Public Comments: February 2011 WPF Responds to FTC’s Report on Privacy

Background:

The World Privacy Forum filed comments with the FTC in response to its preliminary staff report, Protecting Consumer Privacy in an Era of Rapid Change: A Proposed Framework for Businesses and Policymakers. In our comments, we urge the FTC to take affirmative steps to protect consumer privacy online and offline. Our comments include a brief history of privacy self regulation, and point out how privacy self regulation has consistently failed. The comments also discuss Do Not Track, and urge the FTC to take a broader look at tracking protections for consumers. WPF also specifically requested that the FTC identify credit reporting bureaus subject to Fair Credit Reporting Act regulations and assist consumers in locating those bureaus.

-

Download the comments (PDF)

-

or Read comments below

—–

February 18, 2011

Comments of the World Privacy Forum regarding the Federal Trade Commission Preliminary Staff Report, Protecting Consumer Privacy in an Era of Rapid Change: A Proposed Framework for Business and Policymakers.

VIA ONLINE SUBMISSION

Federal Trade CommissionOffice of the Secretary

600 Pennsylvania Avenue,

NW Washington, DC 20580

Re: A Preliminary FTC Staff Report on “Protecting Consumer Privacy in an Era of Rapid Change: A Proposed Framework for Businesses and Policymakers”

The World Privacy Forum appreciates the opportunity to submit comments on the preliminary staff report on protecting consumer privacy, http://ftc.gov/os/2010/12/101201privacyreport.pdf.

The World Privacy Forum is a nonprofit, non-partisan public interest research group. Our activities focus on research and analysis of privacy issues, along with consumer education. For more information, see https://www.worldprivacyforum.org.

We appreciate the effort and thought that clearly went into the preliminary staff report. We acknowledge that the Commission is attempting to do the right thing here.

However, as much as the World Privacy Forum welcomes the draft report and the interest shown by the Commission in consumer privacy issues, we respectfully approach the report with a sense of déjà vu. A decade ago, the Commission showed much the same interest and issued a variety of reports on consumer privacy online. It is not clear that those earlier efforts made a great difference, and it is not clear that this report will make a difference.

We reach this conclusion reluctantly, but for several different reasons.

First, despite all the activity and legislation passed, consumer privacy protections have gotten worse online. Technology is one reason. Industry has run rampant using any available technology or creating new capabilities to monitor, profile, and track consumers online. Because no one was looking, companies found new devices for tracking consumers and dismantled consumer protections that were developed. An egregious example, but not the only one, is the practice that developed of respawning cookies that users had intentionally deleted. [1] Exploiting a user’s browser history is another. [2] Only the most informed, technically proficient consumers have a hope of protecting their own privacy, and then they must devote considerable time and effort to do so.

Second, the Commission does not have any real power to stop bad industry practices. Outside of a few statutes that expressly give the Commission regulatory authority (some of which is to be transferred to the new Consumer Financial Protection Board), the Commission is largely powerless to stop bad practices generally. Many in the privacy community agree that the Commission should have broader powers, and the Commission itself has supported legislation to provide those powers. However, the legislation did not pass, and the Commission remains in much the same state that it was in ten years ago.

Enforcement actions help a bit, but they are too occasional, too often focused on marginal practices, and cannot anticipate technological or commercial developments. Too often, companies that are not the direct target of those actions pay little attention to enforcement actions, knowing that Commission resources are limited. Those companies that are the target of Commission actions know that the penalties are often weak in comparison to the profits, and that it is more cost-effective to exploit consumers today and say that they are sorry tomorrow if they are caught.

Third, industry knows that the Commission’s attention span is limited. When the Commission showed interest in online privacy in the years before 2000, industry responded by developing and loudly trumpeting a host of privacy self-regulatory activities. Most of these activities were strictly for the purpose of convincing policy makers at the Commission and elsewhere that regulation or legislation was a bad idea. All of these activities actually or effectively disappeared as soon as new appointees to the Commission demonstrated a lack of interest in regulatory or legislative approaches to privacy.

In Appendix A of these comments we have included a detailed and documented review of the most important of these failed privacy self-regulatory programs, some of which the FTC actively endorsed. We summarize that appendix here:

• The Individual Reference Services Group (IRSG) was announced in 1997 as a self-regulatory organization for companies that provide information that identifies or locates individuals. The group terminated in 2001, deceptively citing a newly passed regulatory law that made self regulation unnecessary. However, that law did not cover IRSG companies.

• The Privacy Leadership Initiative began in 2000 to promote self regulation and to support privacy educational activities for business and for consumers. The organization lasted about two years.

• The Online Privacy Alliance began in 1998 with an interest in promoting industry self regulation for privacy. OPA’s last reported activity appears to have taken place in 2001, although its website continues to exist and shows signs of an update in 2011.

• The Network Advertising Initiative had its origins in 1999, when the Federal Trade Commission showed interest in the privacy effects of online behavioral targeting. By 2003, when FTC interest in privacy regulation had evaporated, the NAI had only two members. Enforcement and audit activity lapsed as well. NAI did nothing to fulfill its promises or keep its standards up to date with current technology until 2008, when FTC interest increased.

• The BBBOnline Privacy Program began in 1998, with a substantive operation that included verification, monitoring and review, consumer dispute resolution, a compliance seal, enforcement mechanisms and an educational component. Several hundred companies participated in the early years, but interest did not continue and BBBOnline stopped accepting applications in 2007.

The clear historical lesson is that privacy self regulation by industry (never very robust to begin with) will fail again once the pressure is off. The FTC report suggests that a Do-Not-Track mechanism “could be accomplished by legislation or potentially through robust, enforceable self regulation.” [3] We believe continued FTC support of self regulation in the area of privacy is not appropriate. We now have repetitive, specific, tangible examples of failed self regulation in the area of privacy. These examples are not mere anecdotes – these were significant national efforts that regulators took seriously.

