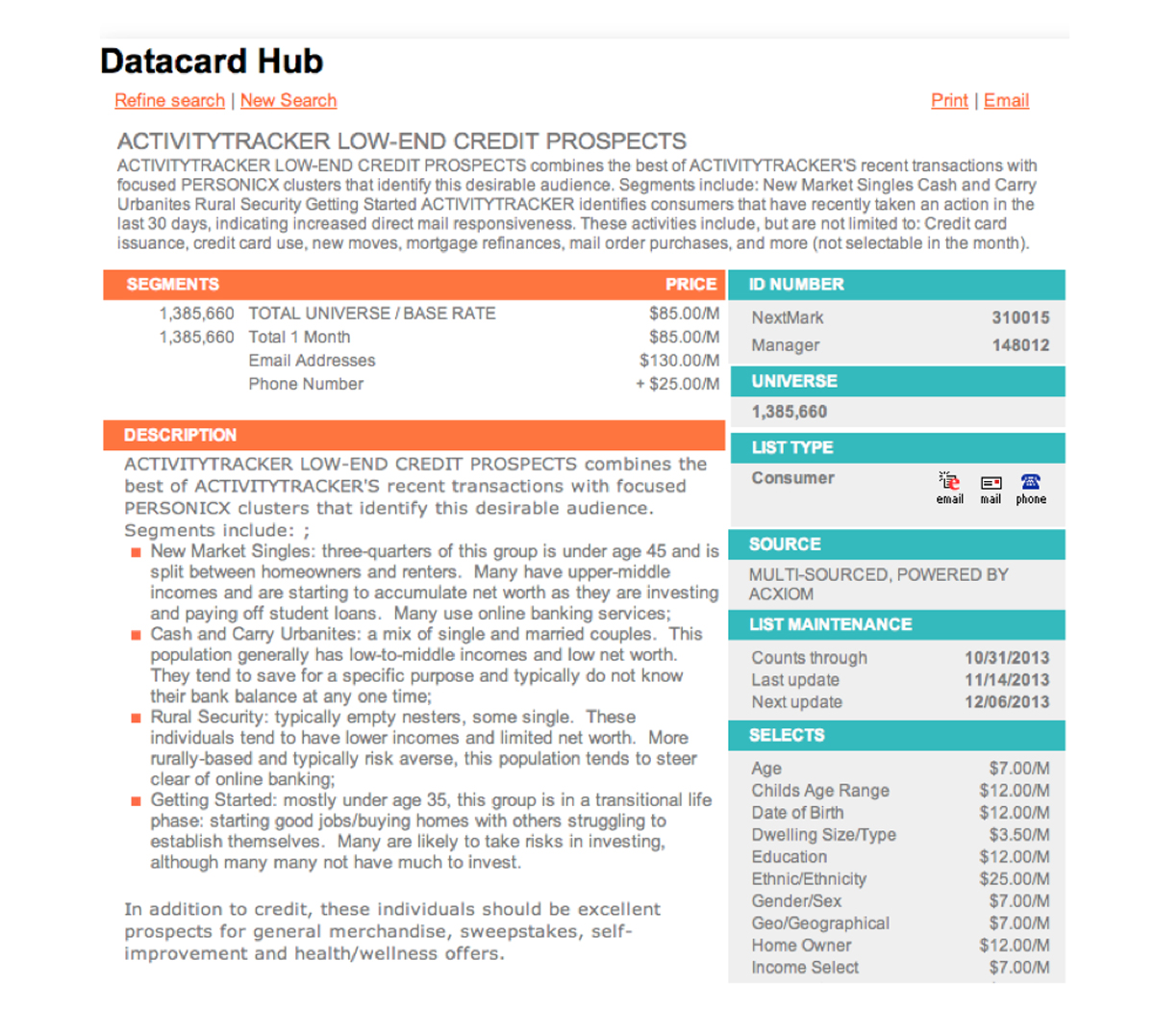

Take for example the following data card, which is described as Low End Credit Prospects. The source for the data is multi-source, and includes Acxiom data. The data card specifically identifies low-end credit prospects by their inclusion in the Acxiom Personixs clusters. In this case, these consumers were not described by being assigned a modeled credit score, rather, the cluster does the work of characterization. The category profiles are then combined with recent transactions, which in turn landed these consumers on this data broker list. [10]

What is most objectionable is that many products like Acxiom’s exist without consumers having any rights with respect to the data about themselves that is being compiled, bought, and sold. Errors may significantly alter the cluster a person is in, therefore altering the quality and type of offers a consumer receives. Life looks very different for cluster 1 and cluster 70.

Consumers need more rights over the use of their personal information by data brokers.

Modern Eligibility

Eligibility has expanded and, with it, the uses of marketing data for eligibility purposes and for suppression purposes. In the traditional credit world, the FCRA still regulates the use of credit in strictly-defined eligibility situations, such as employment and insurance. The Equal Credit Opportunity Act also places limits on data use. So does the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act’s (HIPAA) health privacy rule.

Modern eligibility has evaded, avoided, and overrun these laws, creating an unfair situation for consumers. When health data is held by a covered entity, HIPAA protections and rights apply. However, the exact same data, used for purposes outside of strictly-defined FCRA, ECOA or HIPAA limits and when not held by a health care provider, escape the bounds of regulation. The definition of eligibility needs to be expanded to encompass how data is now used. Consumers need more rights with respect to these activities:

• Authentication: using public and behavioral data to authenticate consumers to use a service.

• Anti-fraud: using transactional and behavioral data to determine whether fraud is occurring.

• Identity verification: Running quasi-background checks to verify aspects of a consumer’s identity.

• Lifestyle: Background checks for dating web sites, for schools, for clubs.

• Offers or suppression based on proxy credit scores: data broker-generated financial offers based on non-credit information, but just as accurate as a traditional credit score. Or the inverse: people are excluded from a list based on this information, but without associated FCRA or ECOA rights.

• Offers or suppressions based on medical data: Consumer health information that has escaped from the boundaries of HIPAA — a significant amount — needs new rules that data brokers must follow. Health-related analytics that have an impact on consumer’s health care prices, health care, credit, or employment need controls To protect consumers. Certain lists should not exist, and certain data should not be used in lists, in analytics, or anywhere. Even lists that data brokers deem non-sensitive such as lifestyle lists identifying smokers or other patterns need controls.

Consumers who fail authentication tests, ID verification, or get identified as a fraud risk will show up with different scores, will wind up on different consumer data broker lists, and may have difficulty conducting their daily business. Consumers who are painted as fraudsters may find themselves locked out of their own bank, credit cards, and even phones. Consumers who are identified as having very low or derogatory credit by non-traditional analysis and scoring may find themselves deluged with predatory offers. Consumers who are marked by a data broker as having cancer, previous trauma, a chronic disease, including genetic diseases, and even lifestyle markers, can have that data sold to the wrong party and find themselves on the short end of the health care stick and deeply stigmatized in many areas.

Circumventing the FCRA

While my testimony is not focused on the FCRA, it is important to state for the public record that many data brokers are engaging in behaviors that circumvent of the FCRA. I leave it to the Committee to decide if these activities are already illegal or if they should be brought within the FCRA and regulated in the same way as traditional credit records.

Proxy credit scores relate to circumventing the FCRA. [11] There is another issue related to circumventing the FCRA. Many of the web sites selling consumer background check data and other data state in a disclaimer that they are not a consumer reporting agency and therefore are not regulated under the FCRA. They adjure their customers to not violate the terms. The restrictions are not meaningful, and we suspect the violations of terms are routine.

There need to be meaningful checks and balances to keep improper uses from occurring. Given the sheer numbers of affiliate web sites selling consumer data, this will require some affiliate oversight and reform. We found some affiliates without a privacy policy, much less an opt out.

From http://www.peoplesearchnow.com/default.aspx:

Just because there is a paragraph stating that a web site is not operating as a consumer reporting agency doesn’t make it so. We strongly suspect that the disclaimed is offered with a wink, safe in the knowledge that no regulatory agency will be able to look at hundreds of small sites for violations of the law.

Data Broker Opt Out: The Grim Choices Consumers Face

Consumers face bad options and scant choice when it comes to data broker opt out. Leaving aside rights conferred under the FCRA for strict FCRA-defined eligibility purposes for the moment, consumers are in fact left largely to fend for themselves with few tools and no clear rights. Some opt outs exist, but the landscape is difficult — so much so that it is improbable that consumers can wend their way through the opt out process successfully.

How many allow opt out?

The World Privacy Forum compiled a list of 352 consumer-focused data broker sites and lists. Our list is available at https://www.worldprivacyforum.org/2013/12/data-brokers-opt-out/. A study of the data broker industry conducted by Dr. John Deighton for the Direct Marketing Association in 2013 found that the universe of data brokers was approximately 3,500. [12] Our data broker list, then, comprises at ten-percent rough sample of this universe. Included on the list are various people finder web sites, data brokers that this Committee or the FTC has sent letters of inquiry to, consumer list brokers, and others. Of 352, 128 offered a data opt out. Some of those were full opt outs, some partial or unclear, some of them cost as much as $1,799.00, and one opt out promised that the site reserved the right to “publish the request” if someone decided to opt out.

Opting out of Data Broker Scores and Lists

To remove a consumer’s name and information from all data broker lists appears to be an almost impossible task right now. If a mailing list is held by a DMA member, the DMA opt out can be effective. However, not every data broker is a DMA member, which poses an immediate problem. For scores, there is no known score opt out. After a consumer is assigned a score by a data broker, a consumer will find it nearly impossible to find that score or to opt- out of its use to describe or characterize the consumer.