In the online space, we now have over a decade of failure with the NAI. Self regulation in the online advertising area has failed and is not a feasible or even logical option anymore. In the preliminary report, the FTC asked about an icon program for consumer notice on mobile devices. It is tempting to delve into the details and explain each nuance of why notice via an icon on a mobile device does not protect consumer privacy. We understand that self regulation can take many flavors. An icon is just the latest variety. The general principle here suffices: if the FTC chooses to implement privacy protections for consumers via self regulation, we believe based on historic precedent that history will repeat itself resulting in no meaningful consumer protection.

Unfortunately, there is one difference this time; that is, we are at a crucial juncture in the timeline of Internet development. If self regulation is allowed to be the primary consumer privacy protection mechanism, then we believe consumers will not have adequate or appropriate protections in the online or digital media spheres going forward as a precedent. Ultimately, we find the FTC support of self regulation as an option to be unrealistic and ungrounded in actual historic facts.

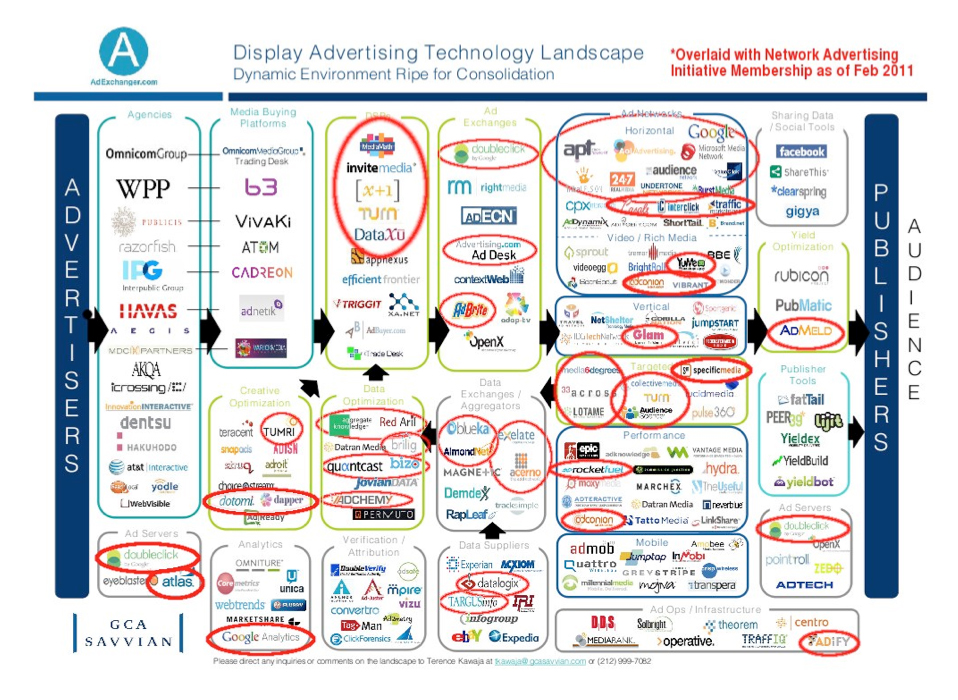

We reluctantly note that some other recommendations in the staff report are similarly lacking in factual grounding. The report continues to also emphasize notice and choice as a viable mechanism for protecting consumers. Notice and choice is a mantra that industry has promoted actively for years because it is ineffective. Calling for “informed and meaningful choices”[4] only places subtle changes on this phrase. The past two decades have demonstrated that consumers cannot protect their privacy online by exercising choice. The web has grown far too complex for that, and business models based on exploiting consumer data have grown far too elaborate for consumers to understand. Figure 1, below, provides an overview of how current self regulation is tackling consumer privacy. Current NAI members are circled in red. Note that an entire industry has grown up and developed around the NAI, which represents approximately 1/3 of the ecosystem.

Figure 1. NAI Members in the Online Advertising Ecosystem

This graphic of the online advertising ecosystem with NAI members circled in red is merely illustrative of the online advertising industry. It is not comprehensive with regard to members of the industry or the NAI, but nevertheless shows that entire categories of actors in the advertising business, and big players such as data brokers, remain entirely outside the NAI. (The original graphic, which did not have NAI members highlighted, was produced by the investment-banking firm GCA Savvion. The highlighted graphic was produced by Samuelson Law, Technology, & Public Policy Clinic at UC Berkeley Law)

Almost everyone in the privacy world – including many in the business community – now recognizes the sheer impracticalities of notice and choice. Yet the same failed idea is still being promoted as a viable option by the Commission’s staff. Today it is an icon, tomorrow it will be something else. This time will not be different, no matter how the notice is framed or delivered, and no matter how meaningful the choice.

The support in the staff report for a Do-Not-Track (DNT) mechanism is noted and appreciated. DNT is a complex idea, with many facets and different implementations. The staff report did not look at DNT in sufficient detail, nor was the recommendation specific enough to further the ongoing discussions. The final report should do better, and needs to lay out a vision of just how DNT should work.

While DNT may have a place in protecting consumers on the Internet, we wish that the Commission’s staff had taken a broader look at the tracking of consumers in the modern world. Tracking consumers online is just a part of the puzzle. Consumers are being tracked on their cell phones, in their cars, on the street, and by digital signage in stores and malls.