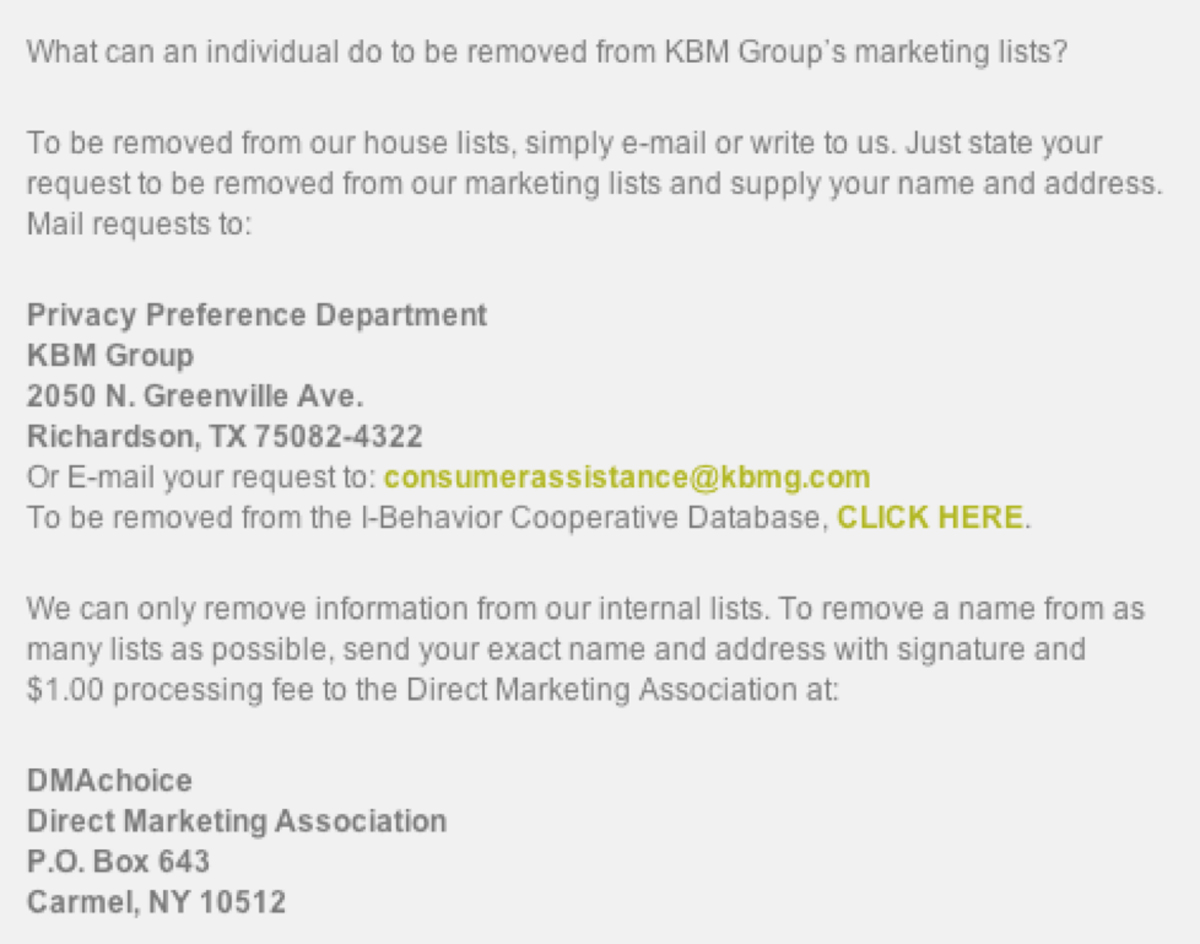

In our research, we have found one exemplar company that is allowing an opt out of their databases and lists, KBM Group. A screen shot of the relevant portion of the policy is below; note that the policy allows for internal database opt out as well as linking to the DMA opt out. The policy is located at http://www.kbmg.com/privacy-policy/. This is a best practice, and is seldom seen.

Suppression vs opt out

It is important to note that when consumers opt out of data broker web sites or lists, most often what is happening is that their information is being suppressed. The information remains, but it is removed from circulation. Delete is not a word that is used very often in data broker opt out.

For consumers who want to get off of data brokers marketing lists, the primary mechanism for removal is to use the DMA Choice opt-out mechanism. This will put the consumer on a suppression list, which means the data brokers will still have the consumer information, but no further sales or marketing will occur within a given time frame via the lists that allow opt out or suppression.

When data brokers allow for a DMA Choice opt out to influence all of their list and brokering activity, this is a good thing. But this is not nearly as common as it needs to be. Only some lists adhere to the DMA Choice program. One significant problem is that not all data brokers are DMA members, and thus escape the self-regulatory program. For those that are DMA members, we do not know how effective the DMA Choice program is.

Policy Issues in Current Opt Out/ Suppression Practices

Of data brokers that allow opt out, additional policy issues include the following:

• Incomplete: Most opt outs are incomplete, and often require consumers to have a safety reason for the opt out.

• Suppression not deletion. Many opt outs are suppression-based. This may be difficult to change.

• No Third Parties: Consumers are usually required to ask for the opt out directly on their own. Requests through third parties are not allowed. This makes opt out an impossible proposition for consumers, who have to go to each individual site to effectuate the opt outs that are available to them. It is clear that the policy deliberately seeks to make it as hard as possible for consumers to exercise the ability to opt-out.

• No Guarantee: An opt out is not guaranteed, no matter why the consumer is conducting the opt out. Thus, the opt out may not work or may only be effective for a short period of time.

• Fees: Some data brokers charge fees ranging from annoying (less than $30) to exorbitant (in excess of $1,000).

• Hunting for the opt out: Finding the opt outs on many consumer data broker sites is an exercise in extreme patience and persistence. Opt outs are seldom indicated by a prominent opt out button labeled as such. While some data brokers do play nicely with consumers and provide this, fair play is the exception, not the rule. Typically, opt outs are buried deep within a privacy policy, terms of use, or FAQ.

• Opt out requirements non-standardized: Opt out requirements non-standardized: A bewildering array of choices face the person who wants to opt out of data broker lists. Some opt outs are fair. DMA Choice is a reasonable opt out. But many are not reasonable or fair. Some require a privacy-concerned consumer to send a scanned copy of a driver’s license or to jump through other hoops. We would be reluctant to recommend that a consumer share a copy of a driver’s license. Many consumers do not have a driver’s license or other government-issued form of identification, and these consumers may find it impossible to opt out.

• Marketing use of opt -out information: No regulation stops data brokers from selling or otherwise using the information given in an opt out application.

• Negotiating the opt out: There is no controlling legal standard for data broker opt out. As a result, consumers have to dig through complex privacy policies and language and figure out each opt out.

• Partial Opt Outs Only: Some data brokers allow for partial opt outs, meaning that it is available only if there is a safety issue, or if an individual is a member of law enforcement. However, there are concerns even with this. There are no rules that say that information about the request to opt out will not be sold or shared.

• No opt out: Many data brokers do not allow any opt out. Consumers are left with no recourse.

Examples of challenging opt outs

Here is an example of a privacy policy with an opt out notice, this is from a consumer-facing data broker site called SortedbyName.com. Note the last sentence, where consumers who opt out may be treated punitively for doing so (emphasis in italics is mine).:

• This webmaster reviews stats, including IP addresses of site visitors from time to time.

• Third party vendors, including Google, use cookies and web beacons to serve ads based on a user’s prior visits to the website.

• Google’s use of the DART cookie enables it and its partners to serve ads to users based on their visit to the site and/or other sites on the Internet.

• Users may opt out of the use of the DART cookie by visiting the advertising opt-out page. (You can opt out of a third-party vendor’s use of cookies by visiting the Network Advertising Initiative opt-out page.)

• With the Firefox browser, use Ctrl+Shift+P for private browsing. Use Tools – Options – Privacy to set preferences. Use Shift+Ctrl+Delete to clear your history so remote servers cannot access it.

•By sending a request for removal of names from the site, you give us permission to publish the request, including your email address and all headers. [13]

Here is an example of a complicated opt out, this at from waatp.com:

How do I remove or update my data on waatp.com?

waatp.com investigates for live data reached by public on a regular basis. Because this information is

not contented on our hosting, we cannot give any guarantees these data will be

removed until the

change has been occurred at the source of the data. To update or remove this

information, we advise:

Our site will provide the certain source for the information the applier would have

changed or

removed. Approval that applier is the individual specified in the Public Profile is an

obligatory

condition, therefore we may ask that appliers faxes or emails it:

1 – a written application asking for the database source or a change application;

2 – a screenshot of a page, with marked information that you ask to change or to search in the

source;

3 – a legal proof of ID like State/Federal ID card that points your name, full address,

date of birth

(you can remove your personal photo an/or ID#);

4 – any pseudonyms;

5 – ex-addresses, including str.name, town, zip.