Just over a year ago, the World Privacy Forum issued a report entitled The One-Way-Mirror Society: Privacy Implications of the New Digital Signage Networks early in 2010. The report’s basic finding was:

New forms of sophisticated digital signage networks are being deployed widely by retailers and others in both public and private spaces. From simple people- counting sensors mounted on doorways to sophisticated facial recognition cameras mounted in flat video screens and end-cap displays, digital signage technologies are gathering increasing amounts of detailed information about consumers, their behaviors, and their characteristics. [5]

In Appendix B, we have included a summary of the findings of this report.

The idea of DNT in its inception in 2007 was to create a broad mechanism that opted consumers simply out of tracking by multiple entities. The core of the idea was to create simplicity of opt out in a sea of ecosystem complexity. Currently, the DNT discussion has largely focused on granular definitions of how DNT would look for a web browser. DNT has also pivoted on HTTP browser headers. While we support these discussions and find them helpful, we also note that they are not the comprehensive vision that an effective or ultimately meaningful DNT must include.

We repeat: Do Not Track is about much more than web browsing, and it must be in order to be truly effective in today’s world, and especially in tomorrow’s.

We believe that the Commission staff must take a broader look at the problem of the tracking of consumers and the privacy implications of that tracking. Little will be accomplished by a highly narrow and technical DNT mechanism if all other consumer tracking technologies are left to develop without any policy guidance and without any substantive, enforceable limits. Consumers will not welcome DNT if every move they make in a store, mall, or other public space is recorded, compiled, and used to direct their opportunities in the market for products, services, credit, housing, employment, insurance, and otherwise. The Commission needs to focus on the broader picture here and to try to get ahead of developments before they become so embedded in business practices that any limit will be fought as the end of the world as we know it, a cry heard too often on the Internet.

The Commission could provide information valuable to the national debate over DNT by collecting and reporting on the relative importance of advertising and behavioral targeting to advertising-supported websites. Industry-sponsored studies that claim that any restriction on behavioral advertising would result in An End To The Internet As We Know It are biased and inherently unbelievable. However, no independent public-interest study conducted by someone without direct industry support can obtain access to the necessary information.

One analyst argues with some force that DNT would not significantly threaten advertising supported Internet businesses. He suggests that “projections place behavioral advertising at only 7% of the U.S. online advertising market in 2014.” [6] If true, then it places an entirely different light on the debate. The Commission can obtain information that others cannot, and it has economists who can evaluate the data. That type of study would be beneficial to the ongoing discussions and would provide Congress with facts that would be directly relevant to legislation now under consideration. This should be a high priority.

An adjunct to this broader DNT issue is something we talked about at the FTC roundtables: ease of opt outs for consumers. There are 10,000 business models blossoming today. We believe consumers should not have to traipse around and find 10,000 opt outs. We are still requesting some very specific items from the FTC:

- That the FTC compile a list of all FCRA-covered credit bureaus, including the specialty credit bureaus. Currently, consumers do not have a way of finding the smaller credit reporting entities, and as such cannot meaningfully exercise their rights under the FCRA.

- That the FTC compile a list of data brokers with links to opt outs that are available to consumers. The Privacy Rights Clearinghouse and the World Privacy Forum both provide opt-out pages for consumers, but our lists are of necessity incomplete simply because we do not have the resources to find each and every data broker.

- And we still like the idea of the FTC managing a broad DNT clearinghouse or center or mechanism. DNT as a narrow browser issue is fine, but it does not come close to the original impetus behind the idea: easy, centralized opt-outs of tracking for consumers who face a highly complex business landscape. This landscape can include FCRA- regulated entities, web sites, and digital signage in public spaces, among many other kinds of tracking. There needs to be a central place consumers know to go, and this central place we believe should be the FTC.

We did find many things in the report that we liked. The emphasis on the life cycle of products, services, and personal information is welcome. There appears to be some recognition in the report that the Commission’s previous approach to Fair Information Practices – an approach that left out important principles and watered down some others – was a mistake. The staff report should expressly state its support for the full set of FIPs as defined by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development in 1980. Even the Commerce Department’s recent report, which generally showed insufficient interest in protecting consumers, supported classic FIPs. [7]

The WPF appreciates the effort that went into the staff report and the concern for consumer privacy reflected throughout the draft. Fresh ideas, frank recognition of the problems consumers face, and effective new approaches are needed. We reiterate the urgent need for the FTC to move away from self regulation. We reiterate the urgent need for a broader vision and implementation of a Do Not Track mechanism or clearinghouse for consumers. We know the FTC cares about privacy, and has put a great deal of thought into how to approach privacy in a modern world. Now it is time to create broad, enforceable mechanisms that will assist consumers as they attempt to navigate an increasingly complex world.

Thank you for your efforts. Please do not hesitate to contact us with any questions we may assist the Commission with.

Respectfully submitted,

s/

Pam Dixon

Executive Director,

World Privacy Forum

Appendix A

A History of Industry Self-Regulatory Actions on Privacy

1. Individual Reference Services Group

The creation of the Individual Reference Services Group (IRSG) was announced in June 1997 at a workshop held by the Federal Trade Commission. [8] According to a document filed with the FTC, the group consisted of companies that offer “individual reference services” or provide information that identifies or locates individuals. [9] The IRSG reported fourteen “leading information industry companies” as members, including US Search.com, Acxiom, Equifax, Experian, Trans Union, and Lexis-Nexis. [10]

The IRSG described its self-regulatory activities:

The core of the IRSG’s self-regulatory effort is the self-imposed restriction on use and dissemination of non-public information about individuals in their personal (not business) capacity. In addition, IRSG members who supply non-public information to other individual reference sewices will provide such information only to companies that adopt or comply with the principles. The principles define the measures that IRSG members will take to protect against the misuse of this type of information, The restrictions on the use of non-public information are based on three possible types of distribution that the services provide. [11]

The industry self-regulatory plan appears to accomplish the purpose of avoiding regulation. In its 1999 report to Congress, the FTC recommended that industry be left to regulate itself.

A. Recommendations Regarding the IRSG Principles

The Commission recommends that the IRSG Group be given the opportunity to demonstrate the viability of the IRSG Principles.

The present challenge is to protect consumers from threats to their psychological, financial, and physical well-being while preserving the free flow of truthful information and other important benefits of individual reference services. The Commission commends the initiative and concern on the part of the industry members who drafted and agreed to the IRSG Principles, an innovative and far- reaching self-regulatory program. The Principles address most concerns associated with the increased availability of non-public information through individual reference services. With the promising compliance assurance program, the Principles should substantially lessen the risk that information made available through the services is misused, and should address consumers’ concerns about the privacy of non-public information in the services’ databases. Therefore, the Commission recommends that the IRSG Group be given the opportunity to demonstrate the viability of the IRSG Principles. ***

The Commission looks to industry members to determine whether errors in the transmission, transcription, or compilation of public records and other publicly available information are sufficiently infrequent as to warrant no further controls. While the Commission believes the IRSG Principles address most areas of concern, certain issues remain unresolved.(303) Most notably, the Principles fail to provide individuals with a means to access the public records and other publicly available information that individual reference services maintain about them. Thus, individuals cannot determine whether their records reflect inaccuracies caused during the transmission, transcription, or compilation of such information. The Commission believes that this shortcoming may be significant, yet recognizes that the precise extent of these types of inaccuracies and associated harm has not been established. An objective analysis could help resolve this issue. The IRSG Group has acknowledged the Commission’s position, and has demonstrated its awareness of this problem by (1) stating that it will seriously consider conducting a study of this issue and (2) agreeing to revisit the issue in eighteen months. The Commission looks to industry members to undertake the necessary measures to establish whether inaccuracies and associated harm resulting from errors in the transmission, transcription, or compilation of public records and other publicly available information are sufficiently infrequent as to warrant no further controls. [12]

One of the IRSG principles called for an annual “assurance review” for compliance with IRSG standards. [13] IRSG also required that a summary of the report and any subsequent actions taken or response be made publicly available. While the IRSG website contains some evidence that the reviews were conducted, it did not make the reports public on its website. [14]

Once the threat of regulation evaporated or diminished, the IRSG continued in existence for a few years. In September 2001, approximately four years after it was established, the IRSG announced its termination. [15] The stated reason was that legislation made the self-regulatory principles no longer necessary.

“We are operating in a much different regulatory environment than we were when the IRSG was created in 1997,” said Ron Plesser with Piper Marbury Rudnick & Wolfe LLP, whose firm represents the IRSG. “It doesn’t make sense to maintain a self-regulatory program when this information is now regulated under the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act.” [16]

However, the regulatory legislation cited as the reason for termination did not regulate IRSG members. The Gramm-Leach-Bliley (GLB) Act provided that each “financial institution” has an “affirmative and continuing obligation to respect the privacy of its customers and to protect the security and confidentiality of those customers’ nonpublic personal information.” [17] A financial institution is a company that offers financial products or services to individuals, like loans, financial or investment advice, or insurance. [18] The IRSG companies – companies provide information that identifies or locates individuals – are not financial institutions under GLB.

Why did the IRSG issue a deceptive statement about the reason for its termination? According to reports current at the time, the members of IRSG lost interest in supporting a self-regulatory organization because they no longer felt threatened by legislation or regulatory activities. It is also noteworthy that GLB became law almost two years before it was cited as the reason for the end of the IRSG.

2. Privacy Leadership Initiative

A group of industry executives with members including IBM, Procter & Gamble, Ford, Compaq, and AT&T established the Privacy Leadership Initiative (PLI) in June 2000. [19] PLI began an ad campaign in national publications to promote industry self regulation of online consumer privacy. The initiative follows a recent Federal Trade Commission recommendation that Congress establish legislation to protect online consumer privacy.” [20]

A description of the PLI from its website in 2001 stated:

The Privacy Leadership Initiative was formed by leaders of a number of different companies and associations who believe that individuals should have a say in how and when their personal information can be used to their benefit.

The purpose of the PLI is to create a climate of trust which will accelerate acceptance of the Internet and the emerging Information Economy, both online and off-line, as a safe and secure marketplace. There, individuals can see the value they receive in return for sharing personally identifiable information and will understand the steps they can take to protect themselves. As a result of sharing, individuals will have the power to enhance the quality of their lives through personalized information, products and services. [21]

Another statement from the PLI website provides a more expansive statement of the origin and purpose of the organization:

Why We Formed

The PLI was formed to provide consumers with increased knowledge and resources to help them make informed choices about sharing their personal information. We also help businesses, both large and small — in all industries — develop and maintain good privacy practices. Trust and choice are the foundation of good privacy practices, yet research shows that there is currently a lack of trust between consumers and businesses. Individuals must trust responsible businesses to use personal information in ways that benefit them — such as better, less expensive and personalized products and services — while also providing them with choices about how much personal information is gathered and by whom. Through the establishment of a common understanding about the benefits of exchanging personal information and how it can be safeguarded, the PLI will begin to restore consumer confidence.

What We’re Doing

Given that privacy is a question of trust and behavior, the PLI is developing an “etiquette”–model practices for the exchange of personal information between businesses and consumers. We will help create this code of conduct by engaging in a multi-year, multi-level effort to educate consumers and businesses. Specifically, the PLI will:

1. Conduct original research to measure and track attitudes and behavior changes among consumers and to better understand how the flow of information affects the economy and people’s lives on a day-to-day basis;

2. Compile and refine existing privacy guidelines and create The Privacy Manager’s Resource Center, a new service for that assists businesses in developing their privacy programs

3. Design an interactive Web site — understandingprivacy.org — to make privacy simpler for consumers, businesses, trade groups, journalists, academics, policymakers and all other interested parties; and

4. Educate consumers about technology and tools that protect their interests without diminishing the benefits of exchanging personal preferences with responsible companies.