You should fax this information to 800 861 9713 (please attach an e-mail so that we are able to

contact you regarding any questions) or e-mail to Profile-Remove /at/

waatp.com.com. Changes might

take up to 6 weeks to come into effect and are only constant if the info has been

previously edited

or removed at the original source. Without a constant change at the original source,

the process of

deletion of any info stored in a Public Profile is NOT guaranteed. [14]

An example of the No third Party policy can be found at People Smart,

The Scoring of Americans

Americans face a future that is increasingly being shaped in significant ways by their consumer scores. A consumer score provides a way of evaluating an individual or a household. The best-known consumer scoring activity is credit scoring. Credit scores date back to the 1950s, and replaced human judgment about credit granting by relying on standardized criteria. While most people are familiar with credit scoring, consumer scoring encompasses a broader category of activities that uses scores to assess consumers for one or more purposes.

The World Privacy Forum offers consumer scoring as a generic term for these scoring methods. A consumer score derives from an algorithm that typically employs objective criteria. The score relies on demographic, health, consumption, transactional data, marketing, credit, or other personal characteristics. Companies and governments use the resulting score to make a decision about an individual or household.

By itself, consumer scoring is not necessarily good or bad. Scoring orders a population along a mathematically defined scale. However, scoring has the prospect of being used to affect individuals in significant ways that may not be fair. If a score becomes the way that consumers are treated, then the results may not be acceptable to the American public. The quality and relevance of the data used, the transparency of the methodology, and the reasonableness of the application are the major factors that determine the fairness of any scoring activity. These issues are likely to be the central focus on the policy debate about consumer scoring.

Consumer scoring is already more widespread than most people realize. A significant segment of the data broker industry already focuses on scoring and predictive analytics, and as such, is intricately interwoven into the scoring business. [15] Known consumer scoring activities include assessments and predictions relating to insurance, bankruptcy, identity, fraud, consumption, health, propensity to purchase, “consumer value estimation,” and more. A dozen categories of consumer scoring have been identified so far, each containing numerous scores. There may be hundreds or thousands of consumer scores already in use. The federal government uses scoring for some purposes, an activity beyond the scope of this testimony but something that may be worthy of more attention by the Congress. It might be useful, for example, to ask the Government Accountability Office to identify all of the consumer scoring used by federal agencies.

The use of consumer scoring is expanding rapidly because scores provide an easy analytics shorthand for measuring consumer behavior, risk, and potential for future success or spending. Companies and government will use scores to make more decisions about a consumer’s access to markets, price for goods and services, ability to travel, and other social and economic opportunities. Schools will use scores beyond academic measurement scores to determine the viability of candidates.

Policy issues around consumer scoring

Secrecy

Most consumer scores today are secret — consumers cannot see most scores even if they know about them. Beyond the numeric value of the scores themselves, a complete lack of transparency surrounds consumer scores. Citing proprietary claims, the factors that make up consumer scores are secret. The procedures and algorithms are secret. Often, even the full numeric range and context are secret.

Credit scores were unknown to most consumers through the 50s, 60s, 70s, and 80s. Trickles of a score that was not disclosed to consumers but that could be used to deny a person credit began to leak out slowly to some policymakers, particularly around the time ECOA passed. In May 1990, the Federal Trade Commission wrote commentary indicating that risk scores (credit scores) did not have to be made available to consumers. But when scoring began to be used for mortgage lending in the mid 90s, [16] many consumers finally began hearing about a “credit score,” most of them for the first time, and mostly when they were being turned down for a loan. [17] A slow roar over the secrecy and opacity of the credit score began to build.

By the late 90s, the secrecy of credit scores and the fact that people could not see the underlying methodology or factors that went into the score or the range of the score to determine how the number should be interpreted was a full-blown policy issue. Beginning in 2000, a rapid-fire series of events — particularly the passage of legislation in California that required disclosure of credit scores — eventually dismantled credit score secrecy and non- disclosure. Now, credit scores must be disclosed to consumers, and the context, range, and key factors are now known. [18]

Credit scores are no longer secret, and this was and still is the right policy decision. Why are other scores secret, when they are being used for important decisions about consumers? Why are other score factors and numeric ranges secret, when the risk of marketing data comprising the score of a factor used in modern eligibility practices is very high?

There should be no secret scores, and no hidden factors.

Unfairness

Of significant concern regarding scoring are the factors that go into the creation of a score. A single score is often created from the admixture of more than 600 to 1,000 individual factors. These factors can include race, religion, age, gender, household income, zip code, presence of medical conditions, zip code + 4, transactional data from retailers, and hundreds more. Therefore, one individual score can contain hidden factors that range from non-sensitive to quite sensitive. A score that is designed to assess or assign consumer value to a business could also include factors that would be entirely unacceptable or that, in the context of either the Equal Credit Opportunity Act (ECOA) or the Fair Credit Reporting Act, would be flatly illegal.

In a description of its sets of scores that can be purchased, one company described how it creates its scores:

Aspects Life Choices system

Our Database at the Core

Our proprietary set of data that allows us to produce powerful scored solutions. It is created from over 100 sources, updated quarterly, and contains 1,500 proprietary demographic, psychographic, attitudinal, econometric and summarized credit attributes.

Clear Benefits to Users

• Can be used to enhance any list

• Applied at the Zip+4 level

• Data can be custom modeled [19]

This particular company, like most companies selling consumer scores, does not publish its 100 sources nor its 1,500 attributes that it is using to develop the score for consumers’ perusal, nor does it summarize even the categories of information used for consumers. It is unlikely that consumers can purchase or see these scores for themselves, [20] and like other consumer scores, this score is opaque. If ECOA factors are present, no one but the company employees would know.

Notably, the ECOA requires that credit scoring systems may not use race, sex, marital status, religion, or national origin as factors comprising the score. The law provides the opportunity for creditors to use age, however, also requires that seniors are treated equally. [21] Marital status is commonly used as a consumer score factor, as are other factors either directly or inferentially connected to factors that would be protected under ECOA but are not in broader consumer scores, even if those scores are being used for other eligibility decisions.

Lack of Rights in Consumer Scoring

After a consumer has been scored, the factors (behaviors, characteristics, etc.) that went into the score do not typically disappear. After the score have been recorded into a data broker’s host database, there is not a way for consumers to remove themselves from this activity. A discussion of how this impacts proxy credit scores is below.