Whether online or off, the flow of information is critical to the growth and success of our economy. Members of the PLI recognize that businesses must take an active role in ensuring that privacy practices evolve to meet consumer needs. While there is no simple answer for an issue this complex, for PLI members that means understanding what individuals want, tackling those challenges and initiating change, while being accountable and building confidence. These are the keys to creating a climate of trust between responsible businesses and consumers. [22]

Other accounts from support the notion that PLI was intended to promote self regulation. A 2001 story on Internet privacy from a publication of the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania stated:

While Congress debates legislation on Capitol Hill, the business community is actively promoting other options. Chief among these is self regulation.

Earlier this month, for example, the Privacy Leadership Initiative (PLI) – a group of executives from such companies as AT&T, Dell Computer, Ford, IBM and Procter & Gamble – announced a $30-$40 million campaign aimed at showing consumers how they can use technology to better protect their privacy online. [23]

By the middle of 2002, the threat of regulation has diminished enough so that PLI “transitioned” its activities to others. The BBBOnLine, a program of the Better Business Bureau system, [24] took over the PLI website (understandingprivacy.org). The BBBOnline privacy program, which lasted longer than PLI, is no longer operational, and the details are discussed elsewhere in this paper.

By the middle of September, 2002, the transition of the website to BBBOnLine appeared to be complete. [25] However, by January 2008, the understandingprivacy.org website had changed entirely, offering visitors an answer to the question Can microwave popcorn cause lung disease? [26] By the beginning of 2011, the understandingprivacy.org website was controlled by Media Insights, a creator of “content-rich Internet publications.” [27] Other Media Insights websites include BunnyRabbits.org, Feathers.org and PetBirdReport.com. [28]

3. Online Privacy Alliance

The Online Privacy Alliance [29] was created in 1998 by former Federal Trade Commissioner Christine Varney. [30] OPA’s earliest available webpage described the organization as a cross- industry coalition of more than 60 global corporations and associations. [31]

The first paragraph of the background page on its website stated clearly its interest in promoting self regulation:

Businesses, consumers, reporters and policy makers at home and abroad are watching closely to see how well the private sector fulfills its commitment to create a credible system of self regulation that protects privacy online. One of the most important signs that self regulation works is the growing number of web sites posting privacy policies. [32]

In July 1998, OPA released a paper describing Effective Enforcement of Self Regulation. [33] In November 1999, a representative of the OPA appeared at an FTC workshop on online profiling and participated in a session on the role of self regulation. [34] OPA self-regulatory principles were cited by industry representatives before the FTC and elsewhere. [35]

It is difficult to chart with precision the deterioration of the OPA. Wikipedia categorizes OPA under defunct privacy organizations. [36] A review of webpages available at the Internet Archive shows a decline of original OPA activities starting in the early 2000s. For example, the first webpage available for 2004 prominently lists OPA news, but the first item shown is dated March 2002 and the next most recent item is dated November 2001. [37] The OPA news on the first webpage available for 2005 shows four press stories from 2004, but the most recent OPA item was still November 2001. [38] By 2008, The OPA news on the first webpage available for that year shows 2 news stories from 2006, and no reported OPA activity more recent than 2001. [39] There is little or no evidence after 2001 of OPA activities or participation at the Federal Trade Commission. [40] The threat that fostered the creation of the OPA apparently had disappeared.

The OPA website continues to exist and appears to have been reformatted and updated at some time after 2008. The website has a link to a February 4, 2011, blog entry from another website titled Six Ways Your Online Privacy Is at Risk. [41] Several other links to 2011 items also appear, but clicking on the more opa news link at the bottom links to a webpage that shows no item more recent than 2001. [42] The main OPA webpage also includes links to old OPA documents such as Guidelines for Online Privacy Policies (approximately 533 words) and Guidelines for Effective Enforcement of Self-Regulation (approximately 1269 words). The website continues to offer a white paper titled Online Consumer Data Privacy in the United States and dated November 19, 1998.

The list of members still on its website includes at least one company that no longer exists and a trade association that changed its name. [43] The membership page is not dated, and members number approximately 30, or less than half the number reported in 1998.

4. Network Advertising Initiative (1999-2007, updated 2008-2011)

Note: This summary is adapted from a comprehensive review of the Network Advertising Initiative (NAI) prepared by the World Privacy Forum in 2007. The WPF report is THE NETWORK ADVERTISING INITIATIVE: Failing at Consumer Protection and at Self regulation. [44] The WPF report contains citations and support for the conclusions presented here.

The network advertising industry announced the formation of the Network Advertising Initiative at an FTC workshop in 1999. The NAI standards, a 21 page document, were issued the next year. [45] The core concept – the opt-out cookie – has been criticized as a technical and policy failure. [46]

When it began, NAI membership consisted of 12 companies, a fraction of the industry engaging in behavioral ad targeting. By 2002, membership hit a low of two companies. [47] When NAI created a category of associate members who were not required to be in full compliance with the NAI standards, membership increased, with associate members outnumbering regular members by 2006. Eventually, the associate membership category was eliminated. [48]

Enforcement of the NAI standards was delegated to TRUSTe, an unusual action given that TRUSTe was a member of NAI for one year. [49] Over several years, the scope of TRUSTe public reporting on NAI complaints decreased consistently until 2006 when separate reporting about NAI by TRUSTe stopped altogether. [50] There is no evidence that audits of NAI members – required by NAI principles – were conducted. No information about audits of members was ever made public. [51]

Much of the pressure that produced the NAI came from the Federal Trade Commission. Industry reacted in 1999 to an FTC behavioral advertising workshop, and the NAI self-regulatory principles were drafted with the support of the FTC. [52] Pressure from the FTC diminished or disappeared quickly, and by 2002, only two NAI members remained. When the FTC again showed interest in online behavioral advertising in 2008, the NAI began to take steps to fix the problems that had developed with its 2000 principles. [53] One of those steps was “promoting more robust self regulation by today opening a 45-day public comment period concurrent with the release of a new draft 2008 NAI Principles.” [54] NAI never sought public comment on the original principles. It is too soon to evaluate the new NAI efforts.