Exemplar: Modeled Credit Scores

The privilege of marketing information based on credit report data comes with the requirement that consumers can opt out of that marketing. Marketing targeted to credit reports is strictly limited to credit and insurance. [22] But analytics are at such a sophisticated level now that accurate “modeled credit scores” are being created and used as a proxy for traditional credit scores. These modeled scores are made of consumer information drawn from beyond the traditional credit bureau score to create an entirely new score. Because these scores contain no direct credit information, they are seen by some as outside of either ECOA or the FCRA. Therefore, information closely mimicking credit data is now being used for broad marketing purposes, and there is no requirement for opt out.

A good modeled credit score predicts financial risk comparable to the traditional credit score. Fair Isaac’s Expansion Score draws consumer information from non-traditional sources, that is, sources other than the big three credit bureaus. Although Fair Isaac does not disclose its data sources except directly to the individual consumer being scored, industry publications state that Fair Isaac is using deposit account records and pay-day loan cashing as predictive factors in its Expansion Score. [23] The Expansion Score is regulated, so consumers who have an Expansion Score are entitled to knowing certain information about that score, including the factors. Fair Isaac is playing by the rules, but data broker data cards indicate that not all companies (or data brokers) are when it comes to inferred credit data or scores.

Companies can now build score cards with very little or even no data by taking advantage of the new generic credit bureau scores to create a baseline of information. In these cases, the score card is typically monitored and evaluated closely to see if it is viable. [24] In this way, the equivalent of consumer credit scores that would be otherwise regulated under the FCRA end up being used for all sorts of purposes that would not be allowed had they been traditional credit scores. The end score could be something like a churn score, or customer loyalty score. In other situations, behavioral clues allow people to be targeted just as precisely as if their scores were known.

People, for example, who have a low Beacon score (an Equifax credit score) and are subsequently turned down for the purchase of a phone, show up on a data broker mailing list called “Cell Phone Turndowns.” [25] The data card says: “These consumers are ready and eager to receive offers and opportunities in the following categories: secured and sub-prime credit, Internet, legal and financial service, health insurance offers, home equity loans, money making opportunities, and pre-approved credit with a catalog purchase.” The Beacon score is not given — it does not need to be in order for data brokers to infer the credit score of these individuals. If a generalized credit score is known with certainty, as it is in this case, then why is it OK to then sell this information without limiting the data to FCRA constraints?

The use of the modeled credit score is well understood by data brokers. DMDatabases wrote this on its web site, discussing its modeled credit score:

IMPORTANT NOTE: The Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA) does NOT allow the release of actual credit data to any party that lacks a permissible purpose, such as the evaluation of an application for a loan, credit, service, or employment. Before requesting information on a credit score mailing list or credit score email list, make sure your offer is in compliance with FCRA guidelines. For details on FCRA compliance requirements – CLICK HERE.

GOOD NEWS / BAD NEWS: The bad news is that 90+ percent of offers do not meet the strict FCRA compliance requirements for using actual credit score data. The good news is that marketers have a very effective alternative … The Premier Modeled Credit Score Database.- CLICK HERE and read more..[26]

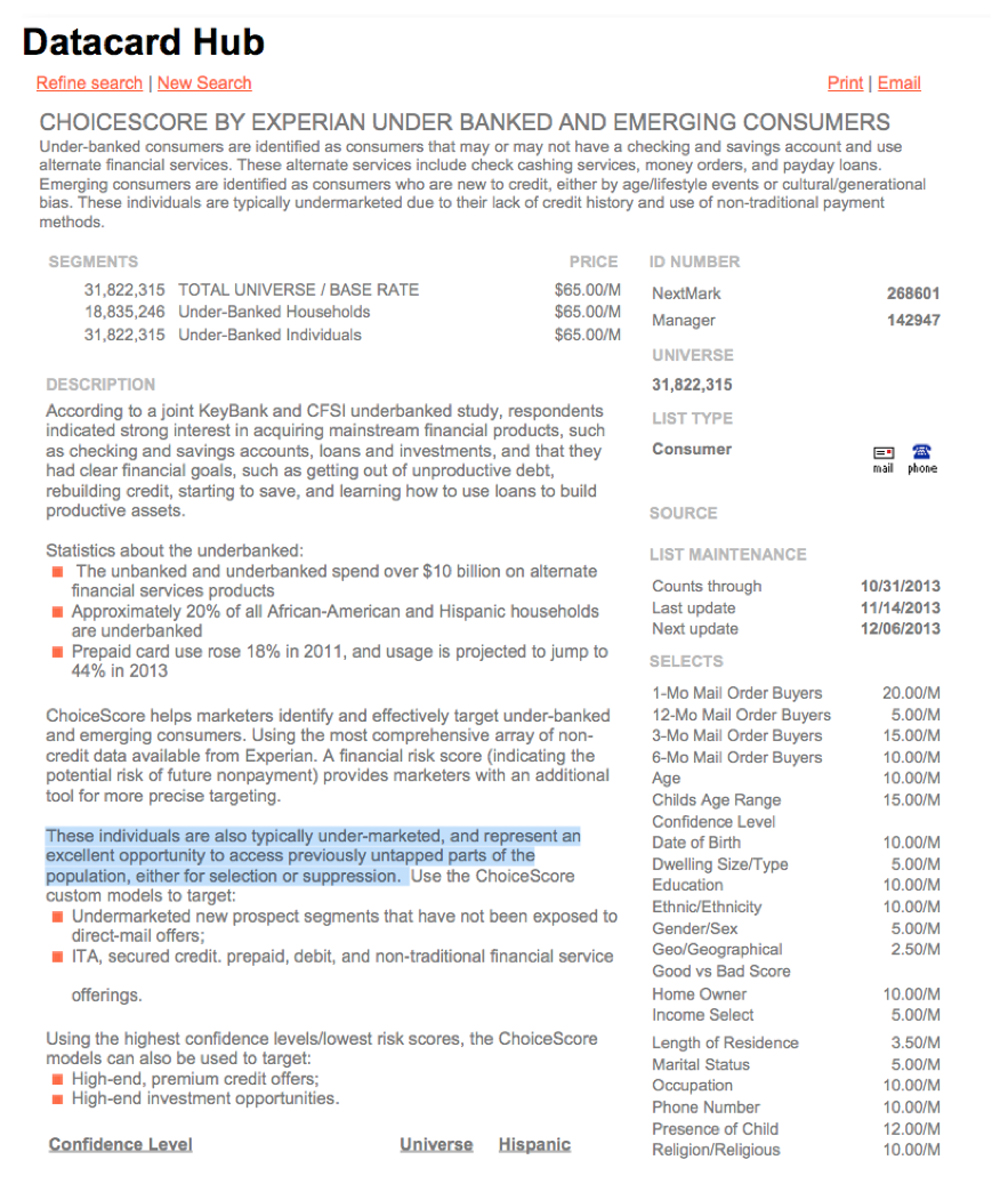

Experian sells ChoiceScore, a financial risk score built entirely of non-credit factors. [27] Experian explains in its description of the score that it is created from consumer demographic, behavioral, and geo-demographic information. One data broker selling a list of consumers who had been segmented by the ChoiceScore said this in its data card description, which can be seen in the screen shot below: [28]

ChoiceScore by Experian UnderBanked and Emerging Consumers

ChoiceScore helps marketers identify and effectively target under-banked and emerging consumers. Using the most comprehensive array of non-credit data available from Experian. A financial risk score (indicating the potential risk of future nonpayment) provides marketers with an additional tool for more precise targeting. [29] The data card also indicated that the ChoiceScore could be used to suppress some consumers from getting information.

Based on Experian’s web site, it appears that the ChoiceScore is apparently not available for sale to consumers. The score appears to be available for non-FCRA uses. [30] What factors go into these and other scores? How is ChoiceScore used in eligibility decisions? The score’s factors are not defined, so it is difficult to know what kind of marketing data is included, if at all, in the score. It is also difficult if not impossible to determine how or if or when the score is being used in modern eligibility decisions.

Are credit factors bundled into any base scores? Are credit factors used for non-credit marketing? Are any ECOA factors in the scores? How are credit and ECOA factors weightedin the algorithms? We do not know.

Modern data analytics have made child’s play of mimicking traditional credit scores and unearthing people who are in various credit score brackets. Congress acted to protect the use of this information with good reason. The change in technologies that give us new modeled scores of great accuracy does not change the underlying principles that still need to be at work here: fairness, accuracy, transparency, and some reasonable limits in use.

My question is this: if a modeled credit score is as good as a traditional credit score, shouldn’t it come under the FCRA? I believe the answer to this is yes. Congress needs to draw a bright line around this issue in particular and ensure that for fairness reasons it does not get entrenched any further. I predict that when consumers learn of data broker activity in the scoring area, they will not be happy.

Exemplar: Heath Scores

Another category to consider is the area of health. Health scores are now in circulation, which brings concerns, not the least of which is that consumers care deeply about their health privacy and decisions made about them regarding their health, insurance policy pricing, and prescription pricing. The same questions raised above about transparency, secrecy, factors, and use are relevant here. Other questions come into play as well. For example: can employers purchase health scores? Are health scores shared with debt collectors? Of note in the area of health and in other areas is the issue that companies increasingly either

Frailty Scores

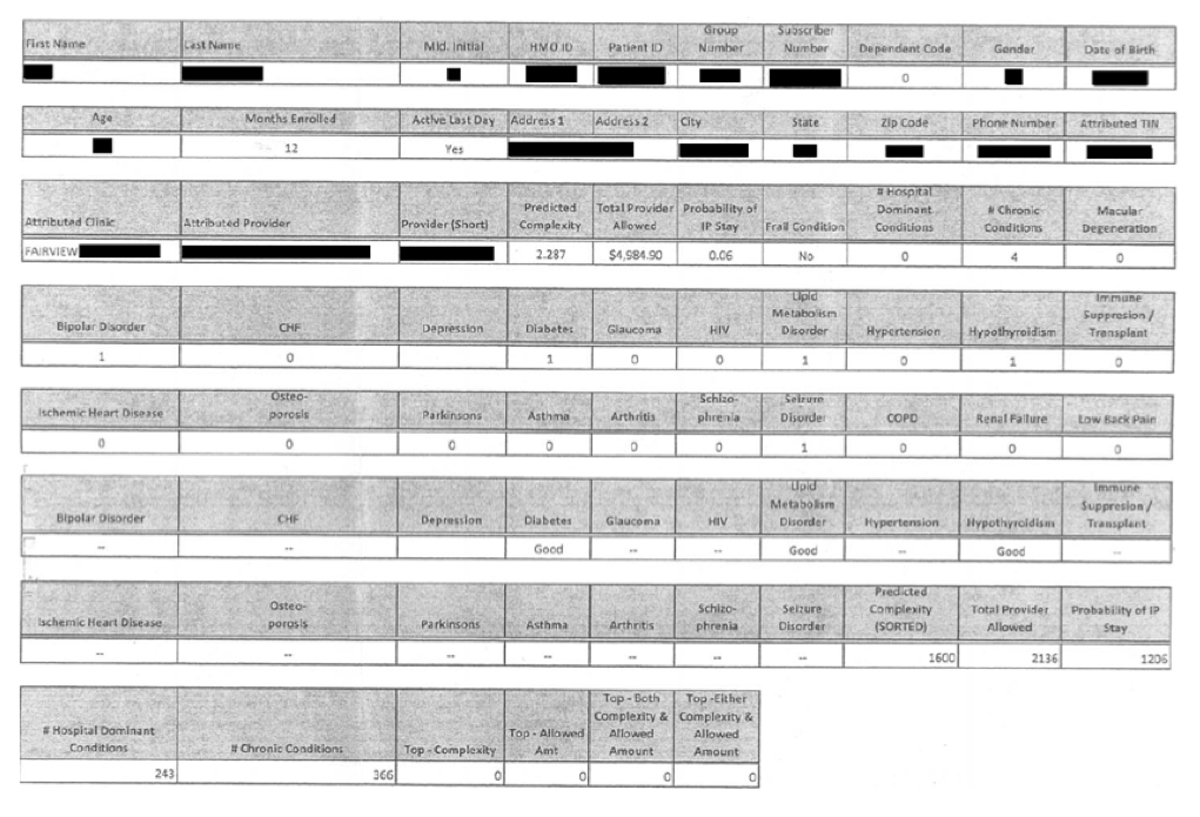

Regarding the Frailty Score, in 2011, a rather spectacular medical data breach revealed that a company called Accretive was collecting detailed and sensitive health information about hospital patients in Minnesota via contract with those hospitals, and then using that data to develop scores. A lawsuit revealed the extent of the information gathering by this company. The company was collecting the following information and developing the following scores:

· Patient’s full name

· Gender

· Number of dependents

· Date of birth

· Social Security number

· Clinic and doctor

· A numeric score to predict the “complexity” of the patient

· A numeric score to predict the probability of an inpatient hospital stay

· The dollar amount “allowed” to the provider

· Whether the patient is in “frail condition”

· Number of “chronic conditions” the patient has

· Fields to denote whether the patient has:

o Macular degeneration

o Bipolar disorder

o Depression

o Diabetes

o Glaucoma

o HIV

o Metabolism disorder

o Hypertension

o Hypothyroidism

o Immune suppression disorder

o Ischemic heart disease

o Osteoporosis

o Parkinson’s Disease

o Asthma

o Arthritis

o Schizophrenia

o Seizure disorder

o Renal failure

o Low back pain

The screenshot below is a screenshot of a patient’s data that had been revealed in the breach, redacted for the lawsuit.