There were other, more substantive problems with the NAI principles. The conclusion of the World Privacy Forum Report summarizes the NAI failures:

The NAI has failed. The agreement is foundationally flawed in its approach to what online means and in its choice of the opt-out cookie as a core feature. The NAI opt-out does not work consistently and fails to work at all far too often. Further, the opt-out is counter-intuitive, difficult to accomplish, easily deleted by consumers, and easily circumvented. The NAI opt-out was never a great idea, and time has shown both that consumers have not embraced it and that companies can easily evade its purpose. The original NAI agreement has increasingly limited applicability to today’s tracking and identification techniques. Secret cache cookies, Flash cookies, cookie re-setting techniques, hidden UserData files, Silverlight cookies and other technologies and techniques can be used to circumvent the narrow confines of the NAI agreement. Some of these techniques, Flash cookies in particular, are in widespread use already. These persistent identifiers are not transparent to consumers. The very point of the NAI self regulation was to make the invisible visible to consumers so there would be a fair balance between consumer interests and industry interests. NAI has not maintained transparency as promised.

The behavioral targeting industry did not embrace its own self regulation. At no time does it appear that a majority of behavioral targeters belong to NAI. For two years, the NAI had only two members. In 2007 with the scheduling of the FTC’s new Town Hall meeting on the subject, several companies joined NAI or announced an intention to join. Basically, the industry appears interested in supporting or giving the appearance of supporting self regulation only when alternatives are under consideration. Enforcement of the NAI has been similarly troubled. The organization tasked with enforcing the NAI was allowed to become a member of the NAI for one year. This decision reveals poor judgment on the part of the NAI and on the part of TRUSTe, the NAI enforcement organization. Further, the reporting of enforcement has been increasingly opaque as TRUSTe takes systematic steps away from transparent reporting on the NAI. If the enforcement of the NAI is neither independent nor transparent, then how can anyone determine if the NAI is an effective self-regulatory scheme? The result of all of these and other deficiencies is that the protections promised to consumers have not been realized. The NAI self-regulatory agreement has failed to meet the goals it has stated, and it has failed to meet the expectations and goals the FTC laid out for it. The NAI has failed to deliver on its promises to consumers.[55]

We note that the 2008 update of the NAI program further weakened the program. For example, the definition of sensitive medical information became narrow to the point of being nonsensical, and the NAI no longer required a central opt-out cookie. (It became voluntary to post a cookie on the central NAI opt-out page.) Enforcement and transparency did not appear to improve in the 2008 update.

As of 2011, the NAI’s central opt-out website lists 66 “fully compliant members” participating in their opt-out program. [56] However, the online privacy research group PrivacyChoice.org has compiled a list over 275 companies currently tracking consumers for the purposes of behavioral advertising. [57] This means that over 200 companies are not part of the leading self-regulatory effort; thus the NAI appears to cover less than 1/3 of the industry landscape. These other companies are not apparently part of any centralized opt-in mechanism, meaning that consumers have to spend significant amounts of time learning of their existence, investigating their privacy policies, and attempting to effectuate their opt out mechanism (if any is offered).

5. BBBOnline Privacy Program

The BBBOnline Privacy Program began in 1998, in response to “the need identified by the Clinton Administration and businesses for a major self-regulation initiative to protect consumer privacy on the Net and to respond to the European privacy initiatives.” [58] Founding sponsors including leading businesses, including AT&T, GTE, Hewlett-Packard, IBM, Procter & Gamble, Sony Electronics, Visa, and Xerox. [59] The program was operated by the Council of Better Business Bureaus (CBBB) through its subsidiary, BBBOnLine.

The BBBOnline Privacy Program was much more extensive than many other efforts at the time. It included “verification, monitoring and review, consumer dispute resolution, a compliance seal, enforcement mechanisms and an educational component.” [60] To qualify, a company had to post a privacy notice telling consumers what personal information is being collected, how it will be used, choices they have in terms of use. Participants also had to verify security measures taken to protect their information, abide by their posted privacy policies, and agree to a independent verification by BBBOnLine. Companies also had to participate in the programs’ dispute resolution service, [61] a service that operated under a 17-page set of detailed procedures. [62] The dispute resolution service also reported publicly statistics about its operations. [63] As noted above, the BBBOnLine Privacy Program took over the Privacy Leadership Initiative website (understandingprivacy.org) when PLI ended operations in 2002.

It is difficult to determine how many companies participated in the BBBOnline privacy program. A 2000 Federal Trade Commission report on online privacy said that “[o]ver 450 sites representing 244 companies have been licensed to post the BBBOnLine Privacy Seal since the program was launched” in March 1999. [64] Whether the numbers increased in subsequent years is unknown, but the 2000 number clearly represent a tiny fraction of websites and companies. It may be that the more rigorous requirements that BBBOnline asked its members to meet was a factor in dissuading some companies from participating.