One of the complaints in the lawsuit was that patients had no knowledge of this scoring activity.

“Upon information and belief, the hospitals’ patient admission and medical authorization forms do not identify Accretive by name or disclose the scope and breadth of information that is shared with it. Upon information and belief, patients are not aware that Accretive is developing analytical scores to rate the complexity of their medical condition, the likelihood they will be admitted to a hospital, their “frailty,” or the likelihood that they will be able to pay for services, among other things. [31]”

This was a complex case that illustrates the complex nature of what constitutes data broker activities. The company, Accretive, wore many hats, from debt collector to data analytics. Data analytics such as complex scoring is one form of data broker activity. However, Accretive in this case did not fit the traditional mold of data broker as list seller. No outsider can tell if the company is internally violating restrictions in existing law.

FICO’s Medication Adherence Score

FICO’s Medication Adherence Score was launched in June, 2011, According to FICO, it is using variables from the marketing world: “…those variables include age, gender, family size and asset information — such as the likelihood of car ownership — data also used by direct marketing companies. FICO says that with only a patient’s name and address, it can pull the remainder of the necessary information from publicly available sources.”[32] FICO states that the score is used to determine reminder mailings for consumers. It is unknown if the uses for the score have expanded since its introduction. Historically, prescription reminder activity has been controversial. Those chosen for reminders have not always not been very happy about it [33]. We suspect that prescription reminders are sent only to patients who have high-quality health plans and then only for high-priced, patent-protected drugs. That may be the type of information included in a score.

General Conclusions about Consumer Scoring and Data Brokers

I have mentioned above that the data business is changing and is becoming much more sophisticated. Consumer scores are a significant contributor to the change. Consumer scoring has substantial potential to become a major policy issue as scores with unknown factors and unknown uses and unknown legal constraints move into broader and broader use.

Secrecy, fairness of the factors, accuracy of the models, the inclusion of sensitive information— these are some of the key issues that must be handled. It is exquisitely unlikely that self-regulation will solve the dilemmas consumer scoring introduces. However, the path for what could constitute fair regulation in this area is already established via the history of the credit score.

Solutions

To bring fairness, accuracy, and transparency to consumers regarding data broker activities, a multi-prong approach which addresses multiple aspects of the problems needs to be pursued.

National data broker list

The Federal Trade Commission or the Consumer Finance Protection Bureau should require the industry to maintain a current list of all data brokers, with full identification, description, and contact information. If industry cannot provide the needed transparency, the agencies should create the list on their own.

National consumer data broker opt out requirement

There is an urgent need for a national consumer data broker opt-out requirement. Consumers should be able to opt out at a central portal. Data brokers should be allowed to download the list of those who have opted out. Data brokers would then be responsible for scrubbing their lists.

The opt out needs to be standardized, and could operate like Prescreen Opt Out.

Consumers would opt out at a central portal, consumer data brokers would be able to download the list of those who had opted out, then data brokers would be responsible for using this dated list to scrub their lists.

National opt out standards:

• No use of opt out data for marketing purposes

• Standardized language around opt out

• Prominent placement on home page of a button or link that says opt out

• Notice to consumers that an opt-out request has been received and acted upon

• Due process rights for consumers denied an opt out

• Consequences for data brokers that do not comply

• Opt outs for all without cost or prerequisites and with simple procedures

Reform and oversight of affiliate marketing of consumers’ personally identifiable data. Affiliate marketing of consumer information creates very significant challenges for consumers. The businesses selling the data should exercise appropriate and reasonable oversight.

List brokers who are selling PII of consumers must allow consumers to see the lists they are on and opt out. If a consumer is on a list, why can’t the consumer be made aware of that? The list could be incorrect, and could have consequences if sold to an insurer or employer.

The sale of lists that endanger lives or safety or wellness should be stopped. There are lists all of us should be able to agree should not exist. The lines can be drawn by regulatory agencies after consulting with consumers and industry

No secret consumer scores, no unfair factors. There should full publication of data elements (but not weights) used in consumer scores, and all data elements used must be reasonable.

The expansion of the FCRA to include modern eligibility options. Eligiblity uses of data have expanded. The law may need to be expanded so that proxy credit scoring or modeled credit scoring clearly fall under the law. There should also be limits on the use of sensitive information in scoring and on the sale of health data in all contexts. In addition, data brokers should be subject to strict disposal requirements and time limits for all data held. Fair Information Practices should be applied to consumer data broker practices and lists.

Better Enforcement: Civil and in some cases criminal penalties when there is a breach of the law. Private rights of action for aggrieved consumers should be allowed, togegther with effective enforcement and oversight by the FTC and CFPB.

Conclusion

I agree that the data broker industry is complex, as is our digital world, as are the lives of all of us who live in this world. But that is no excuse for avoiding the necessary discussions that will need to take place between all stakeholders.

In this testimony, I have said many things. It can be summed up in this way:

Individuals should have the right to stop harmful collection and categorization activity and to force the permanent and immediate expungement of all data that is factually incorrect, data that arrives at an incorrect conclusion about them, or data that influences decisions about a consumer in a negative way.

This was the idea behind the Fair Credit Reporting Act of 1974. It was a good idea then, and the fundamental values remain the same today.

Thank you for your attention to these matters. I welcome your questions, and will be happy to provide further research or input.

_____________________________

Endnotes

[1] For more information and to read many of the research studies and publications, see https://www.worldprivacyforum.org.

[2] Information Resellers: Consumer Privacy Framework Needs to Reflect Changes in Technology and the Marketplace, http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-13-663. Sept. 25, 2013.

[3] DEFINING MOMENTS REACTIVE BABY BOOMERS Data Card, http://datacardhub.adrearubin.com/market?page=research/datacard&id=255914. Last accessed Dec. 17, 2013.

[4] Adrea Rubin, Action Network Transaction Database, http://datacardhub.adrearubin.com/market?page=research/datacard&id=257898, last accessed Dec. 15, 2013.

[5] Warranty IT Seniors, Adrea Rubin, http://datacardhub.adrearubin.com/market?page=research/datacard&id=123434, last accessed Dec. 15, 2013.

[7] DMDatabases, Suppression, http://dmdatabases.com/data-processing/suppression, last accessed Dec. 17, 2013. Screen shot available.

[10] Adrea Rubin, Activity Tracker Low End Credit Prospects Data Card, Card ID 310015, http://datacardhub.adrearubin.com/market?page=research/datacard&id=310015 last accessed Dec. 15, 2013.

[11] Selling Consumers Not Lists: The New World of Digital Decision-Making and the Role of the Fair Credit Reporting ActEd Mierzwinski and Jeff Chester. November, 2013.

[12] Panel comments by Dr. John Deighton, National Press Club, The Value of Data: Consequences for Insight, Innovation and Efficiency in the US Economy, A Symposium Hosted by DMA’s Data-Driven Marketing Institute, October 29, 2013. Dr. Deighton was commenting on his sampling for the study,The Value of Data: Consequences for Insight, Innovation and Efficiency in the U.S. Economy, John Deighton and Peter Johnson, DDMI, 2013.

[13] http://sortedbyname.com/privacy.html, last accessed Dec. 17, 2013. Screen shot available.

[14] http://waatp.com/faq.html. Last accessed Dec 17, 2013. Screen shot available.

[15] The Direct Marketing Association’s publicly searchable Vendor Database contained 377 companies stating an expertise specifically in scoring as of Dec. 15, 2013. Some examples of companies listed include Datalogix, Analytics IQ, FICO, iKnowtion, and others.

[16] In 1995 Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae endorsed the use of credit scores as part of the mortgage underwriting process. This had a substantial impact on the use of credit scores in the mortgage loan industry. See for example Kenneth Harney, The Nation’s Housing Lenders might rely more on credit scores, The Patriot Ledger, July 21 1995.

[17] See for example, comments of Peter L. McCorkell, Senior Counsel to Wells Fargo, to the Federal Trade Commission, August 16, 2004 in response to FACT Act Scores Study.

[18] As of December 2004, the Fair Credit Reporting Act as modified by the Fair and Accurate Credit Transactions Act, or FACTA, ended score secrecy formally, and required consumer reporting agencies to provide consumers with more extensive credit score information, upon request. Also made available to the public was the context of the score (its numeric range), the date the score was created, some of the key factors that adversely affected the score, and some other items.

[19] AnalyticsIQ, http://analytics-iq.com/download/Aspects.pdf, last accessed Dec. 16, 2013.

[20] One exception to this is ID Analytics’ Identity Score, which consumers are able to see.

[21] For more information, see http://www.consumer.ftc.gov/articles/0152-how-credit-scores-affect-price-credit- and-insurance.

[22] A significant lawsuit on this issue is FTC v. Transunion which is definitive. From the press release: “The Federal Trade Commission has ordered the Trans Union Corporation to stop selling consumer reports in the form of target marketing lists to marketers who lack an authorized purpose for receiving them under the Fair Credit Reporting Act (“FCRA”). In a unanimous opinion authored by Commissioner Mozelle W. Thompson, the FTC determined that “Trans Union’s target marketing lists are . . . consumer reports under the FCRA” and concluded that Trans Union is violating the FCRA by selling this information to target marketers who lack one of the “permissible purposes” enumerated under the Act. The Commission’s decision applies to a number of Trans Union’s target marketing list products including its Master File / Selects products, its modeled products and its TransLink / reverse append products.” http://www.ftc.gov/news-events/press-releases/2000/03/trans- unions-sale-personal-credit-information-violates-fair. Full case: http://www.ftc.gov/enforcement/cases-and- proceedings/cases/2000/03/trans-union-corporation-matter.

[23] Ann McDonald, High Points for Credit Scoring: With generic scores becoming antiquated, credit-scoring providers are focusing on new offerings. Collections and Credit Risk, April 1 2006, 46 Vol. 10, No.4.

[24] LC Thomas, RW Oliver, DJ Hand, A Survey of Issues in Consumer Credit Modeling Research, The Journal of the Operational Research Society, Sept. 2005, Vol. 56, Iss. 9.

[25] Cell Phone Turndowns Mailing List, NextMark List ID #188161. http://lists.nextmark.com/market?page=order/online/datacard&id=188161, last accessed Dec. 12, 2013.

[26] http://dmdatabases.com/databases/consumer-mailing-lists/consumer-lists-by-credit-score. More information about the DMDatabases modeled credit score is at http://dmdatabases.com/databases/specialty-lists/modeled- credit-score-direct-mail-email-list.

[27] Experian ChoiceScore, http://www.experian.com/marketing-services/data-digest-choicescore.html.

[28] http://datacardhub.adrearubin.com/market?page=research/datacard&id=268601.

[29] CHOICESCORE BY EXPERIAN UNDER BANKED AND EMERGING CONSUMERS, http://datacardhub.adrearubin.com/market?page=research/datacard&id=268601.

[30] According to the data broker’s data card, two entities purchased this data: Achievecard, and Figi’s Incorporated. Figi’s Incorporated appears to be a food gift retailer. (http://www.fbsgifts.com/about.html#figis).

[31] United States District Court, District of Minnesta. State of Minnesota vs. Accetive Health, Inc.

[32] Jeremy M. Simon, New medical FICO score sparks controversy, questions, Yahoo Finance, July 28, 2011. http://finance.yahoo.com/news/New-medical-FICO-score-sparks-creditcards-1400615100.html?x=0.

[33] Weld v. CVS Pharmacy Inc., No. CIV. A. 98-0897, 1999 WL 1565175 (Mass. Super. Nov. 19, 1999), aff’d, Weld v Glaxo Wellcome, Inc., 746 N.E.2d 522 (Mass. 2001).

Download the Full Testimony