BBBOnline stopped accepting applications for its privacy program sometime in 2007. [65] The specific reasons the program terminated are not clear, but it seems likely that it was the result of lack of support, participation, and interest. Self regulation for the purpose of avoiding real regulation is one thing, but the active and substantial self regulation offered by BBBOnline may have been too much for many potential participants. BBBOnline continues to operate other programs, including an EU Safe Harbor dispute resolution service, [66] but there is no evidence on its website of the BBBOnline privacy program. Interestingly, some companies continue to cite the now-defunct BBBOnline privacy program in their privacy policies. [67]

Appendix B

From The One-Way-Mirror Society: Privacy Implications of the New Digital Signage Networks, a 2010 Report by the World Privacy Forum, available at https://www.worldprivacyforum.org/pdf/onewaymirrorsocietyfs.pdf.

Brief Summary of Report

New forms of sophisticated digital signage networks are being deployed widely by retailers and others in both public and private spaces. From simple people-counting sensors mounted on doorways to sophisticated facial recognition cameras mounted in flat video screens and end-cap displays, digital signage technologies are gathering increasing amounts of detailed information about consumers, their behaviors, and their characteristics.

These technologies are quickly becoming ubiquitous in the offline world, and there is little if any disclosure to consumers that information about behavioral and personal characteristics is being collected and analyzed to create highly targeted advertisements, among other things. In the most sophisticated digital sign networks, for example, individuals watching a video screen will be shown different information based on their age bracket, gender, or ethnicity.

While most consumers understand a need for security cameras, few expect that the video screen they are watching, the kiosk they are typing on, or the game billboard they are interacting with is watching them while gathering copious images and behavioral and demographic information. This is creating a one-way-mirror society with no notice or opportunity for consumers to consent to being monitored in retail, public, and other spaces or to consent to having their behavior analyzed for marketing and profit.

The privacy problems inherent in these networks are profound, and to date these issues have not been adequately addressed by anyone. Digital signage networks, if left unaddressed, will very likely comprise a new form of sophisticated marketing surveillance leading to abuses of the collected information.

Summary of Recommendations

Principal preliminary recommendations discussed in the report include:

• Better notice and disclosure to consumers

• No one-sided industry self regulation

• No price or other unfair discrimination

• The full set of Fair Information Practices must apply for compiled information • Notice given to consumers about subpoenas for their information

• Prohibitions on digital signage in bathrooms, health facilities, etc.

• More robust consumer choices regarding data capture and use from signage

• Special rules for collection and use of pictures and information about children

#####

_____________________________

Endnotes

[1] See, e.g., Ashkan Soltani et al., Flash Cookies and Privacy (2009), http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1446862 (last visited 2/15/11).

[2] See,e.g., Cory Doctorow, Who Spies on your Browser History? (2010), http://boingboing.net/2010/12/01/who- spies-on-your-br.html (last visited 2/15/11).

[3] FTC Preliminary Staff Report at 66.

[4] Id. at 57.

[5] World Privacy Forum, The One-Way-Mirror Society: Privacy Implications of the New Digital Signage Network (2010), https://www.worldprivacyforum.org/pdf/onewaymirrorsocietyfs.pdf, last visited 2/15/11).

[6] Jonathan Mayer, Do Not Track Is No Threat to Ad-Supported Businesses, http://cyberlaw.stanford.edu/node/6592 (last visited 2/15/11).

[7] Department of Commerce Internet Policy Task Force, Commercial Data Privacy and Innovation in the Internet Economy: A Dynamic Policy Framework (2010), http://www.commerce.gov/sites/default/files/documents/2010/december/iptf-privacy-green-paper.pdf (last visited 2/15/11).

[8] Federal Trade Commission, Individual Reference Services, A Report to Congress (1997), http://www.ftc.gov/bcp/privacy/wkshp97/irsdoc1.htm (last visited 2/8/11).

[9] Individual Reference Services Group, Industry Principles — Commentary (Dec. 15, 1997), http://www.ftc.gov/os/1997/12/irsappe.pdf (last visited 2/8/11).

[10] http://web.archive.org/web/19990125100333/http://www.irsg.org (last visited 2/8/11).

[11] Id.

[12] Federal Trade Commission, Individual Reference Services, A Report to Congress (1997) (Commission Recommendations), http://www.ftc.gov/bcp/privacy/wkshp97/irsdoc1.htm (last visited 2/8/11).

[13] http://web.archive.org/web/20020210151622/www.irsg.org/html/3rd_party_assessments.htm (last visited 2/8/11).

[14] See http://web.archive.org/web/20020215163015/www.irsg.org/html/irsg_assessment_letters–2000.htm (last visited 2/8/11). Whether the reports were made public in other ways has not been explored.

[15] http://web.archive.org/web/20020202103820/www.irsg.org/html/termination.htm (last visited 2/8/11).

[16] Id.

[17] 15 U.S.C. § 6801(a).

[18] 15 U.S.C. § 6809(3). See also Federal Trade Commission, In Brief: The Financial Privacy Requirements of the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act (2002), http://business.ftc.gov/documents/bus53-brief-financial-privacy-requirements- gramm-leach-bliley-act (last visited 2/8/11).

[19] See Marcia Savage, New Industry Alliance Addresses Online Privacy, Computer Reseller News (06/19/00), http://technews.acm.org/articles/2000-2/0621w.html#item13 (last visited 2/7/11).

[20] Id (emphasis added).

[21] http://web.archive.org/web/20010411210453/www.understandingprivacy.org/content/about/index.cfm (last visited 2/7/11).

[22] http://web.archive.org/web/20010419185921/www.understandingprivacy.org/content/about/fact.cfm (last visited 2/7/11).

[23] Up for Sale: How Best to Protect Privacy on the Internet, Knowledge@Wharton (March 19, 2001), http://knowledge.wharton.upenn.edu/article.cfm?articleid=325 (last visited 2/7/11).

[24] Press Release, Privacy Leadership Initiative Transfers Initiatives to Established Business Groups (July 1, 2002), http://goliath.ecnext.com/coms2/gi_0199-1872940/Privacy-Leadership-Initiative-Transfers-Initiatives.html (last visited 2/7/11).

[25] http://web.archive.org/web/20020914095335/www.bbbonline.org/understandingprivacy (last visited 2/7/11).

[26] http://web.archive.org/web/20080118171946/http://www.understandingprivacy.org (last visited 2/7/11).

[27] http://www.mediainsights.com (last visited 2/7/11).

[28] Id.

[29] The main webpages for the organization are at www.privacyalliance.org. However, for a brief period starting in 2005, the Internet Archive shows that the organization also maintained webpages at www.privacyalliance.com. The first pages reported by the Internet Archive for www.privacyalliance.org is dated December 2, 1998.

[30] http://web.archive.org/web/19990209062744/www.privacyalliance.org/join/background.shtml (last visited 2/8/11).

[31] http://web.archive.org/web/19990209062744/www.privacyalliance.org/join/background.shtml (last visited 2/8/11).

[32] http://web.archive.org/web/19990209062744/www.privacyalliance.org/join/background.shtml (last visited 2/8/11).

[33] http://web.archive.org/web/19981202200600/http://www.privacyalliance.org (last visited 2/8/11).

[34] http://www.ftc.gov/bcp/workshops/profiling/991108agenda.htm (last visited 2/8/11).

[35] See, e.g., Statement of Mark Uncapher, Vice President and Counsel, Information Technology Association of America, before the Federal Trade Commission Public Workshop on Online Profiling (October 18, 1999), http://www.ftc.gov/bcp/workshops/profiling/comments/uncapher.htm (last visited 2/8/11).

[36] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Online_Privacy_Alliance (last visited 2/8/11).

[37] http://web.archive.org/web/20040122052508/http://www.privacyalliance.org (last visited 2/8/11).

[38] http://web.archive.org/web/20050104085718/http://www.privacyalliance.org (last visited 2/8/11).

[39] http://web.archive.org/web/20080201111641/http://www.privacyalliance.org (last visited 2/8/11).

[40] www.ftc.gov (last visited 2/8/11)

[41] http://www.privacyalliance.org (the first link under OPA News is to http://www.fastcompany.com/1723915/six- ways-your-online-privacy-is-at-risk?partner=rss), (last visited 2/8/11).

[42] http://www.privacyalliance.org/news (last visited 2/8/11).

[43] http://www.privacyalliance.org/members (last visited 2/8/11).

[44] https://www.worldprivacyforum.org/pdf/WPF_NAI_report_Nov2_2007fs.pdf (last visited 2/8/11). 45 Id. at 7-8.

[46] Id. at 14-16.

[47] Id at 28-29.

[48] Id. at 29-30.

[49] Id. at 25.

[50] Id. at 33-36.

[51] Id. at 37.

[52] Id. at 9.

[53] See, e.g., Network Advertising Initiative, Written Comments in Response to the Federal Trade Commission Staff’s Proposed Behavioral Advertising Principles (April 2008), http://www.ftc.gov/os/comments/behavioraladprinciples/080410nai.pdf (last visited 2/8/11).

[54] Id.

[55] World Privacy Forum NAI Report at 39.

[56] The NAI’s opt-out website is located at: http://www.networkadvertising.org/managing/opt_out.asp

[57] See www.PrivacyChoice.org for its list of known online consumer tracking companies.

[58] New Release, Better Business Bureau, BBBOnLine Privacy Program Created to Enhance User Trust on the Internet (June 22, 1998), http://www.bbb.org/us/article/bbbonline-privacy-program-created-to-enhance-user-trust- on-the-internet-163 (last visited 2/10/11).

[59] Id.

[60] The earliest web presence for the BBB Online Privacy Program appears at the end of 2000. http://web.archive.org/web/20010119180300/www.bbbonline.org/privacy (last visited 2/10/11).

[61] http://web.archive.org/web/20010201170700/http://www.bbbonline.org/privacy/how.asp (last visited 2/10/11).

[62] http://web.archive.org/web/20030407011013/www.bbbonline.org/privacy/dr.pdf (last visited 2/10/11).

[63] See, e.g., http://web.archive.org/web/20070124235138/www.bbbonline.org/privacy/dr/2005q3.asp (last visited 2/10/11). While the BBBOnline privacy program dispute procedures were better and more transparent than other comparable procedures, the BBBOnline dispute resultion service was controversial in various ways. In 2000, for example, questions were raised when the BBBOnline Privacy Program, under pressure from the subject of a complaint, vacated an earlier decision and substituted a decision more favorable to the complaint subject.

[64] Federal Trade Commission, Privacy Online: Fair Information Practices in ihe Electronic Marketplace, A Report To Congress 6 (2000), http://www.ftc.gov/reports/privacy2000/privacy2000.pdf. (last visited 2/10/11).

[65] http://web.archive.org/web/20070830164536rn_1/www.bbbonline.org/privacy (last visited 2/10/11).

[66] http://www.bbb.org/us/european-union-dispute-resolution (last visited 2/10/11). It is not clear if BBBOnline has actually handled any US-EU Safe Harbor complaints.

[67] See, e.g., the Equifax Online Privacy Policy & Fair Information Principles, https://www.worldprivacyforum.org/pdf/equifaxprivacypolicydec5.pdf (last visited 2/10/11); Good Feet, http://goodfeet.com/about-us/privacy-policy (last visited 2/10/11